February 2012

When Four White Unionists Died

Defending Their Black Comrades

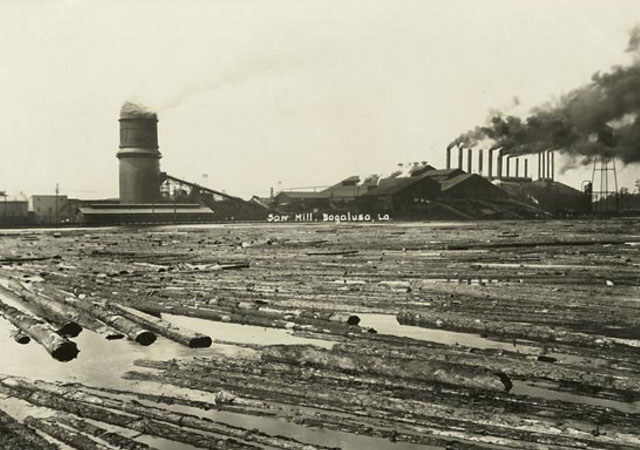

Great Southern lumber mill in Bogalusa, Louisiana, the largest in the world at the time, saw black and

white workers fighting together for their rights against racist capitalists. (Photo: New York Public Library)

In the night of 21 November 1919, a mob of Great Southern Lumber company gunman and Klan-type vigilantes organized in a “Self-Preservation and Loyalty League” (SPLL) showed up at the home of Sol Dacus, the head of the black section of the International Union of Timber Workers in Bogalusa, Louisiana. The gunmen riddled his house with bullets, narrowly missing both Dacus and his wife and children. This assault set the stage for the climax in a long struggle by two American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions to organize what was then the largest sawmill in the world.

Evading the posse, Dacus showed up in town the next day. The sight was so extraordinary that it made the national news. The New York Times (23 November1919) reported: “This morning, to the surprise of the Loyalty League men, the Negro they sought emerged from his hiding-place and walked boldly down the principal street of the town. On either side of him was an armed white man.....” Dacus was flanked by J. P. Bouchillon and Stanley O’Rourke, two white unionists, who had volunteered to accompany him to union headquarters, toting shot guns.

This action was so threatening that the Great Southern blew the mill’s siren whistle – the “riot” signal – in order to remobilize its posse and simultaneously secured an arrest warrant against O’Rourke and Bouchillon for “disturbing the peace.” That was easy enough, considering that Great Southern’s General Manager Sullivan was also the mayor of this nakedly company town. The company also maintained the largest private army in Louisiana.

A horde of gun thugs and SPLL men converged on the union offices, located in the auto repair shop run by Central Trades and Labor Council President Lem Williams. According to the company version, which was duly parroted by the Times, a small group of seven men in the office opened fire on the 150 “deputies.” Far more credible is the account by Louisiana AFL President Frank Morrison in a 4 February 1920 letter to the NAACP:

“They drove up in their automobiles and without warning began to shoot. Williams was the first to appear at the door where he was shot dead, without a word being spoken by either side. Two other men, who were in his office at the time, were shot down, and the bodies of the three men fell one on top of the other in the doorway. The other men attempted to leave the building by the back door where two of them were shot down while coming out with their hands above their heads; the only shot fired by any man connected with the labor people in any way was fired by a young brother of Lum Williams who shot Captain LeBlanc in the shoulder with a .22-caliber rifle, after he had shot his brother to death. This Captain LeBlanc was a returned soldier and was placed in command of the gunmen in Bogalusa.”

Williams, Bouchillon and another union carpenter, Thomas Gaines, were killed immediately. O’Rourke, severely wounded, was taken to the company hospital and held incommunicado until he died. But Dacus again slipped through their hands and fled to New Orleans, where he was rejoined by his family.

In a January 1920 article in the leftist review The Liberator NAACP board member and socialist Mary White Ovington pointed out, “The black man had dared to organize in a district where organization meant at the least exile, at the most death by lynching.” She added, “Not since the days of Populism has the South seen so dramatic an espousal by the white man of the black man’s cause.” Three-quarters of a century later, historian Stephen Norwood wrote: “The gun battle in Bogalusa, when white union men took up arms and gave their lives to defend their black comrade, represents probably the most dramatic display of interracial labor solidarity in the Deep South during the first half of the twentieth century” (“Bogalusa Burning: The War Against Biracial Unionism in the Deep South,” Journal of Southern History, August 1997).

Race-Baiting and Repression in the Service of Union-Busting

The struggle at Bogalusa took place against a backdrop of a long history of attempts at interracial working class solidarity in Louisiana ranging from the Knights of Labor in the sugar fields and sawmills to New Orleans longshore. The efforts by the Knights of Labor were essentially drowned in blood, such as in the Thibodaux Massacre of November 1887, in which as many as 300 striking black sugar plantation are estimated to have been killed. A new wave of class struggle, however, was launched by the Brotherhood of Timber Workers (BTW) in the lumber industry of western Louisiana and Texas in 1911-1913.

Mass meeting of Brotherhood of

Timber Workers in De Ridder, Louisiana

on 1 August 1911. BTW enrolled black

workers and affiliated to the

syndicalist Industrial Workers of the

World.

Mass meeting of Brotherhood of

Timber Workers in De Ridder, Louisiana

on 1 August 1911. BTW enrolled black

workers and affiliated to the

syndicalist Industrial Workers of the

World.

In the bitter Louisiana-Texas “lumber war,” the capitalists immediately resorted to race-baiting as well as repression. AFL unions usually bowed to Jim Crow and set up segregated locals when they attempted to organize black workers at all, which is usually referred to as “biracial” by historians. But the BTW began to challenge these taboos. “Big Bill” Haywood from the Industrial Workers of the World recalled that when he attended a BTW gathering in May 1912 he was surprised not to see any black faces and was told they were all sitting in another room. He replied:

“You work in the same mills together. Sometimes a black man and a white man chop down the same tree together. You are meeting in convention now to discuss the conditions under which you labor. This can’t be done intelligently by passing resolutions here and then sending them out to another room for the black man to act upon. Why not be sensible about this and call the Negroes into this convention? If it is against the law, this is one time when the law should be broken.”

–Bill Haywood’s Book (1929)

The blacks then joined the assembly, which also voted that the BTW affiliate to the IWW.

Over the next two years, the BTW was essentially defeated by the bosses' superior firepower rather than by any racial divisions. The lumber companies' Burns and Pinkerton gun thugs, supplemented by middle-class vigilantes, raided union meetings, whipped BTW members and expelled union members and their families from their homes. This culminated in a shoot-out at Grabow, Louisiana in July 1912 when the private army of the Galloway Lumber Company assaulted a union meeting. Three workers and a company thug were killed. More than 50 BTW members were then tried for conspiracy and murder, and eventually acquitted. The final confrontation took place in Merryville, Louisiana in early 1913 when the American Lumber Company fired a number of white unionists. Black workers struck in solidarity; here as well interracial solidarity remained solid. But the strikers were driven out of town en masse.

By 1919, when the AFL tried its hand, it expected more success. Virulently patriotic, it had benefited from a certain benevolent neutrality on the part of the Woodrow Wilson administration during World War I and boosted its membership rolls. But this was reversed at the war’s end, and never really applied to the South anyway. So when the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (UBC) and the International Union of Timber Workers (IUTW) tried to organize Bogalusa, they got the IWW treatment. (Bogalusa Story, the official history of the town and a nauseating paean to the Great Southern, blames the “troubles”… on the IWW.) While the industrially organized BTW had also gone down to defeat, the craft set-up of the AFL, on top of having segregated locals, further divided the workers.

Bogalusa, located in Washington Parish in eastern Louisiana on the Mississippi state line, was founded in 1906 by northern investors. It was supposed to be a model of company paternalism, with better housing, sports programs and a host of other amenities – the “New South City of Destiny.” Transplanted New Yorkers like company manager Sullivan grotesquely aped the “generosity” of Old South plantation owners by distributing little gifts to “deserving” workers. But this all held only as long as you did as you were told. When wages failed to keep pace with inflation and workers began to get interested in unionizing, the company initially attempted to fire pro-union white workers and recruit black scabs. When this failed, it brought out the armed fist. The mill was surrounded with barbed wire and machine guns.

The company also resorted to that old Southern standby, forced labor. As Louisiana AFL president Morrison reported:

“They have been continually arresting Negroes for vagrancy and placing them in the city jail. It seems that a raid is made each night in the section of the town where the Negroes live and all that can be found are rounded up and placed in jail charged with vagrancy. In the morning the employment manager of the Great Southern Lumber Company goes to the jail and takes them before the city court where they are fined as vagrants and turned over to the lumber company under the guard of the gunmen where they are made to work out this fine. There is now an old Negro in the hospital at New Orleans whom they went to see one night, and ordered to be at the mill at work next day. The old man was not able to work, and was also sick at the time. They went back the next night and beat the old man almost to death and broke both of his arms between the wrist and elbow.”

In addition to whipping up a red scare (including the absurd claim that the organizing drive was financed by Moscow), the company played the race card, circulating a photo of an IUTW meeting in Mississippi in which whites and blacks (including Dacus) could be seen together. The bosses whipped up hysteria over “race mixing” hoping to undermine white workers’ commitment to the struggle. The AFL craft unions were much less inclined than the BTW to challenge any aspect of Jim Crow. The union leadership initially offered not to seek to organize black workers if the company promised not to use them as scabs. Yet the AFL also demanded equal wages for white and black, and was now nonetheless locked into a desperate, life-or-death struggle with the lumber trust. And once in it for good, they went to the limit in defending their black co-workers.

Bogalusa Burning: The Battle Comes

to a Head

Murders in Bogalusa

were national news. Above left: gunmen of

the Great Southern Lumber

Company. Right: New York Times (23

November 1919) report the day after

killings.

1919 saw a tremendous upsurge in

the class struggle in the United States,

with a strike wave that extended even to

Southern cities. It is estimated that

one-fifth of all U.S. workers went on strike

that year. At the same time, postwar layoffs

pitted white against black and led to a

series of racist pogroms (mob attacks)

against black workers in many cities,

including Chicago and Omaha. But there was

also resistance by labor to the bosses’ use

of racist threats and demagogy to under

workers struggle. In Bogalusa, when Great

Southern threatened to bust up a black union

meeting scheduled for 14 June 1919, nearly

one hundred white unionists marched into the

black neighborhood armed with rifles and

shotguns and escorted black residents to the

meeting. The IUTW signed up 462 new black

members that night.

At the same time, according to a

report in the Everett. Washington Labor

Journal (11 July 1919), more than 200

black workers were forced to leave Bogalusa,

and residents reported that a black man was

beaten so badly in jail that he died in

Charity Hospital in New Orleans shortly

afterwards. On the eve of Labor Day there

was another racist provocation. A mob of a

thousand white men lynched a black war

veteran on the usual accusation of

supposedly trying to rape a white woman and

dragged his body behind an auto through the

black quarter. Yet the next day 800 blacks

and 1,700 whites marched through the city

together in a pro-union demonstration. The

terror continued, but by September 23, when

the company resorted to a lock-out, 95% of

the plant had been organized.

Meanwhile, around the country, the upsurge of labor struggle was met with the government’s postwar “red scare.” On November 1, the United Mine Workers under John L. Lewis struck in defiance of injunction issued under a wartime strike ban. The coal operators charged that the walkout was ordered and financed by Lenin and Trotsky in Moscow. The press spoke of the strike as “insurrection” and “Bolshevik revolution.” In the Pacific Northwest on November 11, the Centralia, Washington massacre took place as American Legionnaires in an Armistice Day parade stormed the local IWW union hall. Less than two weeks later came the attempt to murder Sol Dacus and the November 22 Bogalusa massacre.

In response to

the killing of the Carpenters union men, the

Louisiana AFL requested that federal troops

be brought in. But when the troops arrived

the following day, they proved solidly

pro-company. Declaring that “most all” the

workers were “loyal to the Company and want

to go back to work,” the commanding officer

offered to have dinner with the company

director, adding: “Perhaps we can play some

bridge.” Meanwhile, lynch mob terror reigned

in Bogalusa as union members were being

fired and run out of town. None of the

lynchers were of course ever prosecuted.

The massacre had had the expected chilling effect: neither the state AFL (which still had significant strength on the New Orleans docks) nor the national AFL took any other action than supporting the victims' families in civil suits. State and federal courts inevitably ruled in favor of the company. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned a lower court’s award of $30,000 to Lem Williams' widow, ruling that the racist mob had been a legitimate police force. The moment of interracial class solidarity passed. By 1939, the timber was gone and Great Southern had sold off its holdings. All that was left in the town was a paper mill in which the AFL International Brotherhood of Pulp, Paper and Sulphite Workers gained recognition without challenging Jim Crow in any way.

Honor the Heroes of Bogalusa 1919

But Bogalusa 1919 had sown some seeds, here and there. The Messenger, a black socialist review based in New York, had publicized the case, underlining the potential for united class struggle that Bogalusa had offered. If its editors Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen soon reneged on their initially pro-Bolshevik sympathies, others around the magazine, such as Lovett Fort-Whiteman and Grace Campbell, made the leap to become the first black Communists. In Cuba, the revolutionary Carlos Baliño, a founding member of the Communist Party there, picked up on The Messenger report to talk about Bogalusa example in the journal Espartaco (see www.walterlippmann.com/carlosbalino.html). By the early 1930s, the U.S. Communist Party, despite its Stalinist deformations, was the only group still recalling the Bogalusa massacre as it launched an audacious interracial organizing drive in the Deep South which defied Jim Crow.

Charles Sims of the Deacons for

Defense and Justice in Bogalusa stands

defiantly on courthouse steps holding

Klan hoods. (Photo: Bettman/Corbis)

Charles Sims of the Deacons for

Defense and Justice in Bogalusa stands

defiantly on courthouse steps holding

Klan hoods. (Photo: Bettman/Corbis)

Fast forward to the mid-1960s and Bogalusa was the site of one of the first organized campaigns of armed black self-defense in the South. Lance Hill of the Southern Institute of Education and Research, points to the 1919 union struggle in his history, The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement (University of North Carolina Press, 2004): “Although Great Southern had defeated the union threat, management lived in perpetual fear of a worker uprising; at one point the mill manager built a secret escape tunnel in the basement of his home. It was on this bloody terrain that the Deacons would take root and lead one of the most remarkable and successful local campaigns of the civil rights movement.”

For more than a century, the defenders of the Confederacy have blanketed the region with monuments to its “cause” and named public buildings after slaveholders and other racists. This began to change after the civil rights movement. In the early 1990s, New Orleans schools began removing the names of Confederate generals and slave-owning governors. Yet even the liberal New York Times (12 November 1997) fretted when George Washington Elementary School in New Orleans was renamed in honor of black surgeon Dr. Charles Richard Drew. The removal of the name of the slave-owning first U.S. president “raised questions about whether efforts to broaden history” might have been “taken too far.”

Or not far enough. In our view, there ought to be schools in Louisiana named after Sol Dacus, Lem Williams, Bouchillon and O'Rourke. And Charles Deslondes, the leader of the 1811 slave revolt, for that matter. It's a shame as well that the Carpenters union didn't see fit to authorize a monument to its own martyred members at its 2005 convention, although the paper of the Portland, Oregon UBC Industrial Council, Union Register (Wnter 2011) published an article about it last year. But what would really honor the heroes of Bogalusa 1919 would be a drive to smash racial oppression in the South once and for all. As we wrote a decade ago (The Internationalist No. 10 (June 2001) of the Charleston Five, black longshoremen in South Carolina threatened with years in prison for defending their union:

“Labor cannot unionize the South unless it sets its sights on rooting out the bloody legacy of the Confederacy, and that is a revolutionary struggle in the most literal sense. At the same time the need for workers internationalism is highlighted by the growing presence of immigrant workers, many of them “undocumented,” in Southern industries and businesses. The Kluxers’ brand of nativist fascism has always fed off ‘America-firstism’ and xenophobia; the same lynch-rope terrorists who target black people and unionists go after immigrant workers with a vengeance. Labor must fight for full citizenship rights for all immigrants, who from one coast to the other have played a dynamic role in recent union drives among the most exploited sections of the U.S. proletariat, many of them women workers.

“What all these tasks demand is to break from the Democrats and wage a class struggle against all capitalist parties (including Nader’s red-white-and-blue Greens), forging a revolutionary workers party that fights for black liberation through socialist revolution. Against those who preached the pipe dream of overcoming slavery through conciliation with the master class, the great Frederick Douglass insisted: ‘Without struggle there is no progress.’ Today the road to freedom for capitalism’s wage slaves in racist America is that of intransigent revolutionary struggle, together with workers the world over, to take society’s wealth and resources out of the hands of the exploiting few and put them in the service of the working people.” ■

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com