June 2013

Against Bolivian General Strike

Police attack striking workers in La Paz, May 18. (Photo: EFE)

JUNE 6 – In a Latin American capital, thousands of impoverished workers wage a general strike, facing off against riot police, as the streets are enveloped in tear gas. As the government carries out mass arrests, strikers denounce it as an instrument of capital and enemy of the working class. From the presidential palace, a witch hunt is launched denouncing the strike as a sinister leftist conspiracy and government supporters mobilize to “defend democracy” against the workers. The scenario is not a new one, but in this case the regime in question has been lionized by the “anti-neoliberal left” worldwide.

The country is Bolivia and the government that of President Evo Morales and Vice President Álvaro García Linera, leaders of the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS – Movement Towards Socialism), who claim to be leading a “cultural and democratic revolution.” On May 6, the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB) labor federation launched the most important workers’ mobilization since Morales’ 2005 election as the first indigenous president of South America’s poorest nation. One of the sharpest class conflicts of recent years, the confrontation highlights the stark fact that the “Indianist” capitalist regime is counterposed to the basic needs and hard-won rights of the country’s indigenous worker and peasant majority.

Militant miners spearheaded the general strike together with factory, health, education and other workers, demanding “retirement with dignity” in a country where miners have long been more likely to die by the age of 40 than to have any chance of a decent retirement. As the miners’ traditional dynamite blasts punctuated union slogans in the streets of La Paz, Oruro and Potosí, strikers denounced Morales for maintaining the basic features of the anti-worker pension scheme inherited from despised former president “Goni,” Washington’s rightist favorite Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada who was overthrown in the “Gas War” that swept the altiplano a decade ago. Miners’ wives played a prominent role in building road blockades, as the workers’ protest cut traffic at 40 key roads and highways.

A Class Mobilization

Against Hunger and Repression

(Above) Miners

from Huanuni, the largest mine in Bolivia,

respond to police attack by dynamiting

bridge at Caihuasi, May 8. (Below) Evo

Morales’ police pursue strikers into the

hills, arresting 337.

(Fotos: Kyrios; Radio Nacional de Huanuni;

Víctor Guitiérrez/La Razón)

Desperate to break the

strike, the Morales government launched a

barrage of repressive measures, arresting 400

unionists (in some cases demanding prison

terms of up to six years), decreeing house

arrest against leaders of the Oruro regional

labor federation and mobilizing a media

campaign to smear unionists as tools of the

right. On May 17, Morales declared the strike

“illegal.” Faced with violent repression from

the same police and armed forces that have

stained the altiplano with miners’ blood time

and again for a century, the workers of

Huanuni – Bolivia’s largest mine – reportedly

seized three policemen, holding them inside a

mineshaft to exchange them for arrested

unionists.

Desperate to break the

strike, the Morales government launched a

barrage of repressive measures, arresting 400

unionists (in some cases demanding prison

terms of up to six years), decreeing house

arrest against leaders of the Oruro regional

labor federation and mobilizing a media

campaign to smear unionists as tools of the

right. On May 17, Morales declared the strike

“illegal.” Faced with violent repression from

the same police and armed forces that have

stained the altiplano with miners’ blood time

and again for a century, the workers of

Huanuni – Bolivia’s largest mine – reportedly

seized three policemen, holding them inside a

mineshaft to exchange them for arrested

unionists.

During a particularly savage police attack on May 8, against Huanuni miners on the highway between Oruro and Cochabamba, Oruro labor federation leader Juan Carlos Guarachi told the Cadena A television network in a phone interview: “All of us miners are here in the hills still facing off against the police, while with the fury and rage of the workers the bridge from Caihuasi towards Caracollo has been blown up.” He continued: “Yet again the government is acting like neoliberal governments do, yet again with disdain and the incapacity of all of its ministers, who refuse to meet the workers’ demands.”

For his part, Huanuni union leader Ronald Colque denounced the MAS for carrying out “repression in the purest style of neoliberal governments” (ANF, 17 May). This accurate observation is a bitter one for large numbers of workers and poor peasants who had placed their hopes in the MAS, which came to power with torrents of rhetoric against neoliberal economics, which (like the rest of the populist and nationalist “left”) it denounced while upholding the system of capitalist exploitation. Not only miners were attacked. Photos appeared in the Bolivian press showing factory workers injured when the police fired shots against them as they were carrying out a roadblock at the town of Pacotani, in the Department of La Paz.

In a particularly cynical operation, the MAS called a May 23 anti-strike rally “in defense of democracy,” bringing out government-aligned peasant and neighborhood associations to denounce the workers. In his speech there, Morales declaimed: “If there is no unity of the Bolivian people, then it’s not possible to consolidate the efforts of [government] authorities and leaders in order to guarantee this democratic cultural revolution.” He went on to stress his regime’s links to the “revolutionary processes in...Ecuador, Argentina, Brazil,” where other presidents of Latin America’s “pink tide” combine capitalist economics with populist/nationalist rhetoric.

In Bolivia, a country where decades of convulsive class struggles produced a particularly strong historical consciousness, the parallel to Morales’ populist/nationalist predecessors was clear. Using sectors of the peasantry beholden to the ruling party as a battering ram against the miners and other proletarian sectors was a hallmark of the MNR, the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement brought to power in the 1952 revolution. When the army rebuilt by the MNR overthrew it in the Washington-backed coup of 1964, junta head René Barrientos forged a “Military/Peasant Bloc” aimed explicitly against mine unionists, student and teacher radicals, and other “subversive elements.”

Grim Realities of

Morales’ “Andean Capitalism”

They’re back. March

of combative Huanuni miners arrives at

the capital, La Paz, May 20.

(Photo: AFP)

During the “lost decade” of the 1990s, governments across Latin America following the free market policies dictated by Washington and Wall Street devastated workers’ living standards. Since the turn of the century, a series of populist bourgeois governments have come into office spouting leftist rhetoric while still repressing workers. Hugo Chávez (and his successor Nicolás Maduro) in Venezuela claimed to be building “21st century socialism,” but Bolivia’s leaders were more forthright. Campaigning for the 2005 election, García Linera called for “a kind of Andean capitalism” (Econoticias Bolivia, 1 September 2005). And in an article in Le Monde Diplomatique (January 2006), the vice president declared a “new economic model” which he dubbed “Andean-Amazonian capitalism.” The May 2013 general strike shows what this means.

“The COB Strike Highlights Political Polarization in Bolivia,” headlined the liberal Otramérica site (17 May). The strike is far from the first time the Morales government has faced off against organized labor or sectors of its base among peasants, the urban poor and middle class (see “Bolivia: Evo Morales Against the Workers and Oppressed,” The Internationalist, September 2007). Despite his origins as leader of coca-growing farmers, Morales has used the army to repress peasants in coca regions as well as Amazonian peoples who accused him of pandering to multinational companies with his plan to build the TIPNIS highway through an indigenous rainforest reserve.

Repeatedly clashing with the teachers and other dissident union sectors from the first years of his administration, Morales faced factory workers’ strikes and marches in 2010 when he capped wage raises at 5 percent and maintained a poverty-level minimum wage. At the end of that year he slashed fuel subsidies desperately needed by the urban and rural poor. Angry protests forced reversal of this move, whose similarity to austerity measures typically demanded by the International Monetary Fund was noted even by sympathetic observers. Yet as some of Morales’ North American enthusiasts noted earlier this year: “Exports are up, and Bolivia’s international monetary reserves reached a new $14 billion high” (People’s World, 14 January).

The May 2013 general strike brought class confrontation to its sharpest point so far under the MAS regime, in a struggle where miners and other working-class sectors indisputably played the central, leading role.

When it comes to continuities between the “Andean capitalism” of Morales and García Linera and the “Washington consensus” embraced by their right-wing predecessors, the question of workers’ pensions is both illustrative and deeply felt by the country’s working class. The privatization mania that swept Latin America put “defined benefit” pensions under the gun as early as 1980. In Chile, dictator Augusto Pinochet – advised by Milton Friedman’s free-marketeering Chicago Boys – turned pension plans over to private investment funds seeking new troughs for financial speculation. Mexico followed suit in the late ’90s, when Yale grad President Ernesto Zedillo imposed the AFORE system of privatized pensions.

In Bolivia, during his first term in the Palacio Quemado, Harvard Boy “Goni” Sánchez de Lozada privatized pensions in 1996, establishing a new system “based on individual capitalization accounts” in line with the “capitalization” (privatization) of virtually all nationalized enterprises (World Bank, The Bolivian Pension Reform, July 1997). Three years ago, Evo Morales carried out a new pension reform, lowering the retirement age but maintaining a situation in which making it to retirement age with even a minimal chance of escaping destitution remains an impossible dream for the vast majority.

As noted at the time by Bolivia’s Center for the Study of Labor and Agrarian Development, Morales’ pension law represented “the continuity of neoliberal policy,” not only “maintaining the individual capitalization system that neoliberalism imposed” (employers make little or no contribution) but deepening “reliance on the efforts of the wage workers themselves, whom it treats as a privileged sector.” Morales’ law promised the military and police retirement at a 100 percent pay rate, while workers were told years of contributions would (supposedly) bring them retirement at 70 percent of normal pay (CEDLA, Nueva Ley de Pensiones, December 2010).

During last month’s general strike, CEDLA released a new study demonstrating that “the present pension system does not ensure a decent retirement income that would allow workers to cover their basic necessities when they go into retirement, and when their physical strength and labor market conditions do not allow them to go on working.” Morales’ 2010 “reform” had the effect of “leveling pensions downwards” so that even a worker who somehow managed to maintain steady contributions for 30 years would still live in dire poverty. This in a country where the monthly minimum wage is US$116, male life expectancy is 65 years, and miners have long faced the prospect of dying from silicosis before they could ever retire.

Strikers denounced “the government’s lies about Huanuni,” refuting with facts and figures the demagogic accusation that the Huanuni mine – which is part of the COMIBOL government mining company – is supposedly a drain on the national economy and that its 4,800 workers are some kind of privileged sector. The miners stressed that under Morales’ pension law, a miner would need to make steady contributions for 35 years in order to get a pension equivalent to US$535 a month. Meanwhile, mineshafts lack basic “ventilation conditions...causing continual deaths of young workers,” so that an estimated 20 percent are already “suffering from silicosis and [other] lung diseases” (Huanuni Miners Radio communiqués, 14 May).

With the grim prospect of dying in poverty facing millions of Bolivian workers and peasants, as well as impoverished sectors of the middle class, the COB’s demand for “retirement with dignity” struck a real chord. The national miners union (FSTMB) began the strike with the demand for a pension equal to the average wage of a working miner (100% pension). Faced with the government’s intransigence and repressive onslaught – and in the absence of elected strike committees able to debate and decide such fundamental questions – the union leadership cut the demand back to 70 percent. On May 22, the COB “suspended” the strike, tentatively accepting a deal to reduce the number of years miners have to work to qualify for retirement, with other details unclear.

While leaders said the labor federation would remain on “emergency footing” during a 30-day period in order to evaluate the proposed accord, a number of union sectors expressed strong opposition to the decision to demobilize the workers and halt the strike.

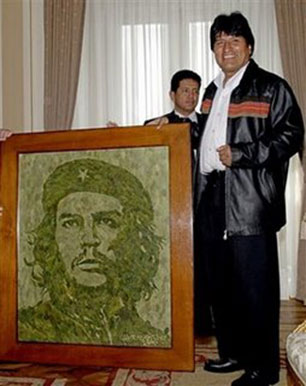

Evo Morales and the Left

Bolivian

president Evo Morales demagogically

poses as leftist while repressing

striking workers. Right:

with an iconic

portrait of Ernesto Che

Guevara made of coca leaves,

in 2006. (Photo:

Reuters)

Bolivian

president Evo Morales demagogically

poses as leftist while repressing

striking workers. Right:

with an iconic

portrait of Ernesto Che

Guevara made of coca leaves,

in 2006. (Photo:

Reuters)

Dazzled by the “Evo phenomenon,” many purported leftists have pretended that a specifically proletarian perspective for Bolivia – a country historically known for some of the sharpest class struggles in the hemisphere – was effectively superseded by the election of an indigenous president, the “unity of the people,” “new communitarian forms of politics,” etc. Reflecting the same bourgeois impressionism while adding a dash of pseudo-Marxist verbiage, the Spartacist League, as part of its descent into a U.S.-centric and idiosyncratic left centrism, went so far as to claim that the Bolivian working class ceased to exist (see “Spartacist League Disappears the Bolivian Proletariat,” The Internationalist No. 24, Summer 2006).

These claims echoed the self-justifications of a regime whose main success has been to put a new face on the old function of the bourgeois state apparatus: defending capitalist property relations against the workers, poor peasants and impoverished urban population. That the MAS runs a capitalist regime has never been a secret (except to those willfully blinded by their own illusions): Morales and García Linera have ruled for almost eight years now under the banner of what they call “Andean capitalism.”

As we wrote immediately after the December 2005 vote that brought the MAS to power, “Morales’ election certainly reflects the urgent hope of fundamental social change among the oppressed majority,” as the election of the continent’s first indigenous president “has generated great expectations among the masses excluded from power by the k’ara (‘white’) elite.” All the more so was it the responsibility of Marxists to tell the fundamental truth that the Morales government would use this prestige to refurbish the capitalist state for more effective use against the indigenous toilers that voted it into office. As we noted:

“MAS theoretician García Linera stresses that the MAS will build a ‘center-left’ government. Underlining his slogan of ‘Andean capitalism,’ he says it will be ‘linked to global markets’ and ‘entrepreneurial sectors,’ which could last 40, 60 or even 100 years. The slogan is utopian/reactionary in its appeal to an imaginary ‘national’ form of class exploitation. However, its actual content is to give a more ‘Andean’ face to semi-colonial Bolivia’s subordination to real, international capitalism (imperialism)....The bourgeois Morales regime does not merit the slightest confidence from the workers and peasants.”

–“Bolivian Elections: Evo Morales Tries to Straddle an Abyss” (December 2005), reprinted in The Internationalist No. 23, April-May 2006

Vindicated anew by last month’s general strike, the perspective of revolutionary proletarian struggle in Bolivia calls out for a leadership forged on Leon Trotsky’s program of permanent revolution, in which the working class at the head of the poor peasantry and other oppressed sectors resolves democratic tasks by taking power and passing over to socialist measures. The country has a long tradition of struggle by militants identified with Trotskyism, many of them characterized by exemplary courage and dedication. The tragedy of Bolivia’s revolutionary movement is its decades-old adaptation to the labor bureaucracy and bourgeois nationalism, going back even before the 1952 revolution (see S. Sándor John, Bolivia’s Radical Tradition: Permanent Revolution in the Andes [University of Arizona Press, 2009).

The main organization identified with Trotskyism in Bolivia is the Partido Obrero Revolucionario (POR – Revolutionary Workers Party). Led by Guillermo Lora until his death in 2009, the POR heads the La Paz teachers union. In the mass upheavals preceding Morales’ election, the POR played a thoroughly centrist role, helping provide a left cover to the labor bureaucracy and neighborhood association leaders who derailed the Gas War uprisings of 2003 and 2005, paving the way for the “Andean capitalist” regime. Seconding them in this task was the smaller LORCI (Revolutionary Workers League), which is part of the Trotskyist Faction led by the Argentine Partido de Trabajadores por el Socialismo.

La Paz teachers union, led

by the POR, at May 8

march.

La Paz teachers union, led

by the POR, at May 8

march.

(Photo: Agencia de Noticias Fides)

During the May 2013 general strike, the POR’s weekly Masas repeatedly combined vivid reports of police repression with fervid calls on the very same police to “join the people’s struggle.” Thus Masas (17 May) reported that a planned mass protest at the international airport in Santa Cruz was met by the “caveman-reactionary assault of the riot police,” who savagely beat “older women teacher compañeras.” The police association had warned it would organize actions unless its demands (including overtime pay, presumably for occasions when beating and gassing elderly teachers goes beyond the usual workday) were met within a month’s time. A POR appeal reprinted in the same issue called: “POLICE: Don’t wait for the month-long period to end. Start now!”

Demagogically, the MAS seized on such appeals to escalate its McCarthyite smears against the left, accusing the POR of seeking a “coup” against the government. The real danger of pretending that police are “workers in uniform” is to the working class and oppressed. “Uniting” with the repressive forces of the bourgeois state means setting the masses up for one bloody defeat after another. The POR’s policy goes back decades, to its call for “Bolivianization of the armed forces” and the Revolutionary Anti-Imperialist Front (FRA) it formed with deposed president General Juan José Torres in 1971.

To this day, the POR upholds the FRA as a model for class struggle in Latin America, together with the Asamblea Popular (People’s Assembly) that preceded it – an impotent conclave in which the POR and pro-Moscow Communist Party provided left cover to Torres’s labor lieutenants in the COB bureaucracy as they disarmed the working class politically and militarily in the face of General Hugo Banzer’s bloody military takeover.

In 2005, during the mass upsurge that overthrew Sánchez de Lozada’s successor as president, Carlos Meza, the POR and the LORCI were both instrumental in cobbling together an attempted reedition of the People’s Assembly in El Alto, the sprawling plebeian city in the altiplano above La Paz, where bureaucrats and populist leaders talked revolution only to demobilize mass protest at the decisive moment (see “El Alto and the ‘People’s Assembly’,” The Internationalist No. 21, Summer 2005). A certain symbiosis may be detected in the relation between the two avowed Trotskyist groups. The LORCI helps perpetuate the POR’s mythology about the 1971 Asamblea Popular but criticizes the FRA as well as the POR’s support to police “strikes” (while seeking to whitewash away its own capitulation to the February 2003 mutiny by the police).

For its, part, the POR scores the LORCI because it echoed Evo Morales’ calls for a constituent assembly, and for tailing the COB bureaucracy in discussions about setting up a purported labor party (PT–Partido de los Trabajadores), while baiting the LORCI in chauvinist vocabulary as “reformist good-for-nothings who came from abroad and claim to be Trotskyists” (Masas, 31 May). A first congress of the PT was held last March in Huanuni, with 1,300 delegates. While this reflected growing disillusionment with Morales’ MAS and anger at its anti-labor policies, the union bureaucracy headed by COB General Secretary Juan Carlos Trujillo has done its best to keep the PT safely within the limits of electoral reformism, intending no doubt to use it as a mere pressure group on the MAS.

For years now the LORCI has been calling for the formation of a “Political Instrument of the Workers,” or IPT, echoing COB leaders’ similar call. To be sure, they say that an IPT should embody class independence. For any genuine Trotskyist this means fighting for a revolutionary program, but the LORCI’s own agitation before, during and after the May strike has centered largely on classic reformist calls to “make the rich pay.” In an article on the looming strike over pensions, it wrote: “The solution is simple: the pension funds must be rescued through a big increase in contributions from the bosses who benefit from our exploitation, through higher taxes on the rich, the multinational companies, the bankers and finance capital” (Palabra Obrera, May 2013).

Against such tax-the-rich nostrums, genuine Trotskyists point out that capitalism’s impoverishment of the workers and peasants can be overcome only through the expropriation of the capitalist class in a proletarian revolution. Some months ago, the LORCI asked whether the PT would be “an instrument of workers political organization or a ‘party of the bureaucrats’” (24 January article on LORCI website). As the LORCI itself admits, the COB leaders relegated the PT to silence during this year's May Day demonstrations, and the supposed political expression of the workers played no significant role during the recent general strike. But in any case, without a revolutionary political program it could only push a more “worker-friendly” populism.

When the MAS was agitating for a (bourgeois) “constituent assembly” during the worker-peasant upheavals of 2003 and 2005, the LORCI called for a constituent assembly, a “revolutionary” one of course. When COB leaders called for a “political instrument of the workers,” so did the LORCI, always trying to appear as the left wing of whatever popular movement is in vogue. The inveterate tailism of the LORCI (a trademark of the Fracción Trotskista as a whole), and its constant adaptation to the “movement unity” outlook which labor and reformist left leaderships use to push class collaboration, can be seen in the following issue of its paper:

“We must prepare ourselves, given the perspective of great social convulsions fueled by the world capitalist crisis, organizing the conscious forces of the anticapitalist struggle, both in the unions and in the student movement, to create forces close to [afines con] the working class and convoking the unity of all the social movements of the oppressed, popular movements, ecologists, feminists, to join together in a common cause to end this decadent system together with the working class in all countries.”

–Palabra Obrera, June 2013

All get together in one big “popular movement” is their watchword. It’s a program for defeat.

What’s needed instead to defeat the bourgeois populism of Morales and García Linera, to unite the workers and impoverished indigenous peasantry, is an intransigent struggle for a proletarian vanguard embodying Trotsky’s permanent revolution. Creating the nucleus of such a party is key as hard-fought class struggles begin to break through illusions in the latest nationalist regime that has sought to tame the rebellious altiplano. This is the indispensable element needed to lead the struggle forward to socialist revolution, in Bolivia and beyond.

In an extensive analysis of Morales’ first year and a half in power, we detailed how “in populist style, he used...symbolic gestures and rhetoric to dress up actions that serve the needs of the ruling class” – from bolstering “the institutionality of the armed forces” to conciliating the hard-line racist right in the country’s eastern provinces, decreeing a fake “nationalization” of gas and oil, mobilizing pro-government “social movements” to attack labor sectors critical of his regime, and carrying out an “agrarian reform” that actually strengthened landowners’ power. Underlining the perspective of the League for the Fourth International, we wrote, and we repeat today:

“A worker-peasant-indigenous government is the only kind of regime in which the indigenous masses can actually seize and exercise power, undertaking their emancipation as part of an international socialist revolution....The raw material of revolutionary struggle is present in Latin America. That can be seen in many parts of the region, and it keeps cropping up in Bolivia....

“A revolutionary leadership is what’s required, and the real lessons of the Bolivian experience can help build it on the program of permanent revolution, with the willingness and determination to swim against the stream and fight for genuine communism in Latin America, here in the United States and everywhere.”

–“‘Andean Capitalism’ vs. Permanent Revolution – Bolivia: Evo Morales Against the Workers and Oppressed,” The Internationalist, September 2007 ■

Andean

capitalism and its

military guarantor. From

left: Bolivian vice

president Álvaro JUNE

6 – Meeting yearly in downtown

Manhattan, the Left Forum

(formerly Socialist Scholars

Conference, before it dropped

the inconvenient “s-word”) is

the premier meet-and-greet venue

for social democrats who want to

stay au

courant with the latest

fads and fashions in what passes

for left-wing (but not A decade later, they were gaga for Democrat Obama, while of course wanting to push him ever so slightly to the left. That got them the U.S. war on Libya, serial murder by drones from Afghanistan to Somalia, support for murderous Islamist “rebels” in Syria (the “moderates,” of course) and ever more intrusive police-state surveillance and racist repression “at home.” Workers’ wages continue to drop while hedge fund billionaires make out like bandits. In recent years, conference organizers looked to Latin America’s populist and popular-frontist “pink tide” for sustenance. At a 2008 round table on “new participatory movements” and “left governments” in Latin America, an Internationalist Group supporter met exasperation and incredulity when he pointed out that Bolivia’s Morales government was not in fact the path to indigenous liberation: for the oppressed indigenous majority to wield power, a socialist revolution led by the working class was required, a far cry from refurbishing the neocolonial bourgeois order with “Indianist” symbols and rhetoric. After he remarked that Bolivian miners’ battle cry “Volveremos” (We will return) was key to this revolutionary perspective, one superannuated social-democrat began to scream: “Don’t you get it? The Bolivian miners are gone, gone!” This was what such purported leftists hoped, but as this May’s general strike dramatically shows, the heroic miners of Bolivia are once again on the front lines of Latin America’s class struggle – and it was the capitalist government of Evo Morales that tried to break their strike. So now we come to the Left Forum of 2013, where the closing session’s featured speaker is none other than the ideologue of “Andean capitalism,” Morales’ vice president Álvaro García Linera. Just weeks ago he played a leading role in unleashing repression against the general strike of miners, factory workers, teachers and other labor sectors. Will García Linera repeat at the Left Forum his venomous denunciation of the workers as manipulated by “a small gang of Trotskyites...a handful of traitors to the people...seeking to repeat their reactionary rightist deeds” (El Deber, Santa Cruz [Bolivia], May 20)? When the occasion demands it, Left Forum habitués can mouth the words to the American miners’ song, “Which Side Are You On?” When it comes to South American miners in the forefront of actual class struggle today, forum organizers have given an unambiguous answer: on the side of Andean capitalism against the workers. The

Internationalist Group is

circulating a petition at the

conference calling on the

Bolivian government to end

repressive measures against

strikers, free all arrested

workers leaders and drop all

charges against them. Please

take a stand and add your

signature. Text

of petition circulated at Left

Forum below:

Call on Bolivian Government to End Repressive Measures Against Miners, Union Activists Arrested During May 2013 General Strike Last month (May 2013), miners, factory, health and education workers spearheaded a general strike called by the Bolivian Labor Federation (COB). The key issue in this strike in South America’s poorest country, where the monthly minimum wage is the equivalent of US$116, was the demand for “retirement with dignity.” Workers protested the pension system that they characterized as “the continuity of neoliberal policy” from the regime overthrown in the mass upsurge of 2003-05 which set the stage for the rise of the current Movement toward Socialism (MAS) government of Evo Morales and Álvaro García Linera. The pension issue is vital to the miners, many of whom suffer from silicosis and other lung diseases; Bolivian miners have long been more likely to die by the age of 40 than to have any chance of a decent retirement. During last month’s general strike, police repeatedly attacked, gassed and beat striking workers; some of the most intense attacks were against unionists from Huanuni, Bolivia’s largest mine, located in the department of Oruro. Of the approximately 400 strikers arrested during the general strike, dozens still face charges, medidas cautelares (preventive orders) and other repressive measures – among them Huanuni miners, most prominently Vladimir Rodríguez, secretary general of the COD (Departmental Labor Federation) of Oruro. As part of his prosecution, Rodríguez is under house arrest for six months under “preventive orders” forbidding him to participate in union affairs or even speak to the press. Join us in calling on the Bolivian government of Evo Morales and Álvaro García Linera to: Drop all charges, repressive and punitive measures against workers and unionists arrested during the general strike! |

| Activists

Demand: Stop Repression

Against Bolivian Miners!  Activistas en el

Left Forum en NY protestan

durante discurso del

vicepresidente boliviano,

Álvaro García Linera.

Reclamaban libertad y

anulación de cargos legales

contra trabajadores

huelguistas en Bolivia. (Foto: El

Internacionalista)

NEW YORK, June 9 – “Free Bolivian Miners, Drop the Charges” (against miners from Huanuni and other trade-unionists detained during last month’s general strike) was one of the slogans raised today durng the speech by Bolivian vice president Álvaro García Linera at the “Left Forum” held here. While the vice president presented “Nine Theses” on philosophical and political questions, left and labor activists –including several Latin American immigrants– held an attention-getting protest. They held up signs calling for freeing Vladímir Rodríguez, general secretary of the COB union federation in the department of Oruro, as well as other miners. During the protest – a united front initiated by the League for the Revolutionary Party and co-organized by the Internationalist Group – an open letter demanding an end to the repression was presented, signed by hundreds of conference participants. The Bolivian vice president did not respond. At the end of his speech, many in the audience called out asking that the issue be discussed, but instead the session was abruptly ended.

Among the slogans on the signs were “International Solidarity with Bolivian Workers,” “U.S. Imperialism, Hands Off Bolivia,” “Drop House Arrest and Charges Against Huanuni Miners and Other Trade-Unionists,” as well as expressions of solidarity with the indigenous peoples of the Tipnis area, and a call for “Bolivian Troops Out of Haiti!” A young immigrant worker in the protest commented at the end of the event: “We wanted to show our solidarity wth the heroic Bolivian miners, the peassants and the indigenous peoples against the repressive measures. Their struggle is that of the workers of the world.” |

Many

commented later that they used

to think that the government of

Evo Morales was left-wing, but

they were astounded by the

repression against strikers.

Many

commented later that they used

to think that the government of

Evo Morales was left-wing, but

they were astounded by the

repression against strikers.