September 2007

the Workers and Oppressed

Unionized miners at Huanuni defend themselves with dynamite against attack by government-backed

“cooperativistas,” 5 October 2006. Battle ended in victory for union workers. (Photo: Dado Galtieri/AP)

When

Evo Morales won Bolivia’s national

elections, becoming the first indigenous president in South American

history,

the international left almost unanimously hailed this as a victory for

the

oppressed. Yet as the League for the Fourth International (LFI) warned

before,

during and after the December 2005 elections, political support to

Morales’

regime of “Andean capitalism” is counterposed to the most fundamental

interests

of the workers, peasants and indigenous peoples. Below is an expanded

version

of the presentation by Abram Negrete at a forum of the Internationalist

Group

(U.S. section of the LFI) in New York City on May 7.

Evo Morales’ government in

Bolivia is now approaching a year and a half in power. Understanding

what this

government is and is not, what it has and has not done, is important

for

understanding the situation not only in Bolivia but in Latin America as

a

whole.

The Morales government has

posed again, in some cases very sharply, the questions of reform or

revolution

and the nature of social change in Latin America; the relation between

democratic issues and the class struggle; the question of how to fight

against

the oppression of indigenous peoples that goes back to the inception of

Spanish

colonialism in Latin America. It poses anew the question of how to

defeat and

uproot imperialist oppression, not just in Bolivia and the Andes, but

throughout

Latin America.

To put it another way, an

understanding of the situation in Bolivia and what the Evo Morales

government

represents raises all the questions addressed by Leon Trotsky’s program

of

permanent revolution, a phrase that is featured on the flyer for

today’s

program. That is, the conception that to resolve each of the issues

that I’ve

mentioned in favor of the oppressed, the working class must take power

at the

head of the poor peasantry and the exploited layers of the urban

population,

seizing the land and industries in a socialist

revolution, that in order to survive must extend itself throughout

Latin

America and into the United States, which is the dominant military,

political

and economic power in this hemisphere.

A History of Upheaval

One of the most interesting

things about Bolivia, and one of the reasons it’s important to look at

the

current situation, is that Bolivia has been a testing ground for the

validity

of just about every kind of political program in Latin America. This

includes

the oligarchic rule of the Liberal elite at the beginning of the 20th

century;

something called “military socialism” in the late ’30s, with its

different

flavors of populism; the classic populist regime that came to power in

1952

under the leadership of the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement

(MNR – Movimiento

Nacionalista Revolucionario); the guerrilla strategy of Che Guevara in

the

1960s; military dictatorships and civilian neoliberal regimes. And now

a

government that claims to represent a particularly “indigenist”

standpoint,

that is, one that supposedly uniquely reflects the interests and

outlook of the

indigenous masses. These are some of the different recipes for managing

Bolivian society that have been attempted.

In that sense, because of

the convulsiveness of Bolivian society, because of the sharpness with

which all

social issues are posed, it has also been a laboratory or testing

ground for

the validity of the conceptions of the permanent revolution posed first

by Leon

Trotsky in the context of the Russian revolutions of 1905, February

1917 and

October 1917. This revolutionary program stands opposed to all the

recipes for

tinkering with capitalism, from the “two-stage revolution” schemas

pushed by

Stalin to all the varieties of bourgeois nationalism, whether they

dress in a

three-piece suit or indigenous attire.

Bolivia is the poorest

country in South America and the second poorest in the hemisphere; only

Haiti

is poorer. By most calculations it is the most indigenous country in

Latin

America, with about 62 percent of the population referring to or

categorizing

itself as indigenous and most of the population speaking as its first

language

either Quechua, which was the language of the Incas, or Aymara, the

language of

some of the people who have lived in that region since before the Incas

conquered it, or Tupi-Guaraní, a complex of languages mainly in

the eastern

regions.

The indigenous population

includes the overwhelming majority of the peasantry and has been

historically

excluded and oppressed in the most brutal ways. During the heyday of

the old

regime in Bolivia before the revolution of 1952, if you picked up a

newspaper

and opened it on just about any day, you could see pictures of Indian

people in

chains being turned over to the authorities, with a caption about

“savages”

being imprisoned for infringing this or that regulation. Until the 1952

revolution, indigenous people were often not allowed to enter many of

the main

plazas and streets of La Paz and other cities.

From out of this indigenous

peasantry there arose a working class, centered on the tin miners. It

was – and

continues to be, despite premature announcements of its supposed demise

– one

of the most militant proletarian sectors in the hemisphere, which has

overthrown one government after another. Its political outlook has been

shaped

in part, in incomplete and contradictory ways, by concepts derived from

Marxist

class politics.

In 1952, Bolivia

experienced what was called the National Revolution. This was the most

extensive revolution in Latin America between the Mexican Revolution of

1910-17

and the Cuban Revolution of 1959. The 1952 revolution nationalized

Bolivia’s

main tin mines and, under enormous pressure from the peasantry, carried

out a

land reform. For the first time, it gave the vote to the majority of

the population,

which had been excluded on the pretext that you had to be able to read

and

write – in Spanish – in order to vote. There had been very few schools

in the

countryside and the elite had no interest whatsoever in the indigenous

majority

learning to read and write. Quite the contrary.

Despite the tin mine

nationalization, the land reform and the formal enfranchisement of the

indigenous majority, the 1952 National Revolution did not in fact

resolve any

of Bolivia’s main problems. It did not break its subordination to

imperialism,

particularly United States imperialism, which soon rebuilt a murderous

army for

the Nationalist government. It did not lift the country out of its

poverty. It

did not resolve the question of the land, nor did it change in a

fundamental

way the racist oppression of the indigenous majority; and it not change

the

fact that Bolivian miners, as was the case at the beginning of the 20th

century, continued and still continue to die on average before the age

of 40 because

their lungs are shredded by what they call the mal de mina

(mine sickness), which is silicosis and basically makes

you drown in your own blood.

I do not want to read a

long list of facts and figures, but a few may give you an idea of the

situation. According to the World Bank, over half of indigenous

Bolivians live

in what it calls extreme poverty; in the rural areas this rises to 72

percent.

The average income for indigenous people lucky enough to have a job is

US$63 a

month, compared to the average wage for non-indigenous people of US$140

a

month. So we are talking, literally, about starvation wages. Indigenous

women

workers face an unendurable triple oppression that really cannot be

affected by

the kind of timid reforms proposed by reformist organizations.

As for the land, one

hundred families own 25 million hectares of land (that’s about 100,000

square

miles). Meanwhile, two million work five million hectares of land

(under 20,000

square miles). In other words, even after the land reform carried out

and

trumpeted by the Nationalist regime that took power in 1952, the

concentration

of land in the hands of the wealthy has been spectacular. The land

hunger of

the poor peasantry remains a pressing issue.

Thus it is no accident,

given such conditions together with the protagonism of the

indigenous-derived

miners in national life, that Bolivia was a country where movements

claiming

allegiance to Trotskyism gained more influence than anywhere else on

the

continent. We will be talking more about this soon.

Morales’ Election No

Victory for the Exploited

So what about Evo Morales?

Everyone here probably remembers the coverage he got from different

parts of

the political spectrum when he won the December 2005 presidential

election.

Predictably, big-business newspapers denounced him as representing part

of what

they called a general “lurch to the demagogic left” in Latin America,

as the New York Times (24 December 2005) put

it. For its part, the international left was bubbling over with

enthusiasm for

“Evo,” saying that he represented a new kind of radicalism, even a new

kind of

socialism – a new, non-Marxist, non-class, special kind of radicalism.

They saw him as part of a

supposed left-wing realignment in Latin America that included

Venezuela’s Hugo

Chávez, a very vocal supporter of Evo Morales, and Lula’s

popular-front government

in Brazil. Morales also had the support of Cuba’s Fidel Castro, as we

saw at

the beginning of tonight’s forum in video footage that included “Fidel

and Evo”

going around shaking hands, kissing babies and so forth. According to

this

view, the realignment also included populist-flavored bourgeois regimes

in

Argentina, Ecuador, Peru and elsewhere.

People who put forward

this enthusiastic vision of Evo Morales pointed to the fact, which is

indeed

significant, that he is the first indigenous president in South

America. He is

not, as some claim, the first indigenous president in Latin America as

a whole:

that was Benito Juárez in Mexico, almost a century and a half

before Morales.

And they point to the fact that “Evo,” who is mainly known by his first

name in

Bolivia, became a political figure as leader of indigenous peasants who

were

fighting to defend what they view as their right – and what we as

revolutionaries very emphatically view as their right – to cultivate

the coca

leaf and sell it to whomever they can find to buy it.

The

peasant unions fought, sometimes in the face of enormous repression, to

defend

that right to grow and sell the coca leaf, in the face of the United

States’

so-called war on drugs. This “war” is a pretext not only for repression

in the

ghettos and barrios here in the U.S. but for military intervention in

many

countries of Latin America, including Bolivia. And it has included the

forcible

eradication of coca crops, sometimes by Bolivian troops on their own,

sometimes

together with U.S. “advisors” and soldiers.

With the social base he

developed among the coca-growing peasants in particular, Morales formed

a

nationalistic political party, first called the Political Instrument

for the

Sovereignty of the Peoples and then adopting the name MAS (Movimiento

al

Socialismo–Movement Towards Socialism). As running mate in one of his

early

presidential campaigns he chose Antonio Peredo, brother of Coco and

Inti

Peredo, two famous guerrilla combatants who had fought with Che Guevara.

Vice

President Álvaro García Linera outside Palacio Quemado in

La Paz, January 2007. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

Vice

President Álvaro García Linera outside Palacio Quemado in

La Paz, January 2007. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

In

his most recent, successful presidential campaign, Morales’ candidate

for vice

president was the country’s most prominent leftist intellectual,

Álvaro García

Linera, who was once a member of the Tupac Katari Guerrilla Army, named

after

the Aymara rebel who led a major uprising at the end of the 18th

century that

encircled the city of La Paz. That rebellion is still on the minds of

almost

all sectors of Bolivian society. Two years ago, when I was there during

the

overthrow of then-president Carlos Mesa, rich people who considered

themselves

part of the “white” elite were talking fearfully about what happened

during the

Tupac Katari rebellion of 1781 and indigenous people were talking

proudly about

the 1781 uprising. This history is still very much a part of the

country’s

political vocabulary.

In any event, Morales chose

as his running mate this intellectual who had been imprisoned for quite

a

while, was badly tortured because of his participation in the guerrilla

movement named after Tupac Katari, and subsequently became a

social-democratic-tinged ideologue of the MAS political party.

During the 2002 elections,

the U.S. embassy had inadvertently boosted Morales’ popularity when it

openly

warned against voting for him. You can see some of this in the recent

film Our Brand Is Crisis.1 In Bolivia the

American ambassador has

traditionally acted as an imperial proconsul, whose approval was needed

for

just about everything. If he said “don’t do that,” ministers and

presidents

were expected to obey, or else. But when U.S. spokesmen repeatedly

attacked

Morales as a supposed narco-terrorist, this backfired and strengthened

his

credentials as somebody seen as an anti-imperialist. In the December

2005

elections he won by an absolute majority, with 54% of the vote,

something quite

unheard-of in Bolivian elections. This was an indication of the degree

of

popularity he had gained among the indigenous population in particular.

Now according to most of

the left internationally, Morales’ election was a victory of the Indian

population, of the Bolivian peasantry and the laboring masses in

general. They

pointed to his wide popularity among that majority, who hoped he would

fulfill

their aspirations for fundamental social change. At the same time, a

number of

writers in the big-business press worried that if Morales didn’t make

some

serious changes pretty quickly, he could be outflanked on the left,

with

sections of his social base becoming more radical and impatient with

the pace

of change.

With few exceptions, most

currents on the left claimed that Morales’ victory was a victory of the

working

people of Bolivia. We – as Trotskyists, as Marxists – went very

strongly

against that rosy view of Evo Morales. We said, on the contrary,

before, during

and after the election, that his government would not in any sense be

socialist. We said that it would betray the aspirations of the

indigenous majority;

it would emphatically not represent

the interests of the Indian population of Bolivia, the working class,

or the laboring

and exploited population in general.

The League for the Fourth

International (LFI) emphasized that the government of Evo Morales would

not and

could not defeat the aggressive racist campaign waged against the

indigenous

peoples of the altiplano (the high

plateau around La Paz, Oruro and the main mining regions) by the elite

sectors

concentrated in the eastern part of the country and centered on the

agribusiness interests of the Santa Cruz “department” or province.

Not only would Evo’s

government not free the country from imperialism, we insisted, but in

fact the

new government would act as an enforcer

for imperialism and the rule of private property, in other words of the

ruling

class in Bolivia itself. In Marxist terms, despite the illusions spread

about

it, this would not be some sort of indefinite regime or hemi- semi-

demi-radical/whatever government with no class character. It would be a

bourgeois government.

This assertion produced

gasps of horror at our alleged sectarianism, ingrained intransigence

and

stubborn unwillingness, through sheer cussedness and overall nasty

ultraleftism,

one supposes, to recognize this “victory” and the supposed radicalism

of the

Morales regime. We stated in the publications of the LFI, The

Internationalist and El

Internacionalista, that we would not give a single vote to Evo and

would

have absolutely no confidence in his government; on the contrary, we

would

present a revolutionary opposition to that government.

We pointed out that Álvaro

García Linera, an elegant figure often seen in the fashionable

cafés of La Paz,

had coined a special phrase to describe the program of the MAS. He said

it

stood for something called “Andean capitalism,” a very special kind of

capitalism adapted to the high altitude and special conditions and

cultural

milieu of the Andes. Sometimes they would add the lowland areas and

call it

“Andean and Amazonian capitalism” (see “Bolivian Elections: Evo Morales

Tries

to Straddle an Abyss,” The Internationalist

No. 23, April-May 2006). Morales’ vice-presidential running mate said

that because

of the nature of Bolivia, this Andean capitalism would last for many

decades,

maybe even a hundred years.2

García Linera is not a

neophyte in politics, he is a top-flight intellectual who is famously

prolific

in his reading and his writing, so he justified this in the vocabulary

of those

who claim to have gone beyond Marxism to some higher, “postmodern”

plane. One

of the venues was at a university in Mexico City where he gave a speech

and

some of our comrades had a kind of debate with him from the floor.

García

Linera said, listen, you have to understand that there is no more

working class

in Bolivia – a claim that is echoed, surprisingly enough, by one

international

tendency that calls itself Trotskyist, as we will see. What you’ve got

to

understand, he said, is that in Bolivia there is no class

struggle any more; instead we have the action of “the multitudes,” las multitudes, which have no

particular class character, and this is actually a really good thing.

So these

multitudes or ever-shifting, amorphous masses have replaced the clash

of class

against class.

These are some of the

rhetorical devices that are swallowed hook, line and sinker by a

significant

number of ex-leftists. Anyone who recognizes that class struggle does

go on is

denounced as a dogmatic doctrinaire, and those who persist in

participating in

it are liable to find themselves repressed (undogmatically, no doubt)

by the

police and armed forces.

The MAS promised that

Bolivia’s problems would be resolved by calling a Constituent Assembly,

that

is, a convention to rewrite the constitution for the nth

time – Bolivia has had a lot

of constituent assemblies throughout its history. Evo Morales and his

followers

said that in some unstated way, this Constituent Assembly would refundar el país (refound the country).

Today they say this is part of a “democratic and cultural revolution,”

which

they sometimes subdivide into “four revolutions,” consisting of a

supposed

agrarian reform, fomenting “Andean capitalism” rather than the

“neoliberal

model,” reformulating educational policy, and so on.

When the government reached

its one-year mark García Linera thought it was a good time to

underline that

the so-called revolution “will continue its work so long as we can

guarantee

the support of workers, small businessmen, peasants, businessmen, the

Armed

Forces and Police” (La Razón, La Paz,

31 December 2006). In other words, so long as they can subordinate the

working

people to their exploiters and the armed forces that have carried out

so many

massacres to defend their rule. So no, this is not four revolutions, or

one

revolution, or any kind of revolution at all; it is a bourgeois

nationalist

regime.

How Evo Morales Proved

His Usefulness to the Bourgeoisie

We have stressed that to

understand the nature of Evo’s government, it’s essential to understand

how and why he came to power. How do you

explain that the leader of coca-growing peasants, who had been

demonized by the

U.S. ambassador and the Bolivian right, was able to take the

presidency? This

was a result of convulsive social struggles starting in the year 2000

with the

so-called Water War in Cochabamba, where the right-wing governor of the

departamento (province) tried to

privatize the city’s water system, leading to massive protests.

Particularly

key were what came to be known as Gas Wars I and II, which we covered

extensively in several articles in The

Internationalist No. 17 (October-November 2003) and No. 21 (Summer

2005).

The first Gas War broke out

in October 2003 to protest contracts signed with international oil and

gas

conglomerates by the right-wing president Gonzalo Sánchez de

Lozada, known as

“Goni.” These contracts basically gave away Bolivia’s gas wealth to

hated

international energy giants. There were huge protests which were met

with massive

repression. In previous forums we’ve showed some of the video footage

where you

could see the army firing on unarmed demonstrators from the hills,

shooting

dozens of people down. During these protests the country went to the

edge of

civil war. The question of a workers revolution was posed. This was not

our

deduction or interpretation, but something that was talked about in the

streets, in the markets, on the radio, in the press. The miners played

a

central role in fighting against the right-wing government with its

troops and

police.

Here is where we begin to

get an answer to the question I just asked. During the events of

October 2003

Evo Morales and his party, the MAS, performed a crucial service for the

Bolivian ruling class and its North American backers. The MAS played a

key role

in easing the transition from Goni to his vice president, who had the

same

politics but a softer image. This was Carlos Mesa, who happens to be a

prominent historian and journalist and was seen as a liberal

intellectual. And then

Morales and the MAS helped prop up Carlos Mesa in power.

But when Mesa’s government,

continuing Goni’s basic policies, promulgated a new gas and oil law,

the

protests renewed in Gas War II. In May and June 2005, massive protests

and

street fighting broke out, spearheaded, once again, by the miners.

Indigenous

peasants, poor people from the cities and students grouped themselves

around

the miners, who used their dynamite to defend themselves against army

sharpshooters and military police. There was an enormous polarization

of the

country: the Santa Cruz elite, grouped around hard-line right-wing

politicians

who were trying to take over the presidency, vowed to meter

bala: to shoot bullets into the Indian masses. They sharply

escalated racist rhetoric against the indigenous population, whom they

denounced as savages and barbarians.

The country was once again

on the edge of a civil war, culminating in the demonstrators driving

Congress

out of the capital: the Bolivian parliament had to run away from La

Paz! Congress

tried to set up shop in Sucre, one of the other main cities, where they

were

going to proclaim a right-wing government and perhaps a new state of

siege. It

came to a head when miners and peasant contingents were converging on

Sucre and

Juan Carlos Coro Mayta, a mine cooperative leader, was assassinated by

an army

sniper. I heard nightly discussions: is there going to be a military

coup, is

there going to be a civil war in the full sense, what are the

conditions that

could lead to a revolution, there is no revolutionary leadership at

this point

that could defeat the bourgeoisie and carry out a successful uprising,

and so

forth.

At that moment Evo Morales

and the MAS stepped in, as mediators to cool the situation out for the

ruling

class with another transition to yet another president from the same

bloc of

parties that had been in power. They wound up turning the presidency

over to

the head of the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, the leaders of the slum

dwellers’

associations of El Alto (the large, mainly Aymara working-class city

just above

La Paz), and the leaders of the El Alto regional labor confederation,

organized

a kind of side show. Together with people from the various left

parties,

including those who call themselves Trotskyists, they pulled together

something

they called the Asamblea Popular (People’s Assembly) and then the

Asamblea

Popular Nacional Originaria (National and Indigenous People’s Assembly)

or

APNO.

During its brief existence,

the APNO provided a platform for radical speeches and revolutionary

rhetoric,

but at the crucial moment the assembly’s main leaders helped the MAS

turn over

the reigns of power to the new president, who agreed to call early

elections.

Not accidentally, the leader of the El Alto slum dwellers’ association,

Abel

Mamani (who had been presented as a hero internationally by much of the

left),

was rewarded with a cabinet post when Evo Morales was elected six

months later.

He is a minister without portfolio, responsible for water. These guys

showed

they could chill the situation out for the ruling class. So half a year

after

the upsurge of May-June 2005 they were brought in to do just that. This

was not

a risk-free gamble for the bourgeoisie, since it did raise a lot of

expectations among the indigenous poor, but the traditional parties had

burned

themselves out and the ruling class needed new faces in office to keep

the old

order from going under.

Gestures, Rhetoric and

Reality

Evo

Morales (at right) in ceremony before his inauguration, at pre-Inca

ruins of Tiawanaku, 21 January 2006.

Evo

Morales (at right) in ceremony before his inauguration, at pre-Inca

ruins of Tiawanaku, 21 January 2006.

(Photo: David Mercado/Reuters)

Morales took office with a

series of symbolic gestures. In a video of his inauguration, which is

sold at

market stalls around the country, you get a look at how he changed the

presidential outfit when he took office. You wouldn’t believe how big a

deal

was made out of this. Instead of wearing a regular three-piece suit, he

had

some patches of Andean textiles sewn in. He had many, many pictures

taken with

Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez. Before the official swearing-in,

he went to

Tiawanaku, the pre-Inca ruins shown in the video, and had a ceremony

with yatiris (Aymara priests). At his

inauguration, he spoke about the historic oppression of native peoples

in

Bolivia, and called for a minute of silence for Manco Inca, the last

Inca

ruler, killed by Spanish conquistadors after an unsuccessful rebellion;

Tupac

Katari, whom I mentioned earlier; Tupac Amaru, leader of a major

uprising in

colonial Peru; Che Guevara, and many others.

But in this same speech,

after talking about the centuries of racist oppression dating back to

the

Spanish conquest, he went out of his way to give “a special greeting to

the

Prince and, above all, a special greeting to the Queen.” Guess which

prince and

queen? Of Spain. He told about visiting the royal family in Spain; it

was cold

there, and he caught a cold. Then he went to the queen and she got him

some

cold medicine. And so she went “from Queen to doctor for Evo Morales,

thank you

so much,” he said in his inaugural speech. So even at the symbolic

level, you

can see the balancing act. Homage to a series of heroes of the struggle

against

oppression. And then he turns around and makes special homage to his

friend,

the Queen of Spain.

It makes you want to say: Hello,

who was it that carried out the

Conquest? Who exactly carried out what Marx [in Capital]

called the “enslavement and entombment in mines of the

indigenous population,” leading, according to some estimates, to the

death of

five to six million in the mines of Potosí alone? It was under

the rule of the

Spanish Crown. Only after centuries did it gave way to United States

imperialism

as the dominant oppressor. So there was a point to Evo’s anecdote: he

was

telling the imperialists, especially those of Europe (who have had to

become

more sophisticated than their U.S. rivals) not to take the

anti-colonial discourse

too seriously.

Among the other symbolic

gestures Morales made when taking office, he named a former maid as

minister of

justice; he appointed as ambassador to France the great Quechua singer

from

Norte Potosí, Luzmila Carpio. He cut his own salary and that of

the vice

president and ministers. His foreign minister made some demagogic

statements,

like saying school children should get coca instead of milk for

breakfast.

These were like the former Ecuadoran populist president Abdala Bucaram

telling

the poor to take bottle caps and scratch rich people’s limousines:

posturing that

might irritate the upper crust and win some cheap popularity but was

not to be

taken seriously. In his second cabinet, named at the beginning of this

year,

Morales brought many leftists into the government, including several

from the

pro-Moscow as well as the Maoist Communist parties, plus former leaders

of the

miners’ union and of the COB labor federation. So he put faces from a

range of

“popular movements” into his cabinet.

In populist style, he used

these and other symbolic gestures and rhetoric to dress up actions that

serve

the ruling class. As soon as he took power, he emphasized that he would

respect

what in Latin America is called the “institutionality of the armed

forces,” in

other words the armed forces and officer corps would remain intact.

This is

particularly important if you remember that in Chile, the first thing

Salvador

Allende did when he was elected president in 1970 – as the head of the

Unidad

Popular, a “popular front” of class collaboration – was to swear to

maintain

the “institutionality of the armed forces,” which then turned around

and

overthrew him on 11 September 1973. In Bolivia, the armed forces have

carried

out innumerable massacres and military coups, so many that the country

was

nicknamed Golpilandia (Coup-Land).

This brings up another of

Evo’s gestures: the “Juancito Pinto Bond.” Towards the end of his first

year in

office he decreed a twice-yearly payout, equivalent to twenty-five U.S.

dollars, for school children in the first five grades of primary

school. This

is modeled on the “Hope Bond” distributed to school children by the

former

mayor of El Alto, who was driven out of power for siding with the Santa

Cruz

Oligarchy, and the “Solidarity Bond” for pensioners implemented by the

right-wing government of Goni. Juancito Pinto was a twelve-year-old

drummer boy

who died in 1880 during the Pacific War, when Bolivia lost its seacoast

to

Chile. This may look like sappy sentimentalism but it is actually an

appeal to

the revanchist anti-Chilean nationalism that has been whipped up by one

bourgeois government after another to divert struggle away from the Bolivian ruling class. Further

underlining his efforts to cozy up to the military, Morales had the

armed

forces distribute the money to the kids.

This brings me to something

else Morales did as soon as he was elected at the end of 2005. Right

away he

made a pilgrimage to Santa Cruz, the bastion of the hard-line

oligarchy, to

meet with the right-wing business leaders and say, “I don’t want to

expropriate

or confiscate any property.” Instead, he said, “I want to learn from

the

entrepreneurs” (Página 12, Buenos Aires, 28 December

2005). This is the

same business elite that was calling for Indian blood just a few months

before,

to shoot down the indigenous protesters on the altiplano. They have

their own

fascistic goon squads called the Juventud Cruceñista (Santa

Cruzist Youth),

which beat indigenous demonstrators bloody if they try to enter Santa

Cruz, and

have kept it largely union-free.

So beyond the gestures,

these are now substantial matters. When Morales met with the elite in

Santa

Cruz, they said: Listen Evo, you want to talk turkey, you want to make

nice?

OK, put your money where your mouth is. We want a bunch of things, but

the

first thing we want is the biggest iron and manganese deposit in the

world,

which happens to be in Bolivia, in a place called El Mutún. They

said: If you

want to cooperate and “learn from” us, here’s what we want you to do:

privatize

it. So Evo said: You got it. The government promptly announced that it

would

privatize Mutún, add a bunch of subsidies for international

investors, and turn

over this source of wealth which could, under a workers and peasants

government, be used for the working people. Eventually the contract to

exploit

Mutún was awarded to a company from India.

Agrarian “Reform”

Strengthens Landowners’ Power

The next measure was what

Morales and García Linera falsely called an agrarian reform or

“revolution,”

part of the supposed “four revolutions” trumpeted by their government.

As shown

in detail by the leftist Latin American Development Studies Center

(CEDLA) in

Bolivia, this supposed reform actually serves to consolidate the power

of big

landlords and agribusiness companies. I’ve mentioned the concentration

of land

in the hands of the rich and how little is in the hands of the poor

peasantry.

This situation is actually exacerbated

by the current “reform,” which is explicitly a continuation of the

Agrarian

Reform Law enacted by Goni, the hated right-wing, “neoliberal”

president overthrown

in 2003. Goni’s 1996 law is the basis of Morales’ supposed agrarian

reform,

except that Morales’ supposed reform is more

favorable to agribusiness than even Goni’s was.

This

is important, since the peasantry remains a large section of the

population

(about 35 percent of the population lives in the countryside, less than

in

previous times, partly due to the growth of towns like El Alto, but

still a

large sector). Moreover, it is Evo Morales’ historic base, while export

agriculture is one of the biggest sources of wealth and power for the

Bolivian

bourgeoisie. What happens with the land says a lot about what is really

going

on under this new government.

The Morales agrarian reform

takes a category from Goni’s 1996 law called FES or “social economic

function,”

a unit of production used as the definition of properties that are not

to be

touched by any agrarian reform measures. And it turns out that the FES

category

includes virtually all the lands

owned by agribusiness concerns. These huge farms for soy and other

commodities

will not be touched. In addition, the new version of the law broadens

the definition

of the FES to cover not only lands being cultivated or lying fallow in

order to

recover their productivity, but even those included in what it calls

“projected

growth.”

If you’re a huge landowner,

all you have to say is: Hey, I project that my business is going to

grow onto

that land and I will use it at some point. If you do that, your land

cannot be

touched. But what if part of their land falls within a category that

theoretically could be redistributed?

The “reform” gives landowners seven years to sanear las

tierras, to rearrange ownership, find a frontman, or get

around it in one or another way. Only after seven years would they have

to

respond to any hypothetical proposals to give out their land.

The agribusiness properties

are particularly concentrated in the department of Santa Cruz. In many

cases it

was the government, during years of subsidies to Santa Cruz, that gave

these

properties to the landowners. Concretely, 60

percent of the productive land is in Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, if

you’re an

agricultural worker you get beaten to a pulp if you even try to form a

union

there, and this region has been the staging ground for military coups

for many

decades.

Peasants

on hunger strike protesting continued eradication of coca fields by

Morales government, January 2007.

Peasants

on hunger strike protesting continued eradication of coca fields by

Morales government, January 2007.

(Photo: El Internacionalista)

So what is the Morales

government doing with regard to the needs of the peasantry, its

historic base?

Not only is it not fulfilling those needs, it is strengthening the

power of the

big landlords, and this is not just an economic question. It is a

social, political

and military question directly linked

to the fight against racism. Large landed property used for export

agribusiness: that is the basis of the political and military power of

many of

the most violent enemies of the Indian masses in Bolivia, the Santa

Cruz elite

in particular. That’s where they get their money and their power. If

you refuse

to touch their land, if you strengthen their control of it and even

give them

the ability to increase their wealth, you are not only not

solving the problems of the indigenous masses, you are

strengthening those who threaten to shoot them down whenever they

protest.

So if you want to know what

is meant by “Andean capitalism,” this

is what it means. Meanwhile, peasants have been trying to resist the

program of

coca eradication, which has not stopped under Evo Morales, despite the

fact

that he got his start by opposing it. When I was there a few months

ago, I

talked to coca-growing peasants who were on a hunger strike across from

the

presidential palace in central La Paz, the Palacio Quemado. They were

protesting against Morales and accusing him of continuing the U.S.

policy of

eradicating coca fields. They had posters with photos of fields that

had been

burned up by the army under Evo’s orders. And they were protesting the

killing

of two coca-growing peasants who were shot down in the Carrasco region

when it

was invaded by an army/police task force last October.

Fake Gas and Oil

Nationalization

One year ago, the measure

that made the biggest splash internationally was the supposed

nationalization

of Bolivia’s natural gas and oil. This was a high-profile event, in

which

Morales sent troops to stand outside the oil fields and refineries. He

made a

big speech on May Day 2006, saying that he was returning the historic

patrimony

of the Bolivian people by supposedly nationalizing the “hydrocarbons,”

gas and

oil.

This was a fake

nationalization. Nothing was nationalized, nothing was expropriated,

nothing

was confiscated, nothing was taken over. This was not even a bourgeois

nationalization

like those carried out in the 1930s and ’40s by national-populist

leaders like

Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico. It is interesting to see who

Evo’s Hydrocarbons

Minister was: Andrés Soliz Rada, who came out of a tendency

called Octubre,

linked to Argentine former Trotskyists who backed Peronism. He and his

group

were some of the most enthusiastic supporters of the nationalization of

Gulf

Oil carried out in Bolivia in 1969 by the military regime of General

Alfredo

Ovando. But Soliz Rada wound up resigning his post in the Morales

government in

September of last year, saying he could not go along with the

government’s soft

line towards what he called the “terrible demands” of the international

energy

companies.

Instead of any kind of

nationalization, what Morales did was rearrange the amounts of duties,

taxes

and royalties so the state would get a somewhat higher slice while

leaving the

property in the hands of the so-called multinational (in other words

imperialist) corporations. Our Brazilian comrades wrote a good article

which

exposed the phony character of this supposed nationalization while

denouncing

the threats by Brazilian president Lula and oil giant Petrobras (which

is

particularly concerned to maintain the flow of gas to the São

Paulo industrial

region), and defending Bolivia’s right to take measures regarding its

natural

resources. (See “Fake Gas

Nationalization in Bolivia: For Expropriation under Workers Control,” Vanguarda Operária No. 9, May 2006.)

In late 2006, Morales

negotiated a new contract with the president of Argentina, in which the

Argentine oil company YPFB and its senior partner, the Spanish Repsol

company –

one of the biggest of the international oil-business giants – would get

a

wonderful deal for cheap Bolivian gas at special prices. Not only did

they not nationalize oil and gas, they

strengthened the hand of various imperialist corporations, particularly

Repsol.

The government also raised

taxes on electrical companies, and increased those on mineral exports

from 3

percent to 15 percent, which is still a pittance. But what about the

properties

belonging to the most hated figure in recent Bolivian history, former

president

Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, who was the biggest mine owner in the

country? Seizing

them would have been enormously popular; even the opposition parties to

the

right of the MAS would have been hard put to raise much of a hue and

cry

against that. Yet the Morales government did no such thing. Goni quite

tranquilly

sold his properties to international mining concerns, a number of which

unveiled

new mining projects in Bolivia at the end of 2006.

In his “Report on One Year

in Office,” Morales cited statistics including the country’s fiscal

surplus and

that Bolivia’s Central Bank hit new records for international reserves,

partly

because of high natural gas prices on the world market. Behind the

figures was

a significant social and political fact: the Bolivian bourgeoisie was

enjoying

excellent and in some cases exceptional profits, as the new government

fomented

“social stability” through its efforts to lull the masses with populist

rhetoric and promises.

The Constituent

Assembly and Regional Polarization

In June 2005, at one of the

big marches held in the process of overthrowing then-president Carlos

Mesa,

there was a peasant contingent from the tropics of Cochabamba which was

quite

militant. Particularly the women marchers, who were armed with sticks

that had

nails through them and shouted cierren,

cierren (shut down) to all the stores and the people selling items

on the street.

If they didn’t shut down immediately the women would throw pebbles at

them, and

if they still didn’t shut down they would go at them with the sticks

with nails

through them.

I asked their leader what

slogans the contingent was putting forward. He said, “Yesterday it was

nationalization of oil and gas, but today our slogan is a Constituent

Assembly.”

This was in accordance with the orders from the MAS leadership. I asked

him,

“What do you think will come out of this Constituent Assembly?” He

said, “We

are going to refundar el país,”

refound the country. I asked, “What does that mean, what will it do?”

He said,

“We don’t really know, we just know we need to do that, and we’ll find

out what

it means later.” So in some way this Constituent Assembly was supposed

to

resolve the pressing issues through ostensibly democratic mechanisms

and not a

class struggle.

So after coming to power,

Morales held elections to the Constituent Assembly and convened it. As

of now

[May 2007], the assembly has been meeting for eight months. In eight

months it

has produced zero legislation; it has not written or rewritten a single

article

of the constitution. For seven months it debated its own rules of

procedure,

how its meetings would be run. Parts of the social and cultural elite,

including the son of the late union leader Juan Lechín, who is a

prominent

novelist, staged a supposed hunger strike (some reports said they were

getting

fried chicken delivered at night) to demand that the assembly not

approve its

decisions – which it wasn’t making – by a simple majority but instead

by two

thirds, so as to further block the possibility of any reforms. The MAS

zigzagged ridiculously, capitulating even on this terrain and further

emboldening the right.

Marchers

in La Paz, January 2007: “We Reject the 2/3,” referring to rule giving

right wing veto power in Constituent Assembly.

Marchers

in La Paz, January 2007: “We Reject the 2/3,” referring to rule giving

right wing veto power in Constituent Assembly.

(Photo: El Internacionalista)

We had stressed that the

Constituent Assembly was a supposedly democratic diversion that would

not solve

anything. Now what has happened with this talk shop, i.e. nothing,

underlines

that the basic issues in Bolivia cannot be resolved by a “democratic”

charade,

because they are issues of power, money, property and land; of

centuries-old

ethnic and linguistic oppression and discrimination; and they can only

be

resolved by struggle, on a class basis, a revolutionary basis. In other

words,

a struggle to defeat the enemies of

the indigenous masses and drive them from power, for they are not about

to let

themselves be talked out of existence.

One of the expressions of

Indian peoples’ oppression in Bolivia and much of the Andean region is

the

complete lack of language equality, that is, the history of

discrimination

against indigenous languages. Yet today, even the progressive call for

everyone

to learn indigenous languages in the schools has been linked through

the new

education laws to reactionary items on the agenda of the MAS

government, like

weakening university autonomy, which is extremely important throughout

Latin

America, and increasing state control over the teachers’ unions.

The regional polarization

between the Indian west and the eastern and southern regions known as

the media luna (half moon) has been one of

the hottest issues in recent years. An indication of how unequal things

continue to be is that the federal budget for 2007 dedicated nine times

as much

money per inhabitant for Pando, one of the departments that make up the

media luna, as for the department of La

Paz (La Razón, 20 December 2006). The

MAS found itself in a quandary over the provocative demand for

“regional

autonomy” by the racist civic leaders of the media luna,

who take advantage of all the democratic verbiage to make

a pseudo-democratic, actually anti-democratic demand, a power grab to

get even

more of the oil and gas revenue while running the region as their own

private,

“white”-ruled fiefdom. The peasants and poor people who voted for

Morales see

this for the racist ploy that it is and vehemently oppose it.

The MAS, however, has been

all over the map, so to speak, on this question, with Morales

eventually coming

out in support of “autonomy” for the media

luna as part of his conciliation of the Santa Cruz elite. His

supporters

hoped autonomy would be applied to Indian communities and then got

caught in a

trap when a national vote was held on the subject. Autonomy lost on the

national scale, but it won in the media

luna and the referendum specified that it would be applied in those

areas

where it won.

There was a new flare-up

while I was there at the beginning of the year. The prefect or governor

of Cochabamba

is a military man whose father was part of the most bloodthirsty

dictatorship,

the “narco-junta” of Colonel Luis García Meza in the early

1980s. This

governor, Manfred Reyes Villa, was himself trained at the U.S. School

of the

Americas, known as the “School of Assassins,” in Panama. He is a very

provocative, hard-line rightist. He decided to stir things up with a

new

autonomy referendum in Cochabamba as a show of support to the Santa

Cruz

leaders and a provocation against the indigenous peasantry of his own

region.

When Indian demonstrators

came into the city of Cochabamba to protest this, they were met with a

massive

show of force in which gangs of fascistic “white” youth, calling

themselves

Youth for Democracy, met them with metal bars, bats and guns, and

murdered some

of the protestors. These gangs were modeled on the Juventud

Cruceñista, which

according to some reports sent people to Cochabamba and has gotten

back-up from

old-line ultra-rightist and fascist groups like the Bolivian Falange,

which are

experiencing a resurgence. The population of Cochabamba mobilized,

including

many rank and file members of the MAS, which got its start in this

region. They

were on the verge of throwing out Manfred Reyes Villa, one of the worst

enemies

of the indigenous population. But the MAS leadership intervened, saying

no, you

cannot do that, you’re going too far, you have to respect

“institutionality”

and the rules of the game.

Morales Attacks the

Labor Movement

What about the Bolivian

labor movement, which has been at the center of many revolutionary

struggles in

the past and will be in the future? Morales has brought some labor

leaders into

his government, but some leaders of the miners’ union and COB national

labor

federation criticize him. In particular, the leaders of the La Paz

teachers’

union strongly criticize Evo Morales. This union has 20,000 members, is

a

prominent part of the COB, and is led by supporters of the main party

that

identifies itself as Trotskyist, the Partido Obrero Revolucionario

(Revolutionary Workers Party) of Guillermo Lora.

Acutely sensitive to

potential dangers on its left flank, the Morales regime reacted

strongly

against even rhetorical criticism from the COB. It was not enough for

the new

government party, the MAS, that the COB leaders were mainly blowing off

steam

and hot air accompanied by capitulations in practice to the new

bourgeois

regime. They wanted complete obedience.

So in populist style, the

MAS proclaimed it would form a parallel organization to the COB,

bringing

together various “social movements” in a pro-Morales grouping that

called

itself the People’s General Staff (EMP–Estado Mayor del Pueblo). This

included

MAS loyalists, the leaders of the Bolivian Communist Party and others.

They

wanted to make the unions toe the government line, either by

integrating them

into the regime or doing their best to break the unions’ power.

Displaying a

certain amount of hubris, they announced that the EMP would “take

complete

control of the COB” (La Razón, 19

April 2006). Their attempt to do this was short-lived and they had to

recognize

that it flopped, so they turned toward the second option.

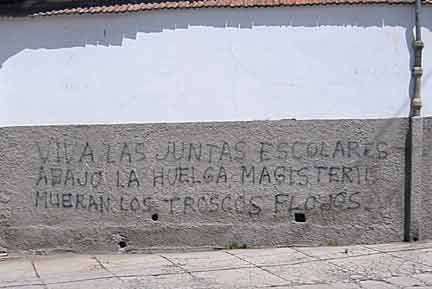

Slogans

of pro-government “school councils” say: “Down With the Teachers’

Strike. Death to the Lazy Trots.”

Slogans

of pro-government “school councils” say: “Down With the Teachers’

Strike. Death to the Lazy Trots.”

(Photo: El Internacionalista)

The teachers’ union was one

of their main targets, so the MAS first tried running in the union

elections,

but their candidates had a hard time of it. First they ran four

different MAS

slates, because of personal rivalries among their candidates, until

Morales got

on the phone from the presidential palace and told them to run a single

pro-government slate. But they still got very few votes, since their

candidates

had scabbed during the most recent teachers’ strike and had even gone

around to

several schools with the Minister of Education saying the strike was

illegal.

![]() When

they were unable to take over the teachers’ union, the so-called

People’s

General Staff joined with the juntas

escolares, neighborhood “school councils” originally formed by the

party of

ex-dictator Hugo Banzer to act as pro-government shock troops against

the

teachers under a kind of “community control” guise. They held a mass

march on

the teachers’ union hall, with the slogan “Death to the Trotskyist

Teachers!”

Graffiti with such slogans was sprayed on the walls all around the

union hall.

They pounded on the doors of the union hall, which were chained shut,

trying to

invade it and essentially lynch Vilma Plata, Gonzalo Soruco and other

leaders

of the union for criticizing Evo and continuing to carry out strikes.

This was

only stopped when the union managed to get on local radio stations to

call on

workers to oppose this union-busting assault. More recently, at last

month’s

[April 2007] convention of the El Alto Regional Labor Federation, there

was a

physical attack against miners’ leaders and other unionists and

leftists

critical of the pro-Morales leadership of Edgar Patana.

When

they were unable to take over the teachers’ union, the so-called

People’s

General Staff joined with the juntas

escolares, neighborhood “school councils” originally formed by the

party of

ex-dictator Hugo Banzer to act as pro-government shock troops against

the

teachers under a kind of “community control” guise. They held a mass

march on

the teachers’ union hall, with the slogan “Death to the Trotskyist

Teachers!”

Graffiti with such slogans was sprayed on the walls all around the

union hall.

They pounded on the doors of the union hall, which were chained shut,

trying to

invade it and essentially lynch Vilma Plata, Gonzalo Soruco and other

leaders

of the union for criticizing Evo and continuing to carry out strikes.

This was

only stopped when the union managed to get on local radio stations to

call on

workers to oppose this union-busting assault. More recently, at last

month’s

[April 2007] convention of the El Alto Regional Labor Federation, there

was a

physical attack against miners’ leaders and other unionists and

leftists

critical of the pro-Morales leadership of Edgar Patana.

The most spectacular

recent event was the pitched battle that occurred last October in the

mining

center of Huanuni between two groups of miners, the basis for which was

set by

the MAS government. A few years back, the workers at Huanuni, presently

the

most important mine in Bolivia with a long tradition of militancy,

succeeded in

having the mine renationalized through a very important struggle. These

workers

are members of the national mine workers’ union federation, work for

wages

under a union contract, and are employed by the state mining company,

Comibol.

At the same time, there is another sector, called the cooperativist

miners

because they are members of cooperatives that work separate mine

sections and

sell the minerals. Many of these miners are very poor, while other

cooperative

members act like contractors and in effect live off the poorer ones.

The Morales government,

which had received the support of the cooperative leaders, basically

encouraged

them to attack the unionized miners and seize a larger part of the

mountains in

this area for themselves. Vice President García Linera

infamously said that he

was prepared to “send coffins” to Huanuni. The government got their

coffins,

their dead miners on both sides in this conflict. At least 16 miners

died and

dozens were wounded.

But even though the union

miners were in the minority, they defended themselves with dynamite,

and were

actually able to prevail. And then they did a very interesting thing.

Instead

of trying to get vengeance against the ranks of the cooperative miners,

they

did the opposite, saying: Here is what we want to come out of this

situation;

we demand that the state mining company Comibol hire

the cooperativist miners. With this demand they were able to

get approximately 1,500 of those miners hired on, more than doubling

the size

of the unionized workforce at Huanuni. This was a victory for the

working

class, but one that came, as is so often the case in Bolivia, with

miners’

blood.3

The Fight for Genuine

Trotskyism

Because events in Bolivia

give a particularly sharp expression to crucial issues of the class

struggle,

they often highlight important aspects of the fight for revolutionary

leadership. One is the meaning of internationalism itself. Here in the

United

States, the attitude of most of the left has been to tail after Evo

Morales.

Articles by radical groups and leftist academics have focused on the

scope of

social movements, the hopes of the oppressed masses, and the fact that

Morales

is the first indigenous president. These are important facts, but if

you do not

look at the actual content of

political events then you are doing no service, you are just being

liberals.

When they are not engaged in more direct social-patriotic capitulations

to

their “own” ruling class, what passes for international solidarity

among U.S.

leftists is all too often the kind of uncritical enthusing that smacks

of liberal

paternalism.

In contrast, genuine

international solidarity is based on the interests of the only

international

class, the proletariat, and means in the first place telling the truth,

which

requires taking the trouble to find out the real nature of the Morales

regime.

We defend Bolivia, a semi-colonial country oppressed by imperialism,

against

any kind of aggression by the U.S., and we would militarily defend the

Morales

government against imperialism in the event of such attacks. But

telling tall

tales about the supposed revolutionary nature of this bourgeois

government is counterposed to any real struggle

against imperialism.

A striking example of how

misleading reporting can get, when reality is subordinated to tailism,

was the

International Socialist Organization’s coverage of the events that set

the

stage for Evo Morales to win the elections, specifically the fall of

Carlos

Mesa in 2005. The ISO is a social-democratic group, presently the

largest left

tendency on U.S. college campuses, known for supporting Ralph Nader

(who is no

friend of Latin American workers that come here as what he calls

“illegal

aliens”). Their press runs fairly frequent coverage of Bolivia. In June

2005,

as I mentioned, Evo Morales and the leaders of peasant, labor and left

organizations

stole victory from the masses, heading off the threat of revolution by

demobilizing the marches, road blockades and strikes in order to turn

the

presidency over to the head of the Supreme Court. But what was the

headline in

the ISO paper? “Victory in Bolivia!” (Socialist

Worker, 17 June 2005).

While “the fight for

nationalization of gas and oil is not yet resolved,” they wrote, the

“social

movements have delivered a stunning blow to the Bolivian oligarchy and

U.S.

imperialism.” By Goni’s vice president being replaced by the head of

his

Supreme Court? Hardly. The ISO went on to report favorably that the

“issue of

organizing for the Constituent Assembly will take priority for the most

radicalized sectors of the social movements.”

Then there is the Spartacist

League, which unlike the ISO actually used to be Trotskyist. Those days

are

long gone, however, as illustrated very starkly by their position that

a

socialist revolution cannot happen in Bolivia. And why is that?

Because, they

claim, there is no working class there! As you will recall, this

happens to be

the line of Vice President García Linera, for whom “the wish

begets the

thought”: he’d certainly like radical miners and other inconvenient

workers to

be non-existent.

At a New York antiwar march

in April 2006, a member of the Spartacist tendency’s international

leadership

tried to disabuse me of the idea that those workers really exist. He

told me

that after a vigorous search – on the Internet – they’d found,

supposedly, that

no enterprises of more than 150 employees exist in Bolivia. When I

replied that

even a cursory Web search would have disproved this ridiculous claim,

and asked

if they had ever heard of Huanuni and Comibol, he said with a certain

degree of Schadenfreude: “Comibol is kaput.”

According to them, we “conjure

up a proletariat where it barely, if at all, exists” (see “Spartacist

League

Disappears the Bolivian Proletariat,” The Internationalist No.

24,

Summer 2006).

Bolivian proletariat “barely, if at all, exists”? Look for yourself. Miners

rally during June 2005 worker-

peasant mobilization. (Internationalist

photo)

Really, now? An old adage

says nobody is as blind as he who will not see; in this case people who

have

turned historical pessimism and adaptation to the labor aristocracy

into a

political program. This is the opposite

of internationalism. Since the Spartacist League is clearly indifferent

if not

outright hostile to proletarian struggle in Bolivia, it can only be an

embarrassment to them that the Huanuni miners and the rest of the

Bolivian

proletariat keep refusing to go away. For workers in Bolivia, it is

clearly a

good thing that neither the ISO nor the Spartacist League,

revolutionaries in

word only, have the slightest chance of ever having any influence there.

In Bolivia itself, however,

several currents of the left have had a major impact within the workers

movement. This is why the MAS seeks to co-opt those it can and crack

down on

the rest. I mentioned the former Guevarists like Antonio Peredo who are

prominent in the MAS. The Bolivian Communist Party also backs Morales

and

joined his government. They justify this with the old Stalinist schema

of a

“two-stage revolution,” in which Morales heads a “national-democratic”

regime,

supposedly leading the way in some far distant future to a second,

socialist

stage. In reality, the first, “democratic” stage regularly leads to a

massacre

of the workers and peasants. The pro-Moscow Stalinists control the

nationwide

teachers’ federation and at various times were influential in the

miners’ and

factory workers’ unions. They are joined by their not-so-distant

cousins, the

Maoists: Luis Alberto Echazú, long a spokesman for Bolivia’s

small Maoist party

(Partido Comunista Marxista-Leninista), is now the Minister of Mines.

Many current and former

leaders of the COB national labor federation have talked now and again

about

setting up a kind of pressure group on the Morales government, which

they call

an Instrumento Político de los Trabajadores (IPT), political

instrument of the

workers. If this sounds vague, that’s because it is meant to be really

vague. A

“political instrument of the workers” could be just about anything to

anybody,

a sort of amorphous conglomeration that is pointedly not a Marxist,

revolutionary or Trotskyist party. They were joined in this call for an

“IPT”

by one of the smaller groups in Bolivia that identifies itself as

Trotskyist,

the LORCI (Revolutionary Workers League–Fourth International), which

also tried

to set up a “COB Youth” for the bureaucracy. The LORCI is part of the

tendency

led by the Argentine PTS that comes out of the movement of followers of

Nahuel

Moreno.

There is also a small

official Morenoite group in Bolivia (the Movimiento Socialista de los

Trabajadores), which used to brag about being advisors to Evo and is

now a university-based

cheering squad for the COB leadership. From Argentina, the Partido

Obrero of

Jorge Altamira actively campaigned for Evo Morales and sent a

delegation to his

inauguration. This led to the near-dissolution of the small Bolivian

group

aligned with them, the Oposición Trotskysta, which had already

gone through a

series of crises and almost ceased to exist.

The main organization in

Bolivia that calls itself Trotskyist is the POR: the Revolutionary

Workers

Party of Guillermo Lora, whose supporters lead the teachers union of La

Paz.

Historically this party had a significant presence among the miners and

a big

impact on the ideology of the miners’ union, the backbone of the

workers

movement. However, this was conditioned through the POR’s long years of

alliance

with the nationalist leaders of the miners’ union, most importantly

Juan

Lechín. From the 1940s through the ’80s Lechín was the

main leader of the

miners’ union, and then of the COB as well. A member of the nationalist

party

(MNR), he was key to subordinating the workers to the MNR government

that took

power in 1952.

The POR’s alliance with

these leaders was in a sense codified six years before the 1952

revolution,

when the miners’ union approved the famous Tesis

de Pulacayo, the Pulacayo Theses. Written by the POR, this was a

document

of political and ideological orientation for the Bolivian labor

movement. While

it reflected and contributed to working-class radicalization, it

embodied some

dangerous contradictions. The Theses used slogans and demands taken

from

Trotsky’s Transitional Program of the Fourth International, while in a

significant sense it was syndicalist, evading the question of the

revolutionary

party. But this was no accident, and the problem went even deeper,

since the

Theses played an important part in bolstering the supposedly

revolutionary

credentials of nationalist labor

leaders like Lechín, who were members

of a party – the bourgeois-nationalist MNR – and then became a crucial

part of

the MNR government in 1952.

Today the POR strongly

criticizes Evo Morales. To pick one example, their paper Masas

(12 January) ran a front-page headline. It’s a long one:

“Completing One Year in Government, the MAS Reaffirms its Pro-Bourgeois

– That

Is, Counterrevolutionary – Content.” The POR presents itself as the

very

incarnation of Trotskyism, and over the years its ranks have included

many

courageous and self-sacrificing militants. However, this party

demonstrated its

real nature during three major

revolutionary opportunities in Bolivia, when what it did was the

opposite of

fighting for the Trotskyist program of permanent revolution.

The first was the “National

Revolution”: during and for years after 1952, the POR supported

Lechín’s left

wing of the MNR, helping cement illusions in the bourgeois government.

Then,

during the major working-class and student upsurge of 1971, the POR

helped

Lechín form a “People’s Assembly” which served as a

sounding-board for the

left-talking nationalist regime of General Juan José Torres. In

the face of

open preparations for a right-wing coup, this assembly did nothing

to prepare the masses to defend themselves, and then

stopped meeting at all for the seven weeks leading up to the coup.

After the

terrible military coup of August 1971, the POR formed its own popular

front,

the “Revolutionary Anti-Imperialist Front,” with the exiled President

Torres,

who had in fact paved the way for the right-wing takeover.

The third time around was

in 1985, when more than 10,000 miners occupied La Paz against the

popular-front

government of Hernán Siles Zuazo, which was applying austerity

measures

dictated by the International Monetary Fund. After opposing the call

for

soviets (workers councils), the POR made another front with

Lechín just at the

moment when he sold out and demobilized the miners, who were soon

punished with

mass mine closures and the vicious program to “relocalize” them and

destroy

their power. In each of these situations, the POR made a bloc with

nationalist

leaders who subordinated the working people to one or another

capitalist

government, and thereby to imperialism.

Labor demonstration in La Paz, March 1985. At crucial moment, the POR of Guillermo Lora made

political bloc with bourgeois nationalist Juan Lechín, leader of COB union federation, who again

headed off potential workers revolution. (Photo: Ed Young)

In 2005, during the

overthrow of Carlos Mesa, this pattern was repeated once again. It was

extremely dramatic. The miners were in the streets, hurling dynamite to

defend

themselves against the sharpshooters of the army; thousands of peasants

and

slum-dwellers were streaming into the capital. Yet the position of the

POR was

to call for another “People’s Assembly, like in 1971.” So they formed a

“people’s

assembly,” later renamed the National and Indigenous People’s Assembly

(APNO)

as I mentioned earlier, where the leaders of the labor federations and

neighborhood associations would get up and make all these revolutionary

speeches. Then those leaders helped turn power over to the president of

the

Supreme Court. The POR was seconded in this bloc by the LORCI, which

subsequently played a role in building a union of airport workers in La

Paz,

and sometimes makes leftish criticisms of the POR. However, the LORCI

is

frequently to the right of the POR, as in its abject tailing of the

call for a

constituent assembly, which the LORCI tried to prettify by calling for

a

“revolutionary” constituent assembly.

There is a follow-up to the

story of what the POR, the LORCI and other leftists did with the

“People’s

Assembly.” I mentioned how last year government supporters tried to use

the

“People’s General Staff” to take over the COB in their attempts to

subordinate

the labor movement completely to the government. The man those

government supporters

wanted to take over the COB was Edgar Patana, head of the El Alto labor

federation. Patana had provided crucial services to Morales and the

bourgeoisie

when the government of Carlos Mesa fell in June 2005. And in June 2005,

Patana

was one of the main figures in the “People’s Assembly” using the

radical

rhetoric to defuse the threat of revolution and ease the power

“transition” to

the Supreme Court chief. He was one of the leaders who got a left cover

there

from the POR, the LORCI and the other leftists in that ill-fated

People’s

Assembly (See “Myth and Reality: El Alto and the ‘People’s Assembly’,” The Internationalist No. 21, Summer

2005). They like to use populist, classless references to “the people”

in

general, so they wanted their “People’s” Assembly – and what they got

is this

reactionary “People’s” General Staff, directed against them.

It is just the latest episode of a recurrent

nightmare for the workers and oppressed, which will only end through

building a

real revolutionary leadership, a genuine Trotskyist party.

Bolivia and Permanent

Revolution

I

want to end by emphasizing that the program of permanent revolution is

very

much on the agenda in Bolivia today. This is the urgency of fighting to

build

the nucleus of a Trotskyist party which would actually be able to bring

the

masses’ long-held aspirations to fruition.

On the land question,

rather than a phony agrarian reform, what’s necessary is a real

agrarian

revolution in which the poor peasantry seizes the landed estates and

agribusiness properties, protecting this through self-defense bodies in

close