|

Military

Scandal Reveals:

Army

Death List Targeted

Brazilian

Worker Militants

The following article is translated from the April 2000 special supplement

to Vanguarda Operária, newspaper of the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista

do Brasil.

“CAPTURE AND NEUTRALIZATION”: The words evoke the death

squads that terrorized an entire continent, from the Southern Cone to Central

America. And they come from Brazilian military officers seeking to exterminate

the “subversives” who dare to organize struggles of the exploited and oppressed.

Yet this is not a story from the darkest years of the dictatorship that

ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985. Recent spectacular revelations–unveiling

the terrorist activities of the armed forces against workers struggles

in the steel city of Volta Redonda a decade ago–show the iron fist of the

capitalist state in today’s bourgeois “democracy,” in force in Brazil since

the military turned power over to civilian politicians. The same conspirators

and specialists in repression remain in the officer corps today, under

the government of president Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

These revelations are the tip of the iceberg of what the press has called

Brazil’s “parallel military government.” The topic returned to the headlines

recently when high-ranking officers unleashed a torrent of threats and

insults against the creation of a Defense Ministry supposedly subordinated

to civilian government structures. Contrary to the illusions sown by reformists

and popular frontists, it is not possible to “democratize” or reform the

armed forces, which exist to defend the power of the ruling class.

Repression is not simply the work of this or that individual, nor of

the particular government currently inhabiting the Planalto presidential

palace. It is a function of the capitalist state, which in Friedrich Engels’

famous definition boils down to “special bodies of armed men” whose purpose

is to defend the exploiters’ rule. During the investigation of the crimes

committed by the army during the repression of the 1970s guerrilla movement

in Araguaia (central Brazil), the chairman of the ultra-reformist Partido

Comunista do Brasil (PCdoB) used his May 1996 testimony in the chamber

of deputies to proclaim that his party is not an “inflexible opponent of

the Armed Forces,” which “have an important role to play.” Yet the entire

history of the class struggle shows that the role of the bourgeois armed

forces is bloody repression in the service of the exploiters. The struggles

of the oppressed must aim at sweeping away the entire capitalist system

and its repressive apparatus through international socialist revolution.

Only in this way can the working people of the cities and countryside defend

themselves against the terror of the armed fist of the bourgeoisie.

The recent wave of revelations began in March 1999 with the publication

of testimony by Dalton Roberto de Melo Franco, a former captain in the

First Special Forces Battalion, regarding the bomb that destroyed the memorial

to the workers killed by the army during the great 1988 Volta Redonda steel

strike. This was followed in June by an official inquiry into the Riocentro

incident, in which a bomb exploded near a May Day concert attended by 20,000

people in Rio de Janeiro in 1981. And in August of last year, a military

officer revealed that the commander of the Special Forces prepared a

list for the “clandestine capture” and “neutralization” of seven leaders

of the strike which paralyzed the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional

steel plant, Latin America’s largest, for 31 days in 1990, among them our

comrade Cerezo (Carlos Alexandre Honorato). Make no mistake: this was a

hit list of people to be killed.

Almost ten years after being fired in the wake of the 1990 strike, Cerezo

recently returned to his job as a welder at the CSN steel plant after winning

a legal judgment against the company. The local journal Aqui (12

December 1999) called the event “The Victory of Determination,” observing:

“What distinguishes Cerezo’s story from that of the other trade unionists

involved [in the 1990 firings] is what happened between then and now. The

welder refused to make a deal with the company because he wanted to uphold

the basic right to return to work,” not only for himself but for all those

fired. After many years, a labor relations court “finally granted him a

ruling returning him to his former job.” Aqui noted as well that

“together with other activists, he founded the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista

do Brasil, which publishes the Vanguarda Operária newspaper.”

The Bourgeois State: Terror Machine

Against the Exploited

Cerezo was recently interviewed by The Internationalist, publication

of the Internationalist Group. (The IG, like the LQB, is a section of the

League for the Fourth International.) In the future we will publish more

of this interview; here we will focus on drawing the lessons of the 1990

events. As Cerezo points out:

“With the exit of the military dictatorship and the establishment

of bourgeois ‘democracy,’ there was no basic change for the workers. The

army, the military and local police all remained and would occupy CSN when

the workers went on strike.... It didn’t change the life of the steel workers,

who were still persecuted by the army, the municipal and Military Police

as well as CSN’s own police force.”

Volta Redonda had been a “National Security Area” under the military dictatorship.

Officially this came to an end in 1985, but in reality it continued eight

more years, with the presence of the 22nd Motorized Infantry Battalion

in the neighboring city of Barra Mansa.

During the great strike of 1988, in which comrade Cerezo was a member

of the strike committee, the army invaded the plant, wounding 46 workers

and murdering William Fernandes Leite (22 years old), Valmir Freitas Monteiro

(27) and Carlos Augusto Barroso (19) on November 9. Yet even the military

invasion and the betrayals of the union bureaucracy did not succeed in

breaking the spirit of the steel workers, who resisted in the streets and

inside the factory itself, where they faced off against army tanks and

occupied the plant’s rooftops, throwing stones–and even lime–at the soldiers

below. The bourgeoisie and its armed forces viewed with an abiding hatred

the workers of Volta Redonda, who won a six-hour day at CSN as a result

of this strike.

Internationalist photo

Volta Redonda monument

to steel workers

William, Valmir and Barroso,

killed on 9

November 1988 in army

attack on CSN strike.

Army squad blew up original

monument the

day after it was inaugurated.

As a direct provocation against the workers, in September 1999 president

Cardoso nominated army general José Luiz Lopes da Silva, who

commanded the invasion of CSN in which three strikers were killed, to

the Superior Court of Military Justice, which oversees trials against military

personnel. The government’s supporters were mobilized to ram the nomination

through the Senate. In testimony before the Constitution and Justice Commission

which rubber-stamped his nomination, general Lopes spoke of the invasion

with pride: “From a military point of view it was a complete success” (O

Estado de S. Paulo, 7 October 1999).

Lopes was not the only one rewarded for his bloody attempts to smash

the workers’ resistance. Already in 1989 four Rio de Janeiro Military Police

officers were decorated with the “Peacemaker” medal for their actions during

the invasion of the struck CSN plant. In fact, an important role was played

in the invasion by the Military Police, which worked closely together with

the army. As Cerezo observes in the interview:

“Our entire experience with regard to the police underlines

the point we always make: that cops of all kinds are not part of the workers

movement.... When we carried out the fight to expel the guardas [municipal

police] from the Volta Redonda municipal workers union, this was influenced

not only by the lessons of theory–such as Trotsky’s explanation, in his

writings on Germany and elsewhere, that police must not be part of the

unions–but also by our own experience of living through this police repression.”

On May Day 1989, a memorial to the slain strikers William, Valmir and Barroso,

designed by the renowned Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, was inaugurated

in Volta Redonda. As Cerezo notes, “during the early hours of the following

day, army commandos blew up the monument as an act of revenge against the

steel workers and against the memory of what happened.” The shock waves

from the explosion–a symbolic second murder of the fallen strikers–shattered

windows a thousand feet away. Another explosive charge, which failed to

detonate, was found near the ruins of the memorial.

Reserve general Newton Cruz, whose former posts included military commandant

of the presidential palace and chief of the Central Agency of the National

Intelligence Service, said at the time that he applauded the authors of

the bomb plot. Nevertheless, armed forces spokesmen sought to cover up

the truth by roundly denying any military involvement in the attack.

Cerezo recalls:

“Several days later the workers moved to rebuild the memorial,

mixing the concrete themselves. It was striking how the army used blackmail

to make sure no cranes would be made available and no company would take

up the project to reconstruct the memorial. So all the various companies

which were approached for the job refused to do it, and told people this

was because of the army’s threats. The workers decided to put the memorial

back up with their own hands.”

The blowing up of the monument also intensified many workers’ doubts and

suspicions about the death, three months previously, of steel union leader

José Juarez Antunes, who had led the 1988 strike. Juarez was elected

mayor of Volta Redonda after the strike and had been in office 51 days

when he died in a supposed auto accident.

The bishop of Volta Redonda, Waldyr Calheiros, has stated that a Federal

Police agent warned him at the time that both he and Juarez had been marked

for assassination in “accidents” that were supposed to occur in areas far

from the city (Diário do Vale, 17 March 1999). Although Juarez

was elected as a candidate of the Partido Democrático Trabalhista

(PDT), the populist bourgeois party of Leonel Brizola, many capitalists

and military officers considered his election an act of defiance and an

insult against “order” by the workers. Later, death threats were made against

former union president Marcelo Felício (who has now gone over to

Cardoso’s party) and a lawyer hired by the union to investigate the death

of Juarez.

The Revelations of Ex-Captain Franco

The existence of the death list against Cerezo and other leaders of

the 1990 strike came out as part of the series of revelations about the

attack on the November Ninth Monument, as well as other facets of military

terror, that shook Brazil over the course of several months last year.

The 1990 strike broke out in July of that year against the bourgeoisie’s

campaign to go after the CSN workers in preparation for privatizing the

company. The sequence of events provides insight into the machinery of

bourgeois state power in Brazil.

In April 1999, Jornal do Brasil, one of the country’s leading

dailies, published the revelations of Dalton Roberto de Melo Franco, a

former captain in the army’s First Special Forces Battalion. Franco originally

made his declarations as part of his defense in a military trial held in

December 1998, in which he was accused of “diverting munitions” eight years

earlier. He said he had been persecuted by a number of higher officers,

among them the notorious general José Siqueira, former secretary

of security in the Rio state government and a friend of populist leader

Leonel Brizola.

Jornal do Brasil

Former captain Franco

(circled, right) revealed that General Álvaro de

Souza Pinheiro (circled,

left) gave the order to blow up the November Ninth

Memorial to the three

Volta Redonda workers killed by army in 1988 strike.

Describing himself as the victim of a military frame-up, ex-captain

Franco said he had been punished and then expelled from the army because

he was ordered to participate in blowing up the November Ninth Monument

in Volta Redonda but refused to do so unless he was given the order in

writing. Franco had been part of a group of Special Forces officers that

the army infiltrated into CSN in 1988 with the mission of identifying and

“rapidly isolating the leaders” when troops invaded the plant. He noted

that the following year, when plans for unveiling the monument were underway,

“the army considered this an affront, that the intent was to create martyrs”

(Jornal do Brasil, 14 March 1999).

Franco said he received the order to blow up the monument from then-colonel

(now general) Álvaro de Souza Pinheiro; when he refused, the task

was carried out by other agents. “The dynamite came from a group of numbers-runners

who obtained it from stone quarries in the Baixada Fluminense region. They

helped put together a storehouse of munitions to be used subsequently in

irregular operations,” he related. The dynamite was kept in camouflage

knapsacks that were part of a shipment of arms and matériel the

army had seized from a Panamian-registered ship in 1986.

Franco went on to describe the activities of his former battalion, clearly

modeled on the U.S. Special Forces “green berets” units, specialized in

counterinsurgency and “unconventional” warfare, which were used by the

United States to carry out terrorism and extermination operations in Vietnam.

As the Jornal do Brasil described it:

“The First Special Forces Battalion is the apple of the eye

of any commander of the Brazilian Army. Created in the 1960s, it is made

up of soldiers renowned as Rambo-style warriors.”

Franco related that in his more than ten years in the battalion, he carried

out espionage assignments in all the countries neighboring Brazil, from

Argentina to Guyana. General Pinheiro had participated in the repression

of the Araguaia guerrilla movement, and according to Franco the battalion

carried out counterinsurgency missions in Colombia, Nicaragua and El Salvador.

In the early ’90s, he said, Brazilian Special Forces soldiers were in El

Salvador on the eve of the “peace” accords between the Salvadoran government

and the FMLN guerrillas. “There were sectors of the rebel movement that

didn’t like the accords. Our detachment provided support to a group of

American counter-guerrilla troops,” Franco stated.

A Chain of Attacks and Provocations

In response to the scandal set off by ex-captain Franco, the army established

a Military Police Inquiry (IPM, from its initials in Portuguese) to “investigate”

his revelations. And who appointed the officer in charge of this IPM? The

same general José Luiz Lopes who commanded the invasion of CSN in

1988, and today heads the army’s Eastern Military Command. The IPM

was accompanied by a special commission of the Rio de Janeiro state assembly

which “united” the legislators, from the popular-frontist “opposition”

of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (the Workers Party of Luiz Inácio

Lula da Silva), the PCdoB and their bourgeois partners in Brizola’s PDT,

the Partido Socialista Brasileiro of the landowner Miguel Arraes, etc.

For his part, Luiz de Oliveira Rodrigues of the pro-company labor federation

Força Sindical called the inquiry “good for the Army and good for

society” (Diário do Vale, 18 March 1999). Thus “Luizinho,”

who promoted the establishment of union-company “partnership” at CSN when

the steel plant was privatized in 1993, used the occasion to underline

yet again his loyalty to the exploiters and their state.

There have been so many parliamentary investigative commissions (CPIs)

into one scandal after another that the bourgeois press has taken to calling

Brazil “the land of the CPIs.” As for the Military Police Inquiry, this

is a clear example of the continuity of many institutions of today’s “Brazilian

democracy” with the old military dictatorship. As part of the “Great Strategy

of the Doctrine of National Security,” the institution of IPMs was created

in 1964, after the military coup carried out that year, specifically as

a tool to identify and root out “subversive” elements. The bourgeois “justice”

system, in both its military and civil incarnations, exists to defend the

rule of the capitalist class, which in Brazil means racist, anti-working-class

terror. Some months ago, the press revealed the “disappearance,” in São

Paulo alone, of more than 1,100 inquiries and lawsuits accusing members

of the Military Police of serious crimes, 80 percent of which had to do

with the murder of civilians, many of them minors (O Globo, 23 May

1999).

The most famous IPM in Brazilian history, on the Riocentro affair, returned

to the headlines in recent months in the context of the revelations by

ex-captain Franco. On the night of 30 April 1981, a bomb exploded inside

a car carrying two officers of the armed forces’ terror and torture unit

DOI-CODI (Intelligence Operations Detachment-Center for Internal Defense

Operations), killing one and gravely wounding the other. The incident occurred

at a turning point in Brazil, after the huge metal workers’ strikes at

the end of the 1970s. The bomb blew up near the Riocentro arena, where

20,000 people were attending a show to celebrate May Day featuring several

of the countries’ most popular musicians, among them Milton Nascimento,

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. The original IPM on the Riocentro incident

declared the explosion to have been the work of anti-army “terrorists,”

and this brazen fraud was used to whip up more white terror against “subversives.”

Almost two decades later, faced with Franco’s declarations in 1999,

the army confronted growing pressure to reopen the Riocentro case. The

armed forces’ first response was a scarcely veiled threat: the commander

of the army declared that calls to reopen the case “disturbed” the military

and demanded an “end to resentments and discord.” When this failed to do

the trick, the second response was to mount a damage-control operation

through a new IPM. Even the bourgeois daily O Globo (9 May 1999)

warned that the result could be “to avoid having the IPM wind up revealing

the inner workings of the parallel military government of the 1980s, tarnishing

records and stirring up military circles on the eve of the creation of

the Ministry of Defense.” Thus the decision was made to sacrifice Wilson

Machado, the officer who survived the 1981 explosion, and general Newton

Cruz, charging Machado with homicide and Cruz with perjury and disobedience.

After an attempt to maintain silence with the argument that the 1964 law

creating the National Intelligence Service exempted its agents from testifying,

Cruz admitted knowing about the Riocentro bomb before it blew up.

In reality the Riocentro conspiracy involved the entire military terror

apparatus. Press interviews, parliamentary testimony and other statements

by individuals associated with military terror groups–among them ex-officers

and “right-wing militants” linked to the armed forces and the paramilitary

Communist-Hunting Commandos (CCC)–demonstrated that the intended purpose

of the bomb carried by the two officers in their car was a controlled explosion

which would provide cover for bombs placed to explode inside the

auditorium at Riocentro. These were deactivated only after the failure

of the two officers’ mission.

The Riocentro incident was part of a chain of terrorist acts by the

“intelligence community” during this period, including the bombs which

assassinated a secretary at the oppositionist Brazilian Lawyers Guild and

maimed an employee of Rio de Janeiro’s town hall, as well as the series

of bombings of newspaper stands in Rio used to create a panic over “terrorism.”

According to Franco, the army considered blowing up newspaper stands in

Rio again during the 1989 elections. Ten years later, a former member of

the ultra-rightist CCC threatened to blow up a monument to murdered guerrilla

leader Carlos Marighella in São Paulo, saying he “didn’t need help

from Army officers” to do it and demanding the establishment of a monument

to the founder of the bloody São Paulo State Department of Political

and Social Order (DOPS) for “creating the Death Squad which hunted down

and eliminated undesirables and participated in the fight against terrorists”

(Diário do Vale, 5 November 1999).

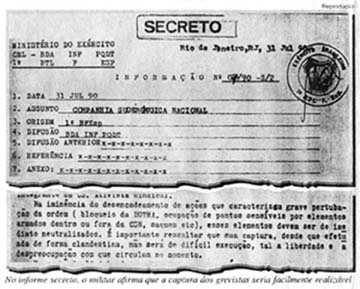

Secret Brazilian Army

document says that "in the event of imminent actions

which would constitute

a grave disturbance of public order" seven "individuals

who stand out for their

radical positions" should be "neutralized immediately."

Death List

Death squads were clearly the inspiration for the plan for capture and

“neutralization” of CSN strikers put forward in 1990 by the commander of

the Special Forces Battalion. In August 1999, the Jornal do Brasil

published an extensive article on this plan, reproducing a secret report

by then-colonel Álvaro Pinheiro which the newspaper obtained from

a former military officer identified as “R.” Saying that he decided to

divulge these secrets because “the Army caused me problems,” R. confirmed

the essential facts of ex-captain Franco’s revelations about the Special

Forces’ terrorist activities and turned over seven army documents, three

of which detailed the movements of Volta Redonda steel workers and visits

by trade unionists and political figures from other cities during the 1990

CSN strike.

The secret report of 31 July 1990 begins with the observation that “July

30 marked the 20th day of the strike at the Companhia Siderúrgica

Nacional” and that “the proposal presented by [CSN] president ROBERTO PROCÓPIO

LIMA NETO...was rejected by the workers.” (Lima Neto was the frontman for

the capitalists most interested in privatizing CSN, and later became a

right-wing politician.)

The report goes on to give detailed information on the speakers and

discussions at union assemblies, stressing disagreements between the most

militant activists and “the ‘moderate’ wing of the Union, whose foremost

representative is union president VAGNER BARCELOS, [who] completely opposes

any kind of radicalization.” (Barcelos was a member of the Democracia Socialista

tendency in the PT, followers of the late pseudo-Trotskyist Ernest Mandel;

he later joined the staff of Cardoso’s minister of sports, Pelé.)

The document highlights “the proposal to blockade the Dutra Highway put

forward...by activists from CONVERGÊNCIA SOCIALISTA (CS) and the

ORGANIZAÇÃO QUARTA INTERNACIONAL (OQI).” It also notes that

the company of Military Police stationed in the city “completely lacks

the credibility and reliability required for reestablishing order when

necessary.”

Then the report gives a list of seven “individuals who stand out for

their radical positions,” providing the full name of each of them, including

Luiz Antônio Vieira Albano, Marcelo Felício, Isaque Fonseca,

Wanderley Barcelos, Nilson Carneiro Sales and Luiz Antônio Coelho

Ferla. One of the first people listed is:

“CARLOS ALEXANDRE HONORATO–‘CEREZO’–Union activist. He is one

of the foremost members of the OQI and a member of the PT of VOLTA REDONDA.”

To be included on this list meant being marked for death, as shown in the

subsequent part of the report, which put forward the plan for eliminating

the activists:

“In the event of imminent actions which would constitute a

grave disturbance of public order (blocking the Dutra highway, occupying

key points inside or outside CSN, looting, etc.), these elements should

be neutralized immediately. It is important to stress that their capture,

which would be carried out in a clandestine fashion, would not be difficult

to carry out, given the freedom and lack of concern with which they circulate

at the present time.”

Jornal do Brasil comments: “One can assume that when [then-colonel]

Álvaro proposed the ‘capture’ and ‘neutralization’ of union leaders,

and sent this suggestion to the higher echelons, his superiors condoned

this. There is no report of him being punished for making an illegal proposal.”

Punished? He was promoted, and today he is a general. With the fake

naïveté of the bourgeois press, JB asks: “What does

it mean to clandestinely capture and neutralize striking workers?”

Everyone knows the answer: in the jargon of the “intelligence community,”

neutralize is one of the many ways of saying kill. In the United

States, the FBI’s “counterintelligence program” COINTELPRO for “neutralizing”

black radicals led to the murder of 38 members of the Black Panther Party

and the death of many other fighters against racist oppression. The police

frame-up against Mumia Abu-Jamal, the radical journalist and former Black

Panther on Pennsylvania’s death row, was the culmination of years of persecution

against him under this same secret police program. In fighting to mobilize

the power of the working class to free Jamal, we are fighting against capitalist

state terror here in Brazil as well, and all over the world.

Marcos de Oliveira/Imagens da Terra

Assembly of metal workers

during 31-day strike, July 1990.

The 1990 Steel Strike

In his interview with The Internationalist, comrade Cerezo recalls

that “we suspected at the time, but now the revelations confirm the fact

that they really sought to capture and neutralize part of the strike committee”

in 1990. The 1990 strike was one of the most important struggles in the

period preceding the “auction”–in reality an outright giveaway–of CSN.

The steel company’s privatization followed a plan originally presented

by the government of Fernando Collor de Melo, which soon became an international

symbol of presidential corruption; it was carried through by president

Itamar Franco with the support of Rio governor Leonel Brizola. (Both Franco

and Brizola are now “heroes” of Lula’s popular front.)

“The strike began because CSN owed each steel worker four to six months’

back wages,” Cerezo notes, “under the pretext that the company was in a

financial crisis and was going bankrupt.” Meanwhile, CSN’s standard practice

over the course of many years was to furnish steel to large Brazilian and

international corporations at prices well below the cost of production.

“So a struggle broke out to demand the back wages and also to oppose privatization

and win back the jobs of a number of workers who had been fired.”

Cerezo continues:

“It’s important to point out that this struggle occurred immediately

after the election of Collor, who openly said CSN might be shut down....

One of the ways Collor’s attack was expressed was by not paying the company’s

debt to the workers and to make a list of people to be laid off in preparation

for the privatization. Collor sent his frontman Procópio Lima Neto

to carry out this mission. Lima Neto was put in place by the Monteiro Aranha

group, a group of businessmen known for living off of corruption, which

was getting ready to take a big slice of the pie when state-owned industries

were privatized. They served as a front for imperialist companies which

were constantly exercising pressure and various forms of blackmail as pioneers

in the push for privatization and mass layoffs at CSN and other state enterprises.

“So the strike was against all of this. It was the hostile reception

the workers gave to this frontman for imperialism and Brazilian big capital.”

For his part, Lima Neto did not bother to conceal his contempt and hatred

for the workers, including in his references to the killing of the three

strikers in 1988. When questioned about his decision not to ask that troops

be sent against the strikers in 1990, he responded: “I’m not going to give

them any more corpses.”

In fighting for this strike, Cerezo and the Luta Metalúrgica

group (predecessor of today’s LQB), together with other activists, had

to wage a major struggle against the union leadership: “The union bureaucracy

reacted by trying to put obstacles in the way of a strike.” Led by the

Mandelite Vagner Barcelos, they argued that the company’s crisis made it

impossible to call a strike and that the CUT labor federation should avoid

being accused of instigating “chaos.”

The 31-day strike was preceded by a plant occupation on 11 May 1990.

At the beginning of the occupation a contingent of 8,000 workers entered

the plant singing the Internationale, the revolutionary working-class anthem

composed during the Paris Commune. Cerezo recalls: “In several other marches

and mass meetings the workers sang the Internationale. It was exciting

and quite beautiful, and showed the radicalism of this struggle. The workers

were already in the habit of doing this, because the union sound truck

always used to play a tape of the Internationale, and sometimes the words

were passed out to the workers so they could sing the lyrics.”

João Ripper/Imagens da Terra

Demonstration by railroad

workers against mass layoffs by the National Steel Company,

May 1990.

At a mass union meeting held during the plant occupation, comrade Cerezo

put forward the proposal to maintain and intensify the mobilization and

clear a path of struggle for the entire workers movement. Within a short

time there would be strikes by the Ford workers and electrical workers;

millions of working people throughout Brazil wanted to resist layoffs and

the brutal slashing of real wages. But the spokesmen for the union bureaucracy

succeeded in pressuring the CSN workers into temporarily suspending the

plant occupation while they presented various reformist schemes for fixing

up the company’s financial situation.

Fighting against this sell-out perspective, in July “we called another

mass meeting, and this time the workers voted to go on strike,” Cerezo

remembers. “The 31-day strike was characterized by a high level of mobilization,

with the participation of 28,000 to 30,000 workers, who decided to face

this situation head-on and refused to be intimidated by the murder of William,

Valmir and Barroso in the previous strike two years earlier.”

Yet despite the CSN workers’ enthusiasm and the potential to broaden

the struggle, in the midst of the strike there was an attempt at reformist

sabotage led by representatives of Convergência Socialista (predecessor

of today’s PSTU [United Socialist Workers Party]), the followers of the

late Argentine pseudo-Trotskyist Nahuel Moreno. Cerezo explains:

“In the middle of the strike, Convergência proposed that

CSN’s debt to the steel workers be turned into debentures, a kind of bonds

which the workers would hold while they waited for a supposed improvement

in CSN’s situation, which meant that Convergência had swallowed the

company’s whole line about the crisis it was in. It was clear that the

capitalists were saying this to gouge and lay off the workers. But these

people created this illusion about swapping the four to six months’ back

wages for bonds, debentures and other paper issued by the government. This

was how the way was cleared for privatizing CSN. The proposal came from

Convergência, and the Mandelites, the Catholic left, the PDT–all

of them part of the union executive board–accepted it. This was a heavy

blow which we fought against at the time.”

In reality, he continues, “this was the foundation stone for the ‘independent

CUT Investment Club’ created two years later” by the popular-frontists

to grease the skids for privatizing the plant outright. “It was class collaboration

under the guise that CSN was in crisis, that it was unsustainable, so they

created ‘leftist’ phrases about the debt being paid when the company recovered....

The Morenoites were the pioneers of parceria” (“partnership,” Força

Sindical’s slogan for union-company collaboration in a privatized CSN).

The same reformist logic later led the Morenoites to participate directly

in the Frente Brasil Popular, the class-collaborationist alliance between

bourgeois politicians and Lula’s PT.

The entire course of this struggle, in which the main protagonists included

militants of three different tendencies which identified themselves (falsely)

as Trotskyists, underlines that the fight for an authentic class-struggle

leadership is at the same time the struggle for genuine Trotskyism. This

is the task undertaken by the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista do Brasil.

The Bureaucracy’s Three Nooses and Lima

Neto’s Attack

Referring to this betrayal by Convergência, Cerezo says: “Even

so, with their open class collaboration, they were unable to put a stop

to the strike. The strike continued for another 15 days.” He continues:

“At a certain point the bureaucrats decided they didn’t want

me to speak in one of the union assemblies, and they used a squad of violent

goons to try to stop me by force. I broke through the goon squad, got up

on the sound truck and said the only way I would agree not to speak was

if the assembly voted not to let me. It was a meeting of about 5,000 workers.

While a union bureaucrat tried to take the microphone away from me, the

workers voted massively for me to speak. The bureaucrat was defeated and

had to let me use the mike. I said that both the bureaucracy and Convergência

were creating obstacles aimed at defeating our strike.

“In the next days the union bureaucracy put up three nooses, threatening

to hang me, together with Nilson and another Luta Metalúrgica activist

called Boquinha–in other words, to lynch us. This was about 15 days into

the strike, and they put up a big beam with the three nooses and signs

saying they were for the three of us. The ones who organized this were

a bureaucrat from the PDT together with the Mandelite Vagner Barcelos.

This was directly related to them trying to stop us from speaking and their

attempts to put an end to the strike.”

But Cerezo says “we didn’t let ourselves be intimidated, we managed to

speak in the assemblies and we put forward the proposal for the strike

to be extended, to occupy the Dutra Highway and transmit our struggle to

other workers, and for us to join together with the strike which had broken

out at Ford, and with the electrical workers’ strike. The workers supported

this proposal.”

It was these debates which proved so worrisome to the officers and spies

of the Special Forces Battalion, as shown in the recently published documents.

It was against the plan to extend the strike, in particular, that they

proposed the capture and neutralization of strike activists.

When

the union bureaucrats failed to prevent Cerezo from speaking, Procópio

Lima Neto attacked him in the company’s Informativo newsletter,

saying that Cerezo was putting forward dangerous proposals and that the

strike “is being used for political purposes.” In an article titled “Our

Answer to Procópio,” the Luta Metalúrgica bulletin

(August 1990) responded: When

the union bureaucrats failed to prevent Cerezo from speaking, Procópio

Lima Neto attacked him in the company’s Informativo newsletter,

saying that Cerezo was putting forward dangerous proposals and that the

strike “is being used for political purposes.” In an article titled “Our

Answer to Procópio,” the Luta Metalúrgica bulletin

(August 1990) responded:

“YES, OUR STRIKE IS POLITICAL. It is the politics of defending

the workers massacred by savage wage-cutting.... It is against your

politics of privatization and draining CSN to pay off the foreign debt.

Our strike is against your politics and that of the government you represent.”

The slogans Luta Metalúrgica put forward during the strike also

included opening the company’s books to inspection by the workers, cutting

the workweek with no loss in pay, and workers control of production.

Strikebreaking Role of the Popular Front

Cerezo recounts that despite the workers’ support for the proposal to

extend the strike, “the bureaucracy did not abide by the decision and asked

Lula to come to Volta Redonda.”

“So Lula traveled to Volta Redonda and had a meeting with activists,

excluding the Luta Metalúrgica members such as myself, Nilson, Boquinha.

What he said was that we were a danger. And Lula said the strike should

end and that the workers should not follow the proposals put forward by

these radicals like Cerezo, Nilson, Boquinha, etc.

“From that point on the union bureaucracy dealt heavy blows to the

strike until it was finally able to defeat the strike, without holding

a union assembly, in a treacherous fashion, and with various people being

fired. Approximately three days after Lula came to town, the strike ended.

It was a major betrayal against the workers.”

Cerezo explains that this betrayal was the direct application of the politics

of the popular front. While the PT emerged from the wave of tumultuous

workers struggles in the late ’70s and early ’80s, Lula’s party always

had a reformist program. Evolving further to the right, however, it abandoned

its original slogan of “Workers vote for workers” and decided to crystallize

the program of class collaboration by forming the Frente Brasil Popular

with bourgeois politicians for the 1989 presidential elections.

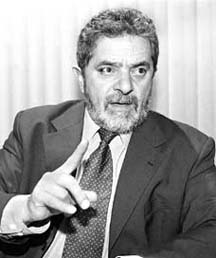

La Jornada

PT leader Luiz Inácio

Lula da Silva went to

Volta Redonda in August

1990 to stop steel

strike and isolate militant

leaders like Cerezo.

Cerezo, who was elected president of the Volta Redonda PT in 1988, voted

against the Frente Brasil Popular at the PT’s Sixth Conference, held in

São Paulo in June 1989. His position was approved at a plenary meeting

of 290 members of the Volta Redonda PT, against the violent opposition

of Convergência Socialista in particular. It was in this context

that Cerezo and other Luta Metalúrgica militants joined Causa Operária

(formally called the OQI), in the belief that it represented a proletarian

opposition to class collaboration, although in reality Causa Operária

voted for Lula, candidate of the popular front.

Cerezo explains that “the popular front was in high gear”:

“So the formation of the popular front and the betrayal of

the 1990 strike are two directly related events.

“The leftists who were active against us in the union were part of

the popular front. In the period immediately before the strike, the Mandelites,

who at that time were leading the union, were even calling for a government

of Lula and Brizola. In other words, they were proposing an even more right-wing

popular front, which would include not only Arraes’ PSB but also the PDT.

This was actually carried out later [for the 1998 elections].”

A year after the strike, the PT began a purge against its left wing, beginning

with Causa Operária. The first targets were the comrades of Luta

Metalúrgica in Volta Redonda. In a document written in 1991 on the

eve of the PT’s First Congress, Cerezo wrote that this “witch hunt” was

launched “at a time when the threat is looming that CSN will be privatized,

bringing mass layoffs,” after the city’s proletariat had in effect gone

up against “the ‘National Security Area’ and courageously confronted the

armed fist of the bourgeoisie–the army.” He warned that privatization and

repression were “the solution the popular front is preparing for the population

of Volta Redonda.”

The reformist leaders soon gave their response, as Cerezo recounts in

the interview: “Since they were unable to achieve their objective through

a vote in Volta Redonda, they sent João Machado, a Mandelite who

was part of the national leadership of the PT; Jorge Bitar from the Rio

PT, who is now the secretary of planning under Rio state governor Garotinho;

Dodora from Força Socialista (another tendency in the PT), the leader

of the teachers union in Volta Redonda; Vagner Barcelos, and Ernesto Braga,

today the national president of the PT. They put together a special commission

to intervene in the Volta Redonda PT in order to expel us.” (The name of

the Mandelite tendency in the PT is Democracia Socialista, which as it

turns out translates into “democracy” for the bourgeoisie and expulsion

for class-struggle militants.) The LM comrades showed up at a PT local

meeting and found a sheet posted on the wall announcing that they had been

“excluded” from the party.

For the reformist PT leaders, these expulsions were the counterpart

of the process of deepening class collaboration, as shown for example by

the PT’s and CUT’s participation in “chambers of industry” with the employers

and the Collor government; the presence of prominent PTer Erundinha in

president Itamar Franco’s cabinet; the PT’s participation in state and

municipal governments run by the PDT, Cardoso’s PSDB, the PMDB (Party of

the Brazilian Democratic Movement), etc. But even where the PT governed

alone, its policies were no different from those put forward by these bourgeois

parties.

Against the reformist PT and the bourgeois popular front, the comrades

of Luta Metalúrgica continued the struggle for the revolutionary

independence of the working class, which later led them to clash with Causa

Operária’s political line. As Cerezo points out in the interview

with The Internationalist:

“Causa Operária said in 1989 that it was against the

popular front. But from ’89 to ’94, when we were in CO, what they really

did was tail Lula and the PT.... In all the elections they came out for

supporting and voting for Lula.

“During the 1990 strike their publications were militant in form, but

when it came to the revolutionary program and important issues like the

woman question, the black question, the defense of homosexuals, they had

absolutely nothing to say.

“So what we did, knowing what the popular front was about, was to try

to look more deeply into the program, and we found there was an immense

vacuum in their program. So we decided to fight on the black question,

the woman question, the popular front, putting forward documents in 1994

stating our repudiation of these politics of class collaboration and of

ignoring the revolutionary struggle against special oppression.”

Cerezo stresses:

“Our line of combating class collaboration means no vote to

any candidate of the popular front. We have seen and lived what the popular

front really means and how it is the enemy of the working class. On the

basis of these experiences and lessons, our group went through a revolutionary

evolution. We fight for a revolutionary workers party, a Trotskyist party.

In 1996 we formed the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista do Brasil, which two

years later was one of the founding sections of the League for the Fourth

International.”

Vanguarda Operária

Cerezo pointing to poster

showing stand-off between the army and workers in

1988 steel strike which

won the six-hour day. Poster says: "No to Privatization

of CSN. For Workers Control

of Production."

The Struggle Continues: Forge a Revolutionary

Workers Party!

Those who fought against bourgeois state repression, against the popular

front, for the intransigent defense of the workers’ rights, continue fighting

for the interests of all the oppressed and exploited, the struggle for

international socialist revolution. They remained at their posts, and call

on new forces to join the struggle.

Having denounced the “armed fist of the bourgeoisie” which repressed

strikers and prepared a hit list for assassinations, in 1996 the LQB carried

out the struggle for the expulsion of the municipal guardas from

the Volta Redonda municipal workers union (SFPMVR), which was voted by

the union assembly of 25 July 1996. The following year, the LQB and the

Comitê de Luta Classista (CLC–Class Struggle Caucus) denounced support

by the opportunist “left” to “strikes” by the Military Police, stressing

that police are professionals of bourgeois repression who must be expelled

from all unions and from the CUT. We have defended the class-struggle program

against the repression, physical attacks and slanders of the pro-police

provocateurs of Artur Fernandes’ clique (as well as their “left” apologists,

among them the Liga Bolchevique Internacionalista and its “Revolutionary

Trade-Union Tendency”), imposed by the bourgeois courts against the will

of the workers so as to masquerade as the SFPMVR. And we have defended

this program against the capitalist state, which even ordered the “search

and seizure” of our leaflets in September 1997.

In the 1998 elections we warned that the “Broad Front” of Lula and Brizola

bound the exploited hand and foot in the face of the onslaught by Cardoso

and the IMF; and as an expression of proletarian opposition to the popular

front, we called for casting a blank ballot. Against class collaboration,

we call for workers mobilizations to defeat the starvation plans of the

Brazilian bourgeoisie and their imperialist senior partners.

As part of the internationalist struggle against black oppression, we

have succeeded in getting various unions to begin mobilizing in strikes

and work stoppages to demand immediate freedom for Mumia Abu-Jamal, a first

step that must be extended and intensified. The struggle for black liberation

through socialist revolution “is a basic and strategic question as part

of the program of permanent revolution in Brazil,” observes Cerezo, which

manifests itself in many different issues, “from the struggle against the

murder of street children and forced sterilization of black women to the

question of leukopenia. [Leukopenia, the drastic reduction in white blood

cells caused by exposure to the benzene gas produced by steel plants’ coke

ovens, affects many workers in the Volta Redonda area.] Long before the

bourgeois press finally decided leukopenia was newsworthy, back in 1993

at the first “CUT anti-racist seminar” Luta Metalúrgica was the

first to denounce CSN’s racist practice of characterizing this as a “black

disease.”

Today, when many leukopenia sufferers are fighting for their rights,

the company insists that leukopenia “is not considered an illness according

to the criteria of the Ministry of Health” (O Estado de S. Paulo, 3

December 1999). At the same, in yet another example of the phony character

of the bourgeoisie’s “environmental laws,” a recent press report stated

that “the index of benzene in the air of Volta Redonda is 80 times greater

than the level allowed by legislation.”

The great themes and issues of past struggles have a very concrete expression

today in Brazil and at CSN. Cerezo states in the interview:

“We want to fight against the return of the 8-hour work shift,

together with fighting this attack on workers who suffer from leukopenia.

CSN wants to destroy the victory won by the workers in the 1988 strike,

when we won the six-hour day. Together with firings of people with leukopenia,

they want to increase the workday and carry out mass layoffs. We put out

a bulletin on this question, calling for a militant strike not only at

CSN but at other steel plants as well, to fight CSN’s policy of wage-slashing,

layoffs and racism.”

The Class Struggle Caucus bulletin (19 May 1999) emphasizes that this means

shutting down Volta Redonda completely and extending the strike to the

other sectors of the empire controlled by CSN (Vale do Rio Doce mines,

the Light electric company, etc.). The slogans it puts forward include

an end to layoffs and the brutal speed of production at the plant; cutting

the workweek with no loss in pay, dividing available work among those presently

employed and unemployed; opening jobs to women and establishing high-quality

24-hour child-care centers. The bulletin points out:

“In a situation where the bosses try to pit Brazilian steel

workers against the workers of other countries, we must declare our solidarity

with our class brothers and sisters by making real the motto of the workers

movement: ‘Workers of all countries, unite!... Forge a class-struggle leadership,

cohered in the world party of socialist revolution, a reforged Fourth International,

to lead the struggle for power for the proletariat and all the oppressed!”

Cerezo ended the interview by noting: “Young people in particular are key

to the revolution. So we want them to know about the struggle in order

to draw lessons from the defeats and the victories, to learn, and above

all to join the ranks of the struggle and the revolution. Against every

obstacle we continue the fight, and we invite the workers to join us.”

n |