December 2007

and Indian Government

Soldiers approach a barricade of striking oil workers in Orellana province under the government of

Alfredo Palacio, in March 2006. Today the equally capitalist government of Rafael Correa strikes at

the peasants of Orellana. (Foto: Dolores Ochoa R./AP)

For an Andean Federation of Workers Republics!

Over the last two decades,

Ecuador has found itself in an almost constant state of upheaval and

revolt:

workers and peasants struggles of the 1980s, indigenous uprisings of

the ’90s

and so far in this century the overthrow of presidents Mahuad (2000), Noboa (2003) and Gutiérrez

(2005) by popular mobilizations.

Yet

after all this, practically nothing has changed in the direction the

country is

headed. It is still subject to the dictates of Yankee imperialism, the

dollarization of the economy, the U.S. Southern Command’s occupation of

the

Manta Air Base, the domination of the multinational oil companies over

the

Amazon regions, the control of politics by traditional oligarchic

clans, the

omnipresent poverty and the forced emigration of over 10 percent of the

national population. By all accounts, Ecuador needs a revolution. But

the

question is posed, what kind of revolution?

The current president, Rafael Correa, a bourgeois populist, has proclaimed

himself a

“Christian humanist of the left” while he declares a “civic revolution”

to

improve public morality and arrive at “profound, radical and rapid

change of

the prevailing political, economic and social conditions.” Exactly what

this

change consists of is not something he has addressed in detail. On the

other

hand, he ferociously opposes any class actions, particularly

the

struggle for a workers revolution to bring down the capitalist

system. But this is exactly what Ecuador requires: a struggle for a

revolutionary workers, peasants and Indian government, which would join

with

the neighboring countries in an Andean federation of workers republics,

which

in turn would be part of a Socialist United States of Latin America.

Without

this proletarian internationalist program, the infernal cycle of

bourgeois

military and “democratic” governments will continue, spelling unending

poverty

for working people.

After the expulsion of the

self-styled “dictocrat” Lucio Gutiérrez

from the Palacio de

Carondelet (Ecuador’s

presidential palace) in the so-called “revolt of the forajidos (outlaws)”

in April 2005, the government of his vice president Alfredo Palacio González carried on with the same policies,

implementing the

measures dictated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and

negotiating a

free trade agreement with the United States. Blocked by the opposition

headed

by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities and Peoples of Ecuador

(CONAIE by its Spanish initials) and other Indian

organizations through mass demonstrations and highway blockades, Palacio decreed a state of emergency in March 2006.

Finally,

in the November 2006 presidential elections, the economist Correa was elected, owing his victory to the

support of

various indigenous and leftist organizations in the second round of

voting, on

the base of his popular-frontist program.

So strong was the

antediluvian right wing opposition to Correa

that many reformist leftists, trade-unionists and Indian activists at

first

gave their support to the new president. Without a murmur of protest,

they

accepted that there would be no cushy ministerial posts for them in the

new

cabinet, as there had been in the government of Gutiérrez: they also submitted when Correa refused to place their names on the

electoral slate

of his PAIS (“Exalted and Sovereign Fatherland,” which

spells

“Nation” in Spanish) movement. Nevertheless, at the same time as he has

distanced himself from the White House and Washington’s financial

institutions

and drawn closer to nationalist forces and regimes, in domestic affairs

the

balance sheet of eleven months of Correa’s

“center-left” government is one of concessions to “modern”

right-wingers and

violent attacks against leftist demonstrations. Now with the defeat of Hugo Chávez in the Venezuelan constitutional referendum,

Correa’s shift to the right will proceed at an

accelerated

pace.

There is point in accusing Correa of betrayal: he has always been faithful to

his bourgeois

program. Responsibility for the current political state of affairs for

the

Ecuadorian workers, peasants and indigenous peoples falls on a left

that time

and again has sought to tie itself to one or another capitalist

politician, military figure or economist, sacrificing the working class

in the

interests of an alliance for class collaboration, a “popular front.”

From the

outset, we Trotskyists of the League for the Fourth International

warned against

alliances between the indigenous and leftist movement and Colonel

Gutiérrez and

his military lodge1,

which at

first pretended to be leftist but is now universally acknowledged as

ultra-rightist; we warned against placing confidence in the “outlaws,”

a

bourgeois and potentially rightist movement2.

Now, once again, we state that fundamental task remains the

construction of a revolutionary

workers party free of any political ties to the bourgeoisie.

Constituent Assembly

and

Repression:

The Correa

Government Attacks the People of the Amazon

Doubtless, with his leftish

rhetoric Correa’s election awakened great hopes among the impoverished

working

masses, as well as in the middle layers (the petty bourgeoisie), who

were sick

and tired of the corrupt governments of the traditional Ecuadorian

parties, the

so-called partidocracia. When he was sworn in as president in

mid-January, Correa pronounced himself to be a partisan of “21st

century

socialism,” favoring “Bolivarian” regional integration with Hugo

Chávez’ Venezuela

and Evo Morales’ Bolivia, and announced the imminent calling of a

Constituent

Assembly. His PAIS movement did not run any candidates for the

disgraced

Congress, infamous as a sordid den of oligarchs and thieves, intending

instead

to shut it down with the forthcoming Assembly. Immediately a hue and

cry arose

from the parliamentary majority – headed by Álvaro Noboa’s PRIAN

(National

Action and Institutional Renovation Party), Jaime Nabot’s PSC (Social

Christian

Party), and Lucio Gutiérrez’s PSP (Patriotic Society Party) –

amplified by the

big media outlets, labeling the Correa government a “dictatorship.”

But then something

unexpected occurred. Before the Congressional majority could reject his

plans

for a Constituent Assembly, the country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal

stepped in

on Correa’s side. When the infuriated parliamentary deputies voted to

depose

the head of the Tribunal, a traditional right-winger, the court decreed

the

expulsion of 57 deputies from Congress. These were later replaced by

deputies

from the same parties, who approved the referendum for a Constituent

Assembly.

The population responded in favor of convoking the Assembly with a

landslide

majority, 81 percent of the vote. Once again, when deputies to the

Assembly

were elected on September 30, the candidates of the ruling PAIS

alliance won 80

of the 130 seats. With this strong popular backing, Correa announced

that

henceforth, Ecuador would take 99 percent of excess profits from the

sale of

oil by foreign petroleum companies.

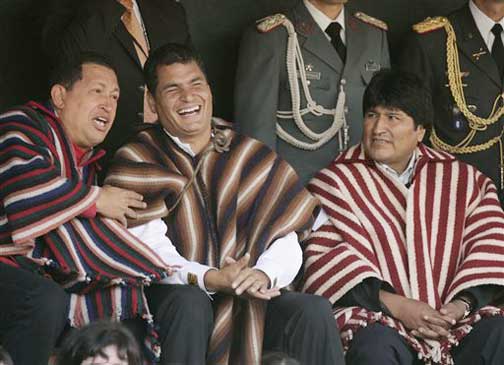

Bourgeois nationalist

presidents of the region. From the left: Hugo Chávez

(Venezuela), Rafael Correa (Ecuador),

Evo Morales (Bolivia). For an Andean federation of workers republics!

Bourgeois nationalist

presidents of the region. From the left: Hugo Chávez

(Venezuela), Rafael Correa (Ecuador),

Evo Morales (Bolivia). For an Andean federation of workers republics!

(Photo: Fernando Llano/AP)

Nevertheless, on November

30, the very day that the Constituyente was inaugurated in

Montecristi

(in the coastal province of Manabí) – the birthplace of Eloy

Alfaro, champion

of the 19th century Liberal Revolution – a brutal military crackdown

was

unleashed on the parish of Dayuma, in the Amazonian province of

Orellana. The

Amazonian rebels had the temerity to block a road, resulting in

shutting down

production at an oil well. For this action, the President labeled them

“terrorists” and “mafiosi.” Correa declared a state of emergency in the

region.

The local population is demanding implementation of an agreement signed

over

five years ago, promising them a paved road, electric power and jobs,

“but

instead of asphalt, the people of Dayuma were given tear gas, gunshots,

beatings and prison,” says a December 5 bulletin of the Coordinadora de

Movimientos Sociales (Coordinating Committee of Social Movements).

News of the military attack

produced consternation across the whole country. Reports from Dayuma

speak of

one peasant shot to death, some 27 people detained, and others

“disappeared.”

The great majority of the detainees are peasants, who emphasize that

they voted

for Correa in the elections,. They were dragged from their homes,

barefoot,

hands tied, airlifted by helicopter to the cantonal, Coca, held

incommunicado

and subjected to “robust” interrogation, as the thugs of

Guantánamo put it (all

the Dayuma detainees bear marks of torture). Some 22 people are still

being

held captive, among them, the prefect of the canton, Guadalupe Llori,

who was

immediately transferred to the national capital Quito, supposedly “for

her own

protection.” There is also an arrest warrant for the woman mayor of

Coca. The

workers movement must demand the immediate release of all the detainees.

But what’s most significant

about this incident is what it reveals about the character of the

government

itself. It’s not the first time Correa has moved against protesters for

obstructing oil production. At the beginning of March, peasants of the

same Orellana

province occupied the installations of Bloque Azul, which was being

operated

(illegally, according to the peasants) by the former Brazilian state

oil

company, Petrobras. (Since being denationalized by the government of

Lula da

Silva, the majority of Petrobras stock is held privately by Wall Street

investors.) Five local residents were wounded in the ensuing

repression. “I

can’t comprehend how, under this government, the same forms of

repression are

being repeated as under the neoliberal regimes, and how the army has

been

converted into a gendarme of the petroleum multinationals,” commented

Fernando

Villavicencio of the Movimiento Gente Común (Movement of the

Common People).

But they were. And now it is being repeated.

First of all, we must

reject the possibility it’s all a big mistake, that the president was

“misinformed,” as some pro-government pseudo-leftists make believe.

When

deputies to the Constituent Assembly announced that they would address

the

issue of Dayuma, Correa himself threatened that if the Assembly, in

which his

partisans hold a majority, took up the case, he would resign. At a

press

conference on the capital’s “Mariscal Sucre” Airbase, he bellowed “the

anarchy

in Orellana has ended.” It is “time to restore order,” he added,

insisting that

“those bands of mafiosi have met their end, the sabotage, the

blackmail, is

over.” Besides calling the peasant fighters and Amazonian ecologists

“terrorists,” even speculating about an intrusion by the FARC (the

Communist

Party-led Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), he insisted that the

detainees remain in prison. So the question is, why is he demonizing

and

repressing his own followers?

The key is that Correa is a

nationalist, a populist to be sure, but bourgeois above all.

In place of

the “neoliberal” policies of the “Washington consensus,” of the

globalization

that has resulted in the privatization of many social services and

large

industrial sectors in Latin America and the takeover of many companies

by

imperialist conglomerates, Ecuador’s economist-president is a partisan

of the

“developmentalist” policies associated with the figure of Raúl

Prebisch

(1901-1985) and his Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA) who

promoted a

process of industrialization through “import substitution” on the

continent

from the 1950s through the ’80s. Today, leftist types criticize

neoliberalism,

but not capitalism, implying that they are looking for another

capitalist “model,” particularly the one pushed by Correa.

The Ecuadorian president

has fulminated against imperialism and ordered reprisals against

companies that

damage the country’s sovereignty. When the representative of the World

Bank

criticized his economic policy, Correa expelled him. When the Pentagon

would

not accept the annulment of its contract for occupation of the airbase

and port

of Manta by forces of the Southern Command, which uses it as a base for

counterinsurgency operations in Colombia, Correa reiterated that he

would not

renew the contract, unless the U.S. gave Ecuador a military base in

Miami in

order to keep an eye on the military activities of the great power of

the

north. When Occidental Petroleum – known as la Oxy – which for

many

years dominated the production of black gold in the Amazon region,

transferred

the oil production rights for several tracts to a Canadian firm without

the

Ecuadorian government’s permission, Correa canceled their entire

contract. Many

leftists took heart to see a president who did not bow and scrape

before the

imperialist master.

Nevertheless, to hope for a

“sovereign path of development” together with “Third World” capitalist

regimes

like Brazil or Chile, and with the Chinese bureaucratically deformed

workers

state, will not favor the Ecuadorian workers. Correa’s government could

indeed

build a paved highway in the Amazon, but not for the benefit of the

region’s

people. It would be part of his project to build a land route between

the port

of Manta and the Brazilian Amazon to facilitate exports to China. In

fact, the

repression in Dayuma followed right after the president’s return from

his tour

of the Far East, and just before his meeting with representatives of

Petrobras

to renegotiate their oil production contracts. He sought to show, by

military

force, that he was capable of enforcing his contractual commitments.

Spiced up with “socialist”

phraseology, and due to his frictions with the predatory policies of

U.S.

imperialism, Correa’s cause has been embraced with gusto by

opportunists of the

reformist left. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these gentlemen

have

abandoned all confidence in socialist revolution (if they ever had any)

to

place their hopes in bourgeois nationalists like Chávez, Morales

or Correa, and

even in “neoliberals with a human face” like Mexico’s Andrés

Manuel López

Obrador. In the Venezuelan case, this is accompanied by the caudillo’s

passing

fancy for the historical figure and some of the phrases (but not for

his

program of international proletarian revolution) of the great Russian

revolutionary and founder of the Fourth International, Leon Trotsky.

But the

“developmentalist model” of economics is no less capitalist than the

“neoliberal” model. And in the class struggle in his own country,

Correa is

ready to strike against the workers as forcefully as any of the satraps

of

George Bush – as the courageous peasants of Dayuma have just

experienced.

Fight for Permanent

Revolution – Forward on the Path of Lenin and Trotsky!

In August Rafael Correa

called together a conference in Quito on “the socialisms of the 21st

century,”

moderated by none other than his minister of “defense” (that is, of the

bourgeois armed forces), Lorena Escuerdo, whose predecessor Guadalupe

Larriva

died in a suspicious airplane “accident.” It’s a curious “socialist”

regime

that dispatches troops to Haiti (the new Ecuadorian contingent consists

of 60

soldiers and four officers) under Brazilian and Chilean command as part

of a

colonial occupation that is barely disguised by the blue helmets of the

United

Nations, freeing up the U.S. expeditionary force for the occupation of

Iraq.

Trotskyists fight to drive out the mercenary occupation forces from

Haiti,

including the Ecuadorian troops.

The

undersecretary of war in the government of Rafael Correa greets

Ecuadorian troops, part of the forces occupying Haiti under the aegis

of the United Nations. Trotskyists fight to drive out the mercenary

occupation forces.

The

undersecretary of war in the government of Rafael Correa greets

Ecuadorian troops, part of the forces occupying Haiti under the aegis

of the United Nations. Trotskyists fight to drive out the mercenary

occupation forces.

(Photo: Ministerio de Defensa

Nacional)

In his lecture at the Quito

conference, the Ecuadorian president followed the line drawn by his

Venezuelan

counterpart, declaring that “21st century socialism is a work in

progress and

calling for it to be permanent,” as an official report of the

presidential

office put it. In order to avoid any confusion, Correa underlined that

for this

“socialism,” which he calls an “authentic intellectual product” of

Latin

America, “class struggle and violent conflict are impermissible in the

21st

century.” He also maintained that “the elimination of private property

is

intolerable,” and argued for “the democratization – but not necessarily

state

ownership – of the means of production” seeking to “live well, in

harmony with

the natural environment, and with regional, ethnic, and gender equity.”

For his

part, the “leftist” president of the Constituent Assembly, Alberto

Acosta, vows

that “private property is guaranteed” (El Comercio, 5 December

2007).

So here we have the noble

harmonious vision that leads the “socialist,” the “Christian humanist

and

leftist” president, to imprison Amazonian Indians and women protesting

against

the ravages caused by the brutal methods of oil drilling on their

lands! But

Correa is not alone. The whole spectrum of reformist leftists, from the

petrified Stalinists of the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party of Ecuador

(PCMLE)

to post-modern, post-Marxist academics, have traded in their socialist

rhetoric

for talk of “democratic revolution.” Thus, far from calling for a

socialist

revolution, with power passing into the hands of workers’ and peasants’

soviets, today they seek to inaugurate “participatory democracy” by

means of a Constituent

Assembly. For example, the North American socialist academic Roger

Burbach

writes:

“With the collapse

of

Marxism-Leninism and its central tenet that the bourgeois state can be

transformed only through revolution and seizing state power, the

constituent

assemblies in South America raise important theoretical and strategic

questions.”

–R. Burbach.

“Ecuador’s

Popular Revolt”. NACLA Report on the Americas,

September-October 2007

The “democratic” slogan for

the Constituent Assembly, which is in vogue all over the continent,

cannot

avoid the inevitable class conflict. Talk of “refounding”

these

thoroughly capitalist countries without bringing down the rule of

capital is a

fraud3.

The only way to liberate the working masses from poverty and emancipate

indigenous peoples from their age-old oppression, along with women,

blacks and

other sectors victimized by capitalism, is through socialist revolution4.

In this struggle, the proletariat must serve as a tribune of the

people, as

Lenin indicated: it must put itself at the head of and be the defender

of all

the oppressed and exploited. And furthermore as Trotsky emphasized in

his

theory and program of permanent revolution, in the epoch of

imperialism

none of the great tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution can be

realized

short of the conquest of power by the working class, which will be

obliged,

simply in order to maintain its rule of soviet democracy (the

dictatorship of

the proletariat), to take up socialist tasks and extend the revolution

to the

heart of imperialism.

Ever since the ’70s we have

experienced the gravely restricted bourgeois democracy that is the only

sort of

“democracy” there can be in semi- or neocolonial countries like

Ecuador. The

despised “partidocracia” that held sway over the last three decades

replaced

the bloody military regimes that preceded it. Governments of both

varieties

fully complied with the dictates of imperialism. If today the

government of

Ecuador allies itself with Lula’s Brazil, Morales’ Bolivia,

Chávez’ Venezuela,

and Néstor Kirchner’s Argentina, the result will be no

different, since all of

these are capitalist regimes. The current Ecuadorian situation

is even

more acute than the others. How will Correa’s government carry out

“developmentalist” economic policies when the Ecuadorian currency is

the U.S.

dollar? At any moment the imperialists could flood Ecuador with

greenbacks and

set off skyrocketing inflation.

As we have pointed out, the

government of Rafael Correa only wants to defend its own bourgeois

class

interests. If it must repress the Amazonian people of Dayuma to open

the

“Multi-Modal Manta-Manaos Corridor,” or shoot down peasant protesters

in order

to give preferential treatment to Petrobras in the Bloque Palo Azul

oilfields,

well, that’s capitalism for you. The real obstacle to a

successful

struggle against the enemy – the bourgeois governments, whether

of the

rightist oligarchy or the populist left – is found in the reformist

pseudo-socialist and indigenous leadership. And what’s at issue is not

a

misguided strategy. With their program of class collaboration, they are

easy

prey for the tricks of the “neoliberals.” The economist Pablo

Dávalos showed

how imperialist agencies have literally bought these sell-out leaders:

“The World Bank

came to

create projects specifically for those social actors who could become

key

political leaders in the resistance to neoliberalism. The intention of

these

projects was to politically neutralize them, destroy their

organizational

capacity, and corrupt their leadership and political cadres, converting

them

into technocrats of development. For the indigenous movement, the World

Bank

created the Project for the Development of the Indigenous and Black

Peoples of

Ecuador (PRODEPINE), for the peasant and rural sectors it created the

Project

for the Reduction of Poverty and Local Rural Development (PROLOCAL),

for the

women’s movement it applied the Program of Gender and Innovation for

Latin

America (PROGENIAL).”

–Pablo

Dávalos. “La

politica del gatopardo”. América Latina en Movimiento

No. 423 (Ecuador

en tiempos de cambio), 20 August 2007

And for the

labor movement and left-wing political parties (the PCMLE and

Pachakutik, the

party of the indigenous movement) there were the lures of ministerial

posts

with their juicy fringe benefits in the Gutiérrez government,

until popular

rebellion forced them to withdraw.

While there are many cases

of individual corruption, there is a deeper, systemic problem. Only

those who

are dedicated to bringing it down can resist the discreet charm of

capitalist

state power. Reformists, including those who out of habit and a

defective

memory call themselves socialists or communists, seek to pressure the

capitalist rulers. So what better way to gain influence than from the

inside?

This is their reasoning. Thus, while opposing “free trade” agreements

with the

U.S., Luis Macas, president of the CONAIE and former presidential

candidate of

the Pachakutik party, emphasizes that it’s not just a matter of voting

against

it, but of negotiating better agreements. From this viewpoint, its

logical that

he would end up voting for Correa for president. And the PCMLE, which

remained

in Gutierrez’s cabinet until it was forced to depart, doesn’t flatly

oppose

Correa’s repression in Dayuma, but instead offers counsel and a polite

request

that “the President of the Republic speedily resolve the current

situation” (En

Marcha, 15 December 2007).

We Trotskyists who fight

for the program of permanent revolution insist, today as in the past,

that the

only way to liberate the workers, peasants and indigenous peoples,

Afro-Ecuadorians and women, is by way of socialist revolution, not as a

distant

later “stage” but as the order of the day, resulting from the seizure

of power

by working class, supported by the poor peasants and Indians, raising

itself up

as a tribune of all the oppressed. To this end we seek to build a

genuinely

communist, revolutionary workers party, a Bolshevik Leninist-Trotskyist

vanguard, forged in struggle against social-democratic and Stalinist

reformism.

While for bourgeois and petty-bourgeois nationalists the forced

migration of

Ecuadorians is nothing but a tragedy, for the proletarian

internationalists it

represents an opportunity. The hundreds of thousands of Ecuadorian

workers now

residing in Spain and the United States can infuse the workers struggle

with an

internationalist spirit in their adopted countries and in the land of

their

birth.

In

the Old World of Europe and the New World of the Americas, from the

semi-colonies to the belly of the imperialist beast, we fight to

reforge the

Fourth International, world party of socialist revolution. ■

2 See “Ecuador: The ‘Rebellion of the Outlaws’ – A Marxist Analysis,” The Internationalist No. 21 (Summer 2005). A Spanish-language compilation of articles from the LFI on Ecuador can be found in Cuadernos de El Internacionalista, July 2003.

3 See our article, “Trotskyism vs. Constituent Assembly Mania,” October 2007.

4 See “Marxism and the Indian Question in Ecuador,” The Internationalist No. 17 (October-November 2003)

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com