November 2010

The Unions and the “Interpro” Assemblies

“reform” law. CFDT chief François Chérèque (in cap) and CGT leader Bernard Thibault (3rd from right).

(Photo: Gonzalo Fuentes/Reuters)

Thursday, November 4: The Lycée students are back. In the morning there were demonstrations at key airports. About 400 airport workers marched around Charles De Gaulle (Roissy) airport, bringing traffic to a virtual standstill. Workers blocked the entrance to the airport at Orly in the Paris region, as well as at Toulouse (450 demonstrators), Nantes and elsewhere. The aim was to delay early morning flights carrying business and government décideurs (decision-makers). By late morning the demonstrations had been dispersed. Meanwhile, supporters of the sanitation workers strike in Paris blockaded a second incinerator yesterday, at Saint-Ouen, where scab trucks were taking garbage, and have managed to shut it down. But the main event of the day was the rentrée (return) of the lycéens (secondary school students). This is their first day back after the two-week vacation for Toussaints (All Saints Day).

A demonstration has been called outside the University of Paris VII at Jussieu for 4 p.m. A couple hundred mostly lycéens are there at the starting time, eventually growing to about 400 when some university students from the Sorbonne showed up. The UNEF (National Federation of French Students) has a sound system and starts up their usual chants demanding the right to retire at age 60. A handful of anarchists have a banner, supporters of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) distribute their youth paper. After about an hour, as it becomes clear that the UNEF is just going to stay there chanting, about 250 protesters march off, including the NPA and most of the university students. As they leave, some of the marchers chant ironically, “UNEF, Medef, même combat,” saying that the UNEF (whose leaders are in or close to the Socialist Party) and the main employers’ association, the Medef, are on the same side. This is a play on the slogan “Étudiants, ouvriers, même combat” (Students and workers, same struggle, same fight) which has been a constant in demonstrations since the worker-student upsurge in May 1968.

Student

march passes the Sorbonne, November 4.

Student

march passes the Sorbonne, November 4.

(Internationalist photo)

The march winds its way through the Latin Quarter, up one side of the Sorbonne, then after some confusion heading down toward the tourist areas along the Left Bank of the Seine, tying up traffic along the way. So far no problem from the police. But after crossing over to the Right Bank and passing by some fancy stores, things change. As we head toward (Place de la) République, demonstrators notice columns of CRS riot police marching up behind us. Then as they turn around, they find the street in front blocked off by about a dozen or so well-built types in jeans and jackets who suddenly pull out the black metal clubs cops use to beat demonstrators. Behind them are busloads of CRS and gendarmes. A trap. Some marchers discretely peel off before the net is drawn tight. The police then proceed to detain the entire demonstration, several score at this point, loading them onto buses to take them to the station for processing.

In the evening we attended an Interprofessional General Assembly (AG) at the Bourse du Travail (Labor Exchange) in Montreuil, another working-class suburb of the “red belt” around Paris. The CGT union federation (in the past aligned with the Communist Party) has its headquarters in Montreuil. There were about 50 people at the AG, which was clearly a gathering of the local labor, left and student activists. It started out with reports from the different sectors: municipal workers, rail workers, education, etc. Some of the activists have started putting out a weekly collection of articles about the struggles, Jusqu’ici (Up to now), a “Temporary Bulletin of Dangerous Liaisons.” Initiatives like this have sprung up all around France.

There were some high school student activists at the Montreuil Interpro AG as well as teachers from the Lycée Jean Jaurès, where the student Geoffrey Tidjani was shot in the face by a cop using a FlashBall gun on October 14. A worker-student alliance at work: the lycéens asked for support for a planned blockade the next morning and several trade-unionists volunteer. Plans are made to meet in front of city hall on Saturday before heading off to the march in Paris. There was some tension when a local CGT leader tried to get everyone to march with the CGT départemental contingent and others objected.

Friday, November 5 was pretty quiet on the protest front. This is good since the weather was miserable, raining steadily all day.

Saturday, November 6: The day kicked off at midnight with a blockade of the newspaper Ouest-France underway in Rennes, in the Brittany region. From the beginning, Rennes has been one of the centers of resistance to the pension “reform” law of the Sarkozy government, among high school students, university students and workers. And Oeust-France, one of the biggest papers in the country, has been notorious for its slanted coverage of the struggle against the pension law. At 11 p.m. Friday, more than 100 demonstrators organized by the local Interprofessional General Assembly laid siege to the garage, blocking trucks from leaving the printing plant. After 2-1/2 hours the police dispersed the bloqueurs. (Bloqueurs, or “blockers,” have now replaced casseurs, or “smashers,” in the demonology of the government and bourgeois media.)

The blockade at the Saint-Ouen garbage incinerator is still holding strong, with up to 60 people in the evening and some camped out in tents to prevent the authorities from reopening it. The Socialist deputy mayor of Paris for cleanliness (in charge of garbage collection), François Dagnaud, is livid that the bloqueurs are not all sanitation workers. At the main incinerator in Ivry (see our report from November 2) he says there are “a group of rail workers, CGT members from Val-de-Marne and chemical workers, as well as garbage men”; at Saint-Ouen, his spies report “workers from the Citroën auto plant and school cafeteria workers from the city of Saint-Ouen.” Horrors! “Outside agitators” everywhere!! Dagnaud’s complaint gives an idea of the extent to which trade unionists from all over have been flocking to the blockades.

Demonstration

for the right to abortion and in defense of public hospitals, Paris,

November 6.

Demonstration

for the right to abortion and in defense of public hospitals, Paris,

November 6.

(Photo: Jean-Marc Bourquin/Photothèque

Rouge)

At noon, some 5,000 supporters of women’s right to abortion and public hospitals gathered at Place d’Italie before joining up with the march over the pension law at Bastille. Abortion is legal in France during the first trimester of pregnancy. (The League for the Fourth International is for free abortion on demand, at any stage.) There isn’t the same virulent anti-abortion movement in France as in the U.S., where “god squads” of “right-to-lifers” besiege the clinics, threatening and even murdering abortion providers. However, the French government has been closing abortion clinics, supposedly for budgetary reasons, even though the number of abortions is steady. The authorities have also been closing maternity clinics and hospitals, which have fallen from 1,200 in the 1980s to roughly 600 today. It is getting so bad that one speaker, a doctor, referred to the “pseudo-right to abortion.” Along the march route, some anti-abortion thugs tried to provoke a brawl.

Women have also played a prominent role in

organizing the protests against the government's law raising the

retirement age, fighting for full equality. In addition to receiving

lower wages than men (17 percent less, according to a recent study) and

often working part-time, both of which lower their pensions, if women

have interrupted their careers to have children, it can substantially

delay the age at which they are eligible for retirement at full

pension. Thus the average pension for women is €826, compared to €1,455

for men. This became so notorious that the right wing raised an

insulting proposal to let women who had three children retire at 65 at

full pension, but even that went nowhere. One of the demands of the

protests has been “1, 2, 3, with or without children, retirement at age

60 at full pension.”

Saturday afternoon, the eighth national day of action against the pension law: The story is: rain from beginning to end. Not only in Paris but in most of the 245 cities where there were mobilizations. A soaking, sometimes driving rain. A popular chant: “Le temps est pourri, le gouvernement aussi” (The weather is rotten, the government is too). At one point during the march we wonder about doing a remake of the Gene Kelly movie, calling it “Chanting in the Rain.” But just then demonstrators go past singing (of course).

Attendance is way down from the previous mobilization on October 29, but despite the downpour it is still sizeable: 1.2 million nationwide, according to the CGT. Ten days ago the unions reported 170,000 marched in Paris, this time 90,000, which may be generous, but in any case it’s far more than the ridiculous 28,000 claimed by the police. Yet the union bureaucracies managed to make it appear smaller by dividing the march into two different routes going from République to Nation, so that the CGT was in one column and the CFDT, F.O., FSU and other federations in a second. A perfect way to undercut the ties between workers in different unions that have flourished in this struggle. No wonder the CGT functionary was so hot to get everyone from Montreuil to march with his contingent! There was an operation going on here to get protesters back in the bureaucracies’ control.

“Public opinion” is still with the

protesters: a poll

by the Journal du Dimanche reported

that 70 percent support today’s mobilization. Once again, marchers

expressed

their determination to keep up the opposition to Sarkozy’s hated law. A

worker

from the Grandpuits oil refinery told L’Humanité

(8 November): “People tell you that there is no more solidarity in

France. I had

no idea how wrong that was. That is what is going to stay with me from

this

movement, not the fact that the law was passed.” A bus driver from

Rouen complained that

“Nicolas and his court should leave their palaces” and mingle with the

people.

The attacks on social programs are not over, next they are going after

social

security, he added: “It looks like we’re going to be marching a lot

until

2012,” when the next presidential elections are held. A number of

strikers

wondered how to keep the strikes and job actions going. One proposal is

that

rather than one sector going it alone in a proxy strike for everyone,

like the

refinery workers this time, instead all workers should contribute to a

strike

fund for those who walk out. Good idea, but what’s needed is to bring

out all

workers – nothing less will move this hard-line rightist government.

The real

problem is the leadership, which is deathly afraid of a general strike,

precisely because it poses the question of power – which class shall

rule. And

they are ultimately loyal to capitalism.

“Public opinion” is still with the

protesters: a poll

by the Journal du Dimanche reported

that 70 percent support today’s mobilization. Once again, marchers

expressed

their determination to keep up the opposition to Sarkozy’s hated law. A

worker

from the Grandpuits oil refinery told L’Humanité

(8 November): “People tell you that there is no more solidarity in

France. I had

no idea how wrong that was. That is what is going to stay with me from

this

movement, not the fact that the law was passed.” A bus driver from

Rouen complained that

“Nicolas and his court should leave their palaces” and mingle with the

people.

The attacks on social programs are not over, next they are going after

social

security, he added: “It looks like we’re going to be marching a lot

until

2012,” when the next presidential elections are held. A number of

strikers

wondered how to keep the strikes and job actions going. One proposal is

that

rather than one sector going it alone in a proxy strike for everyone,

like the

refinery workers this time, instead all workers should contribute to a

strike

fund for those who walk out. Good idea, but what’s needed is to bring

out all

workers – nothing less will move this hard-line rightist government.

The real

problem is the leadership, which is deathly afraid of a general strike,

precisely because it poses the question of power – which class shall

rule. And

they are ultimately loyal to capitalism.

The leaders of the Intersyndicale union coordinating committee were all lined up at the head of the Paris march, but the differences among them are becoming accentuated. Bernard Thibault vows that the CGT is going to “go to the end,” no matter what the other federations do. Same story from Annick Coupé of the Solidaires union federation (associated with the New Anti-Capitalist Party, NPA): “We’re not capitulating, we’re keeping on to the end.” Even David Assouline, the spokesman for the Socialist Party, says: “We’re keeping on to the end.” Olivier Besancenot repeats the NPA slogan, “We won’t let up.” So what does that mean, concretely? Zero. It’s a way of sounding militant without committing to anything. Jean-Claude Mailly once again calls for a one-day general strike, but didn’t bother to mobilize the Force Ouvrière ranks. Others bureaucrats say elliptically that the movement “has entered a new stage.”

The bottom line is that all of these left-talking labor lieutenants of capital are seeking to somehow bring to a conclusion a social movement which they have been trying to call off for weeks, without success. A new meeting of the labor federations, the Intersyndicale, is scheduled for Monday. At its conclusion, the union leaders announce … yet another Day of Action, on November 23. But this time the initiative will be passed to the local level, with meetings, rallies and “decentralized” demonstrations. That really will be a baroud d’honneur, a symbolic last stand, as the bourgeois press has been announcing for weeks.

Saturday evening, Interpro general assembly: After the demonstration, an Interprofessional general assembly for the Île de France region brought together several dozen waterlogged activists to evaluate the struggle. At the same time a first national coordinating committee (an “AG of the AGs”) was being held in Tours. The discussion focused on the role of the trade unions. Everyone recognized that the union leaders were banking on the mobilizations running out of steam, even the lousy weather was welcome for them. But what about the unions themselves? To deal with that question it’s necessary to make a brief foray into the history of the French labor movement.

At present and ever since the start of the anti-Soviet Cold War (1947-48), unions in France have been divided roughly along political lines. For decades, the CGT (General Federation of Labor) was essentially run by the Communist Party (PCF). Force Ouvrière (F.O.) from its inception was close to the Socialists. The CFDT (French Democratic Federation of Labor), which arose out of the Christian trade unions in the 1960s, was associated with another social-democratic current and then the Socialist Party (PS) after it was refounded under François Mitterrand in the ’70s. The SUD (Solidaires Unitaires Démocratiques) unions – which mostly date from the late 1980s and early ’90s, coming out of a conglomeration of non-aligned or autonomous unions – are aligned with the latter-day “far left,” notably (but not exclusively) the NPA. In many sectors, workers may choose between four or more unions, according to their political persuasion.

The alignments have shifted a bit over the years, so that today the leadership of Force Ouvrière is close to another “far left” current, the POI (Independent Workers Party), and the CGT leadership is sometimes at odds with the PCF (whose supporters have a strong presence in the union). Yet while divided according to political chapelles, or denomination, giving rise to petty organizational squabbles, today all of the union leaderships and the parties associated with them are thoroughly reformist – that is, they do not seek to overturn, but rather to work within the capitalist system. Over the last century, the domination of the leading union federations by reformist leaders and parties has clashed with the militancy of the French working class. This acute contradiction and the sellouts by the labor misleaders have produced a strong strain of syndicalism, whose adherents hold that the unions can make a revolution and who are opposed to parties, particularly a revolutionary party. This current today has an organized expression in the anarcosyndicalist CNT (National Federation of Labor), but as a prejudice it is fairly widespread.

The reformist stranglehold on the unions has also spawned minority tendencies which oppose trade unions as such. (Lenin polemicized against those who refused to work in trade unions in his booklet, Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder [1920]. Today, 90 years later, it’s more like a senile disorder.) There is a range of such groups, some to the right of the unions, others adopting an ultra-left stance. In the U.S., the World Socialist Web Site argues that unions are purely bourgeois institutions, and sometimes even sides with the bosses against them – for example, urging workers to vote against the United Auto Workers in representation elections. The WSWS leader is also the CEO of a non-union printing company. In Europe, on the other hand, similar arguments can be heard from some genuinely leftist militants repulsed by the sellouts of the CGT/PCF, CFDT/PS etc.1 So at the regional Interpro AG on November 6, a number of workers and others argued that the Interpros should oppose the unions as such, because of the way the latter sabotaged the struggle against the Sarkozy government’s pension law.

We intervened in this discussion speaking for the LFI, arguing that the labor bureaucracy is a petty-bourgeois, labor-aristocratic layer that acts as a transmission belt for the bourgeoisie, but at the same time they sit atop the unions, which are workers organizations. As a consequence, in order to maintain a minimum of credibility and control over the ranks, they are sometimes obliged to undertake, in their bureaucratic manner, some working-class struggles, if only to sell them out down the road. While they are parasites, they also have a certain interest in maintaining the organizations that they feed off of, even though ultimately they may cede to the pressure of the capitalists in destroying the unions.

In the current struggle in France, we noted, the strength of the mobilizations was due, in the first place, to the fact that the Intersyndicale leadership of the main trade-union federations called them and actually mobilized to bring out their ranks; and secondly, to the powerful impulse from the oil refineries strike in particular (as well as rail, port and sanitation workers). These same leaders have also sabotaged the struggle from the beginning, by not calling out all workers to strike against the government’s attacks, and now they are shutting down the struggle. The Interpro assemblies have played an important role in a number of places in setting up blockades that allowed workers to “strike by proxy.” But without the unions calling actions in the first place, they would not have been able to play that role.

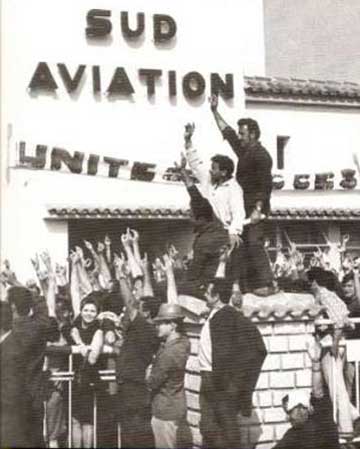

Union

militants led occupation of Sud Aviation factory in Nantes, setting off

a wave of plant occupations during May 1968.

Union

militants led occupation of Sud Aviation factory in Nantes, setting off

a wave of plant occupations during May 1968.

(Photo: libcom.org)

The issue of the dual character of the labor bureaucracy and the reformist, or as Lenin called them, bourgeois workers parties, came up again in a discussion about the call for a general strike, which almost everyone in the half dozen Interpro assemblies we attended agreed with. We intervened a second time, saying the question is how one brings about a general strike. It is necessary to raise that demand on the unions, though not just on the leadership (as some left groups do), who are never gong to agree to it. At the same time it is necessary to struggle for it among the ranks and among non-unionized workers. In big strikes it frequently happens that local coordinating committees are set up to overcome union divisions, like at the SNCF depot at Rouen-Sotteville in the 1986 rail strike. These could be turned into elected strike committees.

We pointed to the example of how the French general strike in 1968 came about, beginning with a one-day “general strike” on May 13 called by all the union federations which brought out up to a million demonstrators in Paris, the biggest mobilization since World War II. The initiative then passed to the ranks. On May 14, the unionized workers at Sud-Aviation in Nantes occupied the factory and locked the director in his office. On May 15, unionized workers occupied the Renault-Cléon plant near Rouen, the Bordeaux shipyards and another Sud-Aviation plant (in Cannes). On May 16, Renault plants at Flins and Boulogne-Billancourt next to Paris were occupied (see time-line, below). What was needed, we summed up, is to struggle both within the unions and outside for a class-struggle leadership to oust the bureaucracy, and for a revolutionary workers party to lead the struggle for socialist revolution.

Today, although it has been an open secret that the union leaders were trying to end the struggle against the pension “reform” law, there is actually little struggle against the labor bureaucracy. If workers think their leaders are sellouts, they join another union. Even the NPA and the SUD unions did not criticize the CGT and CFDT tops for pushing the oil refinery strikers back to work just when their walkout was having an effect. Instead, the ex-“far leftists” excused this betrayal, claiming the workers were tired.

As the regional Interpro meeting was concluding, one of the participants asked pointedly: “Why isn’t the far left here?” Their absence was indeed notable. The answer is that no less than the federations led by supporters of the PS and PCF, the unions and political organizations associated with what is now being called “the other left” are also committed to the capitalist framework, so they act through or seek to pressure the union bureaucracy. In the aftermath, though, they are working overtime to “recuperate” the Interpros. In the absence of a genuinely revolutionary vanguard they may succeed – until the next explosive wave of struggle. ■

|

How

the May 1968 General Strike Began

Excerpts from Reflections on the

Revolution in France, ed. Charles Posner (Penguin 1968).

|

1 Even coming from self-described “left communists,” this political line can lead to very reactionary positions. In the current French struggle, one such group, the International Communist Current, which claims that the unions have gone over to the “camp of the bourgeoisie,” put out a supplement with a front-page article, “Blocking the Refineries, A Double-Edged Weapon.” The article declares that “‘blocking the economy to put pressure on capital’ is a myth inherited from the 19th century,” and criticizes the refinery strike on the grounds that “workers every day are having trouble finding gas to get to work.” Even recognizing that “for now many proletarians support these blockades,” it warns against “paralyzing transportation” because it would hit workers first, and pose “an even greater risk, of making this struggle ‘unpopular’.” Disgusting anti-strike propaganda! Since the unions called these strikes, the ICC echoes the bosses’ press about how they inconvenience the workers. French workers gladly accepted the inconvenience because they knew that the refinery strikes had the potential of bringing the bosses to their knees. What a disgrace, pseudo-left “communists” who act as propagandists for the bourgeoisie!!

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com