No. 5, April-May 1998

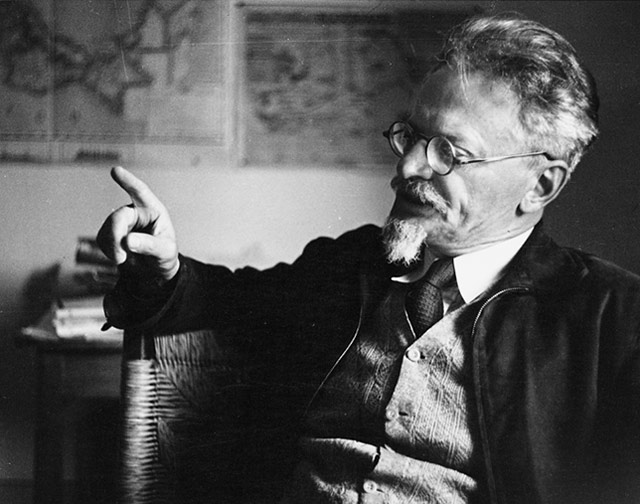

Leon Trotsky in Coyoacán, Mexico, 1939.

Photo © A.H. Buchman

The 1989-92 wave of counterrevolution that destroyed the Soviet Union and the East European bureaucratically deformed workers states has led to a sharp political degeneration in the International Communist League (ICL), which for more than three decades led the fight for authentic Trotskyism. This has been expressed in a growing tendency to abstention from the class struggle, most dramatically the ICL’s desertion from a key battle for the independence of the workers movement in Brazil in mid-1996. This tendency was also a key factor in the successive waves of expulsions of leading cadres and youth comrades who opposed the organization’s new centrist line as it was taking shape. As it flees from the class struggle and “cleanses” its ranks of troublesome elements, while trying to cover its tracks under a welter of lies, the ICL leadership also flees from the Marxist program. In the course of polemicizing against the Internationalist Group, the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista do Brasil and the Permanent Revolution Faction, the ICL leadership has revised a series of key Trotskyist positions:

“Trotsky’s assertion in the 1938 Transitional Program that ‘The world political situation as a whole is chiefly characterized by a historical crisis of leadership of the proletariat’ predates the present deep regression of proletarian consciousness. The reality of this post-Soviet period adds a new dimension to Trotsky’s observation.”

So in weasely phrases about “predating” the present and adding a “new dimension,” the ICL has declared out of date the reason for the existence of the Fourth International. It is no accident that virtually every revisionist current has objected to this same key concept. We have pointed to the growing abstentionism of the ICL leadership. This is not only a failure to intervene actively in various struggles. Here the ICL is trying to give a theoretical justification for an abstentionist program, claiming that the problem is no longer a crisis of leadership but of the proletariat itself.

That this is not just a flawed or skewed formulation but a whole policy is shown by the origin of this phrase in the new principles of the new ICL. In a 2 October 1996 letter, the historical leader of the ICL Jim Robertson polemicized against the founding statement of the Internationalist Group, quoting the sentence, “The central thesis of the 1938 Transitional Program of the FI fully retains its validity today,” and commenting: “To simply say ‘fully retains its validity today’ is insufficient.” He continued:

“Today, the crisis is not limited to the crisis of revolutionary leadership of the working class. The working classes across the world are qualitatively politically more disoriented and organizationally more dispersed. Today, to put it roughly, we have been forced back before 1914 and without the mixed blessing of an assured, complacent, mass Social Democracy.”

In other words, the crisis is now supposedly that of the working class itself, which is today allegedly too “disoriented” and “dispersed” to carry out its historic mission.

Over the past two years, there has been a mounting refrain in the ICL about a supposed “historical retrogression in the political consciousness of the workers movement and left internationally,” as the October 1997 call for the ICL’s third international conference states. In the recent fight in the ICL, the comrades of the Permanent Revolution Faction objected to this and to the rejection of Trotsky’s thesis that “The historical crisis of mankind is reduced to the crisis of the revolutionary leadership.” The PRF wrote that the ICL’s new line represents “a deeply idealist, and at the same time empiricist vision of history,” saying that if Pabloism was Cold War impressionism, this is a sort of “ ‘New World Order’ impressionism.”

Indeed, Spartacist members have more than once referred to a “new world reality” since the counterrevolution in the Soviet Union, seemingly unaware that this was Pablo’s catchword in justifying his own earlier rejection of the same key concept of the Transitional Program. Pablo said in a speech to the French section leadership in 1952:

“We will discuss with our comrades...who will leave aside the Transitional Programme which was written in an entirely different period. What has happened during and since the war is colossal. New things have appeared. Marxist thinking that tries to take refuge behind the phrases of the Transitional Programme is unacceptable to the Trotskyists.”

–quoted by S.T. Peng, “Pabloism Reviewed” (January 1955)

But the ICL does not stop there. The IG wrote in its founding statement: “The counterrevolutionary destruction of the Soviet Union was a major defeat for the world proletariat. Yet the defeatist conclusions the ICL leadership has drawn from this are an echo of the bourgeoisie’s ‘death of communism’ campaign.” Confirming this charge, Jim Robertson in his October 1996 letter charged the IG with “insensitivity” to a “qualitative change which had occurred and which is part of a larger change which has been trumpeted around by the ruling classes as the ‘death of communism’.” This accepts the validity of the bourgeoisie’s claim, only quibbling about the name they assign to it.

In contrast to this profoundly demoralized conclusion, the document of the ICL’s second international conference (1992) noted that the “fatuous ‘bourgeois-democratic’ triumphalism” had “largely dissipated” since 1989. Still, it wrote, “The ‘death of communism’ propaganda has had a deep impact on the left.” Now it must be added: including on the ICL.

It is striking how the ICL is now repeating, often word for word, the views of the Pabloist liquidators on a series of key questions. Thus, for example, Daniel Bensaïd, the principal theoretician of the United Secretariat (USec) today, writes in terms almost identical to those used by Jim Robertson of the ICL:

“The crisis of revolutionary leadership on the international scale can no longer be posed in the terms of the 1930s. It is not reduced to a crisis of the vanguard and the necessity to replace the bankrupt traditional leaderships by an intact relief team. What is on the order of the day is the social, trade-union and political reorganization of the workers movement and its allies on a planetary scale.”

–from the preface to François Moreau, Combats et débats de la IVe Internationale (1993)

Furthermore, the ICL’s 1997 Draft Declaration of Principles is “predated” by the 1992 Programmatic Manifesto of the United Secretariat, which states in almost identical terms:

“The crisis of humanity, in the last analysis, is the crisis of leadership and of the consciousness of the wage earners.... But the crisis of credibility of socialism which has prevailed for the last decade adds a new dimension to this crisis of leadership.... The skepticism of the masses concerning a global project of society that is different from ‘social’ capitalism tends to fragment movements of protest and revolt.”

This is no mere conjunctural analysis. The ICL and USec are here putting forward a virtually identical view of the world today. Their conclusions are different: the leaders of the United Secretariat are preparing to abandon any reference to Trotskyism, declaring that the idea of a world party of socialist revolution is out of date, because the crisis of humanity is no longer that of the revolutionary leadership but rather a crisis of the working class itself. They have become thoroughly social-democratized, and their program is at best that of the Second International’s old “minimum program.”

The leaders of the International Communist League say that because of the supposed qualitative retrogression in workers’ consciousness, “for the first time since the Paris Commune, the masses of workers in struggle do not identify their immediate felt needs with the ideals of socialism or the program of socialist revolution” (January 1996 memorandum of the ICL’s International Executive Committee). They seek to “build the party” in isolation from intervention in workers struggles. They now seldom raise transitional demands, but simply repeat the “maximum program” of the Second International, the one that was reserved for Sunday speechifying. Thus the ICL is on the road to becoming left-centrist “maximalist” social democrats.

The programmatic conclusions are different from the USec, but they are two sides of the same coin: in the first case through untrammeled opportunism, in the second by increasing abstentionism and purely abstract propagandism, both result in abandoning the struggle to forge a genuinely revolutionary leadership of the working class.

The thesis that the delay of the world revolution is due to the lack of revolutionary consciousness of the working class is an old theme. Trotsky polemicized against this view in his unfinished 1940 essay, “The Class, the Party and the Leadership.” His remarks were directed against a small French periodical, Que faire (What Is To Be Done), which blamed the crushing of the Spanish Revolution on the “immaturity of the working class.” As Trotsky pointed out, this piece of sophistry, unloading the responsibility of the leaders on the masses, is the “classical trick of all traitors, deserters, and their attorneys.”

This is also a common refrain among those seeking to justify the rejection of Trotskyism. Thus in the late 1940s, an article by Henry Judd on “The Relevance of Trotskyism” in Max Shachtman’s New International (August 1949) stated:

“Perhaps the outstanding difference between the past of Trotsky and our present is the absence of this mass of human beings in whom socialist consciousness to one or another degree existed. In no nation of the world today does there exist a body of workers possessing a socialist consciousness in the traditional sense of this word.”

The author’s conclusion: “It’s doubtful...that the concepts of classic Trotskyism can be of much assistance based as they are on the existence of a mass social consciousness forever expanding under the lash of experience and the teachings of the original party.”

More recently, in the 1980s the right-centrist Workers Power group (which came out of the International Socialism tendency of Tony Cliff, who held the Soviet Union to be “state capitalist”) declared that the Fourth International was not only organizationally destroyed, but that what was required was a “creative re-elaboration” of a new program for a new international in a new period. WP “theoretical” hot-shot Mark Hoskisson called for a “strategic retreat” in which, “In place of the Transitional Programme’s general denunciation of reformism a programme of action utilising the tactics of the united front was required” (“The Transitional Programme Fifty Years On,” Permanent Revolution No. 7, Spring 1988). The creatively re-elaborated WP program wrote off the program of the Fourth International as peculiar to the pre-World War II period:

“Trotsky’s Transitional Programme, written in these years, pronounced that the crisis of humanity was reduced to the crisis of leadership. However, today it would be wrong simply to repeat that all contemporary crises are ‘reduced to a crisis of leadership.’

“The proletariat worldwide does not yet face the stark alternative of either taking power or seeing the destruction of its past gains.”

–League for a Revolutionary Communist International, The Trotskyist Manifesto (1989)

The ICL replied then to this anti-Trotskyist diatribe by the barely reconstructed Cliffites:

“Try telling that brazen lie to American unionists who have seen a massive onslaught against the unions, whose real wages have fallen steadily for the last two decades; tell it to ghetto black youth, an entire generation that capitalism has thrown on the scrap heap with no hope of ever getting jobs; tell it to British, French and West German workers who have suffered almost a decade of double-digit unemployment; tell it to the working people of East Germany, fully half of whom (and even more among women) have been thrown out of work as a result of the counterrevolution of capitalist reunification; tell it to the immigrant workers, who are the target of racist terror and suffer the sharpest blows of capitalist austerity; tell it to the masses of East Europe, reduced to starvation wages and soup kitchens; tell it to the interpenetrated peoples of Yugoslavia being ripped apart in bloody nationalist war; tell it to the masses of the ‘Third World,’ including tens of millions of industrial workers producing for the imperialist markets, who are sinking ever deeper into immiseration! What profound confidence in capitalism Workers Power has.”

–Jan Norden, “Yugoslavia, East Europe and the Fourth International: The Evolution of Pabloist Liquidationism,” Appendix 2, Prometheus Research Series No. 4 (March 1993)

Yet today the ICL joins Workers Power in saying that it would be “insufficient” to say that the crisis of humanity is reduced to the crisis of revolutionary leadership; it joins the United Secretariat in saying that a “new dimension” must be added.

But even if it is admitted that latter-day Pabloists, Shachtmanites and Cliffites all latch onto the thesis that “classic Trotskyism” is not relevant because of lack of socialist consciousness in the working class, could it nevertheless be true that there has been a qualitative “retrogression” in socialist consciousness? USec leader Bensaïd writes that “at the time of the Moscow trials, of the Spanish Civil War, and on the eve of the world war, the formula [of the Transitional Program on the crisis of revolutionary leadership] had an incontestable currency,” but not now. The ICL says that “in no country today can we say, as Trotsky said about the workers of Spain in the 1930s, that the political level of the proletariat is above that of the Russian proletariat on the eve of the February Revolution” (Le Bolchévik, Spring 1998).

These parallel arguments distort the situation then and now. Trotsky wrote the Transitional Program as the Spanish Revolution was in the throes of defeat, and he emphasized that the Fourth International was born of “the greatest defeats of the proletariat in history.” Did those defeats have an impact on workers’ consciousness? Certainly. But Trotsky did not therefore throw up his hands and bemoan a “historical retrogression in the political consciousness of the workers movement and the left internationally.” Instead, he emphasized that, “The orientation of the masses is determined first by the objective conditions of decaying capitalism, and second, by the treacherous politics of the old workers’ organizations.”

Moreover, to pretend that the world proletariat as a whole had a similar level of consciousness to that of Spanish workers at the start of the Civil War, or that Trotsky’s thesis about the crisis of revolutionary leadership assumed such a level of consciousness, is sheer invention. What about American workers? The Transitional Program was written with the U.S. working class in mind. At that time, and throughout this century, American workers didn’t even have social-democratic consciousness but explicitly pro-capitalist ideas and supported the capitalist Democratic Party. What would a “historical retrogression” in their consciousness mean? Support for slavery, or for British colonial rule?

In fact, the political backwardness of the American workers was discussed at length prior to the founding of the Fourth International with leaders of the U.S. Socialist Workers Party, some of whom had argued the Transitional Program was too advanced. Trotsky noted in these discussions (19 and 31 May 1938) that “the political backwardness of the American working class is very great,” but stressed: “The program must express the objective tasks of the working class rather than the backwardness of the workers.” Again, he stated:

“It is a fact that the American working class has a petty-bourgeois spirit, lacks revolutionary solidarity, is used to a high standard of living.... Our tasks don’t depend on the mentality of the workers. The task is to develop the mentality of the workers. That is what the program should formulate and present before the advanced workers....

“The class consciousness of the proletariat is backward, but consciousness is not such a substance as the factories, the mines, the railroads; it is more mobile, and under the blows of the objective crisis, the millions of unemployed, it can change rapidly.”

And yet again: “I say here what I said about the whole program of transitional demands. The problem is not the mood of the masses but the objective situation.” Marxism or “scientific socialism” begins, “as every science, not from subjective wishes, tendencies, or moods but from objective facts, from the material situation of the different classes and their relationships.”

But what about in West Europe–can one discern such a decisive decline in socialist consciousness in the European working class? Today the consciousness of the vast majority of the European proletariat is reformist. It also had reformist consciousness 20 years ago when many labored under the illusion that Brezhnev’s USSR represented “real, existing socialism.” Certainly the destruction of the Soviet Union and the East European deformed workers states has “led many workers to question the viability of a planned economy,” as the declaration of the Permanent Revolution Faction states. But that does not mean that these workers have made their peace with capitalism.

The PRF also pointed out that the constant attacks by the bourgeoisie have pushed key sectors of the working class to undertake arduous battles against capital. In those struggles, the immediate obstacles are the reformist workers parties, whether openly social-democratic or ex-Stalinist, which are today in the government, often in the form of a “popular front.” In key centers of the class struggle, the crisis of proletarian leadership is as intense as ever, and the absence of a recognized revolutionary vanguard of the working class is if anything even more excruciating.

In Europe, the quintessential expression of this crisis in the recent period was the scene in Italy in late 1992 when workers exploded in fury at their reformist union and party leaders for having sold out the scala mobile (sliding scale of wages), a key gain of the 1969 labor battles. Among those pelted by worthless coins and bolts from the ranks were not just the ex-“Communist” social democrats of the PDS (Party of the Democratic Left) but also left-talking labor bureaucrats like the Metal Workers’ Bruno Trentin and the leader of Rifondazione Comunista, Fausto Bertinotti. Those workers urgently needed an independent revolutionary vanguard, yet virtually the entire Italian Trotskyoid “far left” is buried inside Rifondazione, even as loyal members of its leadership (sometimes critical, but not always from the left). As a result, working-class anger was siphoned off into the election of the Prodi popular-front government.

In France during November-December 1995, hundreds of thousands of workers struck for weeks and repeatedly mobilized massively in the streets. Yet the burgeoning movement was held in check and then called off by the PS/PCF bureaucrats at the point where it threatened to turn into a general strike. The labor fakers were able to pull this off with the vital aid of the ex-far left, now thoroughly integrated into union officialdom. With the popular front in office, the “big” pseudo-Trotskyist parties (LO, LCR, PT) are ostentatiously offering the Jospin government their services, hoping to get a piece of the class-collaborationist action (parliamentary seats, sinecures on government boards), while the smaller centrists try to pressure the “plural left” to the left.

In Latin America, this intensification of the crisis of revolutionary leadership is seen in explosions of working-class unrest in various parts of Argentina and elsewhere (Venezuela, Ecuador). They have been typically directed against bourgeois governments that were originally elected on a “populist” program, such as the Peronist Menem in Argentina, and who then implemented IMF starvation policies. Almost annually general strikes have been called in Bolivia against rightist regimes. Yet with virtually the entire “socialist” left on its knees as a result of the collapse of the USSR and East European deformed workers states, the revolts and strikes dissipate or are easily taken over and liquidated by bourgeois-nationalist demagogues.

Meanwhile, the Latin American left has thrown itself into building the Foro de São Paulo, a sort of continental popular front, whose stars are the Mexican bourgeois nationalist Cárdenas and Brazilian social-democratic Workers Party (PT) leader Luis Inácio Lula da Silva. From the ex-guerrilla bourgeois liberals of the Nicaraguan FSLN and Salvadoran FMLN to the Castro-Stalinist Cuban Communist Party to various pseudo-Trotskyists, they are all in the pop front stew. The last meeting of the Foro (August 1997) brought it all together with Cárdenas embracing Lula under the auspices of the Mandelite PT mayor of the Brazilian state capital of Porto Alegre. In the past, the ICL stood out for its denunciation of popular-frontism in Latin America, not only in Chile and Brazil but also in Argentina, Bolivia, Central America, the Dominican Republic and Mexico–where there are no mass workers parties.

In East Asia, the powerful general strike of South Korean workers in January 1997 was run into the ground by a supposedly “militant” union leadership beholden to the bourgeois liberal opposition led by Kim Dae Jung. A year later, Kim has been elected president with a “mandate” from the imperialist and national capitalists to enforce the brutal conditions of IMF loans. Sacrificed on the alter of a popular front of class collaboration with this capitalist “democrat,” whose prime minister earlier served as front man for the South Korean military regime, workers now face the prospect of more than a million layoffs. Here, too, the situation cries out for a revolutionary workers party, fighting for revolutionary reunification of Korea, for political revolution in the North Korean deformed workers state to oust the parasitic Stalinist bureaucracy, and for socialist revolution in the capitalist South, and the extension of the revolution to Japan and China. Such a party can only be forged on the program of authentic Trotskyism.

In Indonesia, bubbling discontent over the Asian economic crisis is being diverted by the Suharto dictatorship into chauvinist anti-Chinese riots, while militant unions are tied to the bourgeois-nationalist opposition leader Megawati (daughter of the former nationalist leader Sukarno). Here, too, popular frontism chains the workers and oppressed to the class enemy. As recently as a year and a half ago, the ICL denounced the danger of opposition popular fronts in Korea and Indonesia. Now, following the logic of its denial of a popular front in Mexico, it no longer mentions the popular front in its articles on these key Asian countries. It thus abandons a key programmatic component of Trotskyism.

Compared to the 1980s, one cannot talk of a qualitative, historical, deep decline in the will to struggle by the workers, or in desire for revolution or identification with socialism on the part of significant sectors. Yet beyond an evaluation of the period, the ICL leaders ultimately have an idealist conception of class consciousness. They see the role of the party as that of missionaries rather than as the advance guard of the proletariat, which develops the mentality of the workers through its sharp programmatic intervention in the class struggle. They have forgotten how quickly consciousness can change under the blows of economic and political crisis. They have the static view of those whose own consciousness is dominated by the accomplished fact. Like all revisionists, they underestimate the revolutionary capacity of the working class.

What is most notable in this “post-Soviet” period is the rapid collapse of self-proclaimed revolutionary organizations, the “far left” of yesteryear, including in particular many which falsely claimed to be Trotskyist. When the ICL talks of a qualitative retrogression in consciousness of “the left,” this has a degree of accuracy. But that should not require a retreat by the Trotskyists, quite the contrary. The policy of the pseudo-Trotskyists is tailism. Thus the USec laments in its 1992 “Programmatic Manifesto”:

“The masses themselves have not unleashed comprehensive struggles with an anti-capitalist dynamic over the last decade comparable to the 1960s and ’70s. There has not been a single victorious revolution since the Nicaraguan revolution of 1979. There hasn’t even been a single prolonged general strike in the imperialist countries or a single revolutionary explosion since the Portuguese revolution.”

So having no “radical” causes to tail after, the ex-“far left” becomes run-of-the-mill social democrats.

The ICL, registering that these former centrists have become reformists, that they no longer even pretend to be revolutionary, argues that this is the key fact for the ICL as well, and that we of League for the Fourth International are supposedly “insensitive” to this development. This argument demonstrates that the ICL defines itself as feeding off the petty-bourgeois, pseudo-radical left, seeing itself at the end of a continuum, the left of the “far left” which isn’t very left any more. Thus the ICL reflects the reformist “death of communism” syndrome at one remove. Yet the objective situation of the class struggle does not at all imply that authentic Trotskyism is more isolated.

The crisis of proletarian leadership is even more central to the crisis of humanity, and the collapse of Stalinism combined with the crisis of social democracy underscores the fact that only the program of Trotskyism can provide the revolutionary answer to this crisis. The evident bankruptcy of bureaucratic planning under Stalinist regimes, which foundered due to the impossibility of building socialism in one country, along with the wholesale dismantling of the social-democratic national “welfare state,” poses the need for international economic planning, governed by genuine soviet democracy, through world socialist revolution. What is urgently needed is a Trotskyist vanguard fighting to become the revolutionary leadership of the proletariat, a party that seeks to win workers to revolutionary consciousness through active intervention in the class struggle. Such a leadership would raise a program of transitional demands as the “bridge between present demands and the socialist program of the revolution.” It would fight popular-frontism around the globe. It would seek to mobilize the working class against counterrevolution and the tottering Stalinist bureaucracies that are treacherously preparing the way for capitalism in the remaining deformed workers states.

But today the whole pseudo-Trotskyist spectrum rejects such a perspective, instead seeking to join or pressure popular fronts and Labour/social-democratic regimes to the left, as assorted Pabloists and a host of reformist/centrist outfits do; or ostentatiously “pull[ing] our hands out of the boiling water” of the class struggle, as the International Communist League is doing in one country after another, from Brazil to Mexico and France. Abstentionism and revisionism go hand-in-hand as the ICL today heads down a centrist course. As the ICL abandons core elements of the Trotskyist program, the League for the Fourth International continues the struggle to break the chains that bind the exploited and oppressed to their class enemy and to build revolutionary workers parties as part of a reforged Fourth International. ■