June 2005

Bolivian

Workers Move Against

Threatened

“Constitutional Coup”

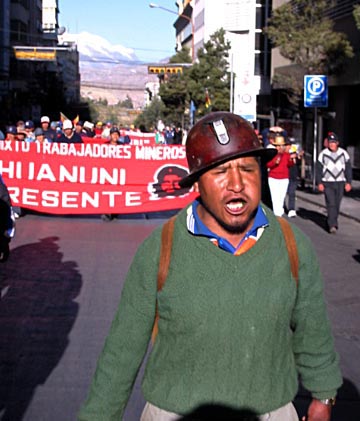

Miners in forefront

of battle against imperialist puppet governments in Bolivia. Facing

threat of

“constitutional coup,” thousands mobilized in the streets of La Paz

June 8 calling to drive out the

corrupt Congress. (Internationalist

photo)

For a Worker,

Peasant and Indian Government!

LA PAZ, JUNE 9 – Thousands of miners and

peasants have moved to surround the central zone in the city of Sucre

where the Bolivian Congress

was scheduled to meet this morning to decide on a new president. Huge

demonstrations demanding the nationalization of gas and oil resources

forced

unelected president Carlos Mesa to resign. Now parties from Bolivia's

military

dictatorships and the regime of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, which

massacred

protesters in October 2003, are vowing to install Hormando Vaca

Díez in the

presidency. This hard-line senator from Santa Cruz has vowed to “impose

order”

in the face of the mass mobilizations that have shut down the capital

and much

of the country for the past weeks. His attempt to take over has been

characterized as a “golpe

blanco” (a

“bloodless” or “constitutional”

coup

d’état). Meanwhile, the threat of an outright military takeover

is very real.

Radio

reports state that up to 6,000 miners from Potosí, Oruro, Uyuni

and other

areas have joined with peasants from Potosí and southern

Cochabamba to converge

on Sucre demanding that Vaca Díez abandon

his attempts to become president. Simultaneously, the Federation of

Miners

Cooperatives (Fencomin) marched through El Alto, the sprawling

impoverished

city on the heights above La Paz, saying if Vaca Díez does not

resign

there

will be “civil war.” Even sectors of the bourgeoisie are worried that

the

country could blow apart: the mayor of La Paz launched a hunger strike

against

the prospect of Vaca becoming president. The leader of the Movment

Toward

Socialism (MAS), Evo Morales, a party based on the coca-growing

peasants of the

Cochabamba region, is calling for the head of the supreme court to take

over

and call new elections. In return, Morales is offering to call off

protests,

knifing the miners and urban workers in the back.

Yesterday,

however, hundreds of members of the Federation of Mine Workers of

Bolivia

(FSTMB), historically the backbone of the labor movement, headed up a

huge

march through La Paz chanting “Death to the bourgeois parliament,” “Not

30 or

50 (percent tax on gas exports), but nationalization,” “With gas,

without gas, miners in La Paz” and other slogans. In a

communiqué, the

FSTMB criticized the demand for new elections as an attempt to

“evade the

nationalization of hydrocarbons” (gas, oil, etc.), stating that “the

existing

democratic system has degenerated and collapsed” and calling for a

“people's

revolutionary government” and a “Great National Popular Assembly.”

The

call for a “popular assembly” has been a central theme of what the

bourgeois

press sees as the “radical” wing

of the protests, sometimes counterposed to Morales’ call for a

“constituent assembly.” Frequently, the demand is linked to slogans for

“poder

popular” (people’s power) and a “gobierno popular” or “gobierno

del pueblo” (people’s government). The reference to a “people’s”

assembly

is a deliberate effort to distinguish such a body from a workers council

such as the soviets that were the organizing center of the

Russian

Revolutions of 1905 and 1917. The call for a “popular assembly” means a class-collaborationist

perspective, seeking an alliance with “progressive” elements of the

bourgeoisie, whatever its more leftist-posing proponents may claim. And

as with

Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular government in Chile, popular-frontist

class collaboration spells defeat for the exploited and oppressed.

Bolivian

tin miners from Huanuni march in La Paz on June 8.

Bolivian

tin miners from Huanuni march in La Paz on June 8.

(Internationalist

photo)

Yesterday

morning, a meeting in El Alto formally called into being an “Asamblea

Popular

Nacional Originaria” (National Popular and Native People’s Assembly).

The

meeting was called by the Bolivian Workers Federation (COB), the FSTMB

miners

union, the United Bolivian Peasant Union (CSUTCB), the national street

vendors

union, the Regional Workers Federation (COR) of El Alto and the

Federation of

Neighborhood Assemblies (Fejuve) of El Alto, with delegates from 60

organizations including the La Paz provincial transport union, La Paz

municipal

teachers union, Public University of El Alto and others. The first

resolution

of the “APNO” declared El Alto to be the “general headquarters of the

Bolivian

Revolution,” while other resolutions described it as an “instrument of

people’s

power,” called for delegates to be elected in assemblies and open

meetings (cabildos),

and for the formation of self-defense committees and supply committees

in every

sector.

Opportunist

leftists were quick to hail the new APNO as a “counterpower”

against the capitalist state. The right-wing press

went apoplectic, with a fire-and-brimstone editorial in La

Razón today

accusing the El Alto militants of “intimidation,” “terror,” seeking a

“totalitarian regime,” being like “Hitler’s Nazism, Mussolini’s

fascism,” and

the like. In fact, in October 2003 El

Alto was the target of a genuine

reign of

terror by a dictatorial regime, which the bourgeois media

wholeheartedly

supported. Yet the incipient Popular Assembly, as presently

constituted, is far

from being an organ of dual power. It was called into being in a

temporary

“vacuum” at the head of the government, while the capitalist state in

the form

of the army and police is still very much in place. For several leaders

of the

APNO, its proclamation was a fallback position, as in the case of COB

leader

Jaime Solares, who at key moments has

been angling for a “civil-military” regime with “patriotic” military

officers,

or Fejuve leader Abel Mamani, who is seeking a national dialogue under

the aegis

of the Catholic church.

The

current Popular Assembly is essentially a leadership cartel whose

future

evolution is uncertain. A genuine centralizing organ of dual power, a

soviet,

would have to grow out of dual power bodies throughout the country,

which do

not presently exist. Beyond the mass mobilizations, it is necessary to

form

workers councils of delegates, recallable at any time, as

well as peasants councils and councils of rank and file soldiers. They

must institute workers control

of vital factories, mines, transportation and communications

facilities; act as decision-making and executive bodies under

proletarian

leadership rather

than talk-shops for rhetorical hot air; organize self-defense

groups (the

core of worker and peasant militias) under the authority of the mass

organizations of the working people; and undertake the

distribution of

food and vital supplies to the population.

The

battle with the bourgeoisie will not be won simply by passively digging

in for

an endless strike – it is necessary to undertake positive steps

to

establish

workers power. Today, for example, with supplies of gas for cooking

dwindling

to zero in the capital, the impact of the El Alto strike and blockade

can be intensified

by carrying out distribution of gas to poor

neighborhoods, clinics, etc., under strict control by commissions of

the

Senkata YPFB plant workers, miners and slum dwellers. Such actions will

dramatically underscore the capacity of the workers to rule, in

contrast to the

corrupt bourgeois authorities. When this begins to happen, the

way will

be open to ending the present stand-off and advancing to workers

revolution.

The

calls for a Popular Assembly hark back to the body of

that

name which briefly existed in mid-1971 and has since become

mythologized by

various opportunist currents. The “Popular Assembly” of 1971,

headed

by left-nationalist mine union leader Juan Lechín, in

reality (despite sometime leftist declarations) supported the military-populist

government of General Juan José Torres, and

left the workers politically and physically disarmed in the face of the

long-awaited coup of rightist general Hugo Banzer. Its leaders went on

to form

a “Revolutionary Anti-Imperialist Front” with (by then deposed) General

Torres

and other bourgeois and reformist sectors. In fact, the current calls

for a

popular assembly in Bolivia are formulated so as to leave the door open

to just

the kind of class-collaborationist “alliances” that led to bloody

defeats for

the Bolivian workers, peasants and Indian peoples in the past.

Far

from calling to repeat the debacle of the Popular Assembly, a

Trotskyist party

in Bolivia would fight now for the formation of

workers, peasants and

soldiers councils, like those the Russian Bolsheviks led to

power in October

1917, which could be the basis for a worker, peasant and

Indian

government. Genuine soviets would be based on proletarian

internationalism,

rather than bourgeois and petty-bourgeois nationalism, extending the

hand of

solidarity to the Chilean, Peruvian and Argentine working people and to the

workers in

the

imperialist centers as well. This is the only way to defend the working

people

and oppressed from the threats that grow more dangerous with each

passing hour. n

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com