August 1999

Key Fight Against Capitalist Offensive

Mexico

The Battle for UNAM

Student Strike Under Siege

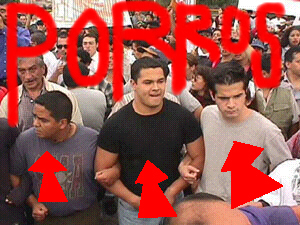

Duilio Rodríguez/La Jornada

University

workers union STUNAM confronts scabs, August

23.

Break with the Cárdenas Popular Front

--

Forge a

Revolutionary Workers Party!

Part 1 of 2

The following article is based on a supplement to El Internacionalista, published on August 3. It has been divided into two parts to make it easier to download. For Part 2 go to The Battle for UNAM, Part II.

AUGUST 24—The explosive student strike of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), now in its fifth month, is a political struggle of the first order. It is already the largest and longest student walkout in Mexico’s history. The thousands of students who are occupying 36 campuses and other university facilities have been the target of threats by President Ernesto Zedillo, insults by the high clergy and demagogic electioneering by candidates in next year’s national elections. Now right-wing scabherders are trying to set the stage for a police or military assault by attacking the strike with incendiary devices and trying to break into the huge Ciudad Universitaria campus in southern Mexico City. Vigilance and a militant response by strike defenders have repulsed these provocations.

Fighting for free public higher education, the strikers have repeatedly gone into the streets in the tens of thousands, alongside thousands of militant workers. In an important development, worker-student defense brigades were formed with the participation of hundreds of electrical workers and university workers. The strike is opposed by all the capitalist parties, from the governing PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) and the rightist PAN (National Action Party) to the bourgeois-nationalist PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution) led by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas. Although the limited demands of the strike are strictly democratic, at bottom it is part of a class struggle. To win this battle requires breaking politically with all wings of the bourgeoisie and extending the strike to key sectors of the workers movement.

When UNAM rector Francisco Barnés de Castro had his pliant University Council adopt a new General Schedule of Payments in mid-March, he never expected to unleash such tenacious opposition, nor that a strike by National University students would win support from important unions. It was a major miscalculation, one that Barnés now says he "repents" having taken. From the outset, there was massive opposition to his imposition of student "fees" amounting to 1,360 pesos (US$150) a year, the equivalent of a month’s salary for an industrial worker in Mexico. The UNAM chief justified the measure arguing that he was "raising the academic level" of the institution and attracting students from "the best private schools." In the face of his refusal to hold a university-wide discussion on this de facto introduction of tuition – which many professors called the beginning of the privatization of the National University – students called a walkout on March 12 which shut down the entire UNAM system with its 270,000 students.

When students threatened to attend the meeting to oppose the vote by the University Council, the administration began putting plywood in doors and welding them shut. When hundreds surrounded the Rectorate Tower in a plantón (sit-in), Barnés had the Council meeting held in a secret off-campus location, sending cars to pick up his flunkeys. On March 15, after scouring the city, students discovered that the meeting was being held behind barbed wire in the National Institute of Cardiology. Several thousand rushed to the scene where they were met by squads of porros (paid thugs) and several hundred Auxilio UNAM campus cops. More than a third of the Council members, including most of its student members and all who opposed the fees, were excluded from the meeting. Three days later, tens of thousands of students marched to Mexico City’s Constitution Plaza, the Zócalo, together with thousands of militant electrical workers protesting Zedillo’s plan to privatize electrical energy and with supporters of the Indian rebellion led by the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in the southern state of Chiapas.

In mid-April, after several mass student assemblies and another walkout at the 36 UNAM facilities in Mexico City, a Strike General Council (CGH) was formed. A vote was held in which well over 90 percent of the 110,000 who cast ballots opposed the introduction of fees and demanded a public "dialogue" with the rector. When Barnés still refused, the CGH called an unlimited strike starting at midnight, April 20. That night thousands of students occupied Ciudad Universitaria (CU) as well as the numerous junior college level Colleges of Science and Humanities (CCH) and UNAM-linked preparatory schools around the capital. At the Law School, some 1,200 strikers had to force out the director, Máximo Carvajal and a hundred of his thugs. Barricades were erected at CU entrances. In each department and school commissions were set up to take care of security, maintenance, cooking and other essentials.

Comité de

Huelga/Facultad de Filosofía y Letras

Scab-herding

thugs (porros) during August 23 provocation.

Over four months later, in the face of an endless barrage of threats, vituperation and constant provocations from the university administration, the bourgeois press and the government, and now escalating porro attacks, the red-and-black flag (the traditional symbol of workers strikes in Mexico) still adorns UNAM facilities. From the beginning, hundreds of students stayed through the night, later assisted by workers defense brigades, to guard against attack. CGH meetings are attended by up to 1,000 students or more; on those days, an average of 3,000 meals are prepared. Early on, students took over campus police offices and forced Auxilio UNAM cops off campus. Patrol cars were painted over with slogans denouncing repression. When it was discovered that electronic surveillance was being coordinated from a building near campus, several hundred students surrounded the building, forced the cops out and carted off boxes of videotapes and files on students. Excerpts from the detailed reports on demonstrations and meetings by the administration’s spies (orejas) were released to the press along with a bitácora negra (Black Book) by the Strike Committee documenting campus repression.

Organizationally, maintaining the strike and occupation of 36 different installations for more than 120 days has been an enormous undertaking. The students have braved police attacks on several occasions. On August 4, the government of the Federal District (Mexico City) headed by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas dispatched squads of granaderos (riot cops) who brutally beat students and parents picketing a scab registration operation, arresting 107. This caused a wave of outrage among the students, where Cárdenas’ bourgeois-nationalist PRD has traditionally had strong support. Despite the repression, strikers continued to send out brigades in many cases shut down the UNAM administration’s cynical ploy of registering students (and collecting "voluntary" fees from them) for non-existent classes at the struck university. Several student leaders have been kidnapped, beaten and slashed by goons. The strike has also had a tragic toll as a student was crushed by a bus after a demonstration at the Zócalo.

Class-Struggle Leadership Key to Victory

The battle for UNAM has been largely ignored by the bourgeois media outside of Mexico. One of the few items in the U.S. press, an article in the Houston Chronicle (25 July), condescendingly described the student strikers:

"They flaunt hair colors that range from fluorescent marine-green to a bold strip of spray-paint red. Yet they see themselves in the tradition of Cuba’s Che Guevara or Mexico’s Subcomandante Marcos.The university administration also clearly thought that UNAM students were an apolitical Generation X, and figured it could push through its plan to knife free public higher education by decreeing that the student "fees" would only apply to incoming student, not to those presently enrolled. This attempted bribe backfired, underscoring that the strikers were acting not for themselves but for those who would come after them.

"If this were a Hollywood script, it might be tagged ‘Emili[an]o Zapata meets Generation X."

Now the New York Times (13 August) complains that "the [UNAM] administration looks increasingly helpless" and that "neither the rector, Francisco Barnés de Castro, nor government officials want to storm the campus." The authorities are "constrained," the Times writes, by "the horrendous memories of 1968 when, shortly before the Mexico City Olympic Games, Mexican security forces mowed down waves of protesting students with gunfire" in the infamous Tlatelolco Massacre. But the Mexican regime hardly lacks bloodthirstiness: the massacres of Indian rebels in Acteal, Chiapas and peasant protesters in Aguas Blancas, Guerrero prove that. And any hesitations about the unpredictable consequences of an assault have not stopped the PRI-government from sending in its porros, with the police and army not far behind.

UNAM strikers have shown great determination and organizational capacity, and won broad support among working and poor people. Official repression, attacks by paid thugs, a campaign of demonizing the students in the media, ultimatums, unpostponable deadlines which are then postponed: nothing has gone the way the authorities hoped. Nevertheless, the strike has reached a dead end with the current strategy and strike leadership. It is no secret that participation in guard shifts has fallen off, although hundreds and even thousands of students are still at their posts together with the worker defense guards. Neither the openly pro-PRD "moderates" nor the reputed "ultras" in the CGH have a policy to win in the face of an obstinate adversary. It is possible to overcome the wear and tear that is the result of waging an intense struggle for such a long time, but what it will take is adopting a class-struggle policy capable of defeating the enemy through working-class mobilization, by striking a hard blow and not just digging in.

Above all, there is an urgent need for revolutionary leadership to win this strike. Up to now, it has been conducted under the watchword of seeking "dialogue" in order to "democratize" the unviersity. The Trotskyists of the Grupo Internacionalista have insisted from the outset that "dialogue" with the university bureaucracy, the instrument of the bourgeoisie, is a trap. This fight will not be won by inertia, nor by competing to see who is the more committed to dialogue. The main tendencies within the CGH talk of a university "in the service of the people," and of a struggle against "neo-liberalism." This populist language is typical of all nationalist bourgeois parties, such as the PRI historically and the PRD at present, and implicitly accepts the capitalist framework. Moreover, today all the presidential primary candidates of the PRI (Horacio Labastida, Roberto Madrazo, Manuel Bartlett and Humberto Roque) denounce "neoliberalism." The CGH is fighting on the same political terrain as the enemy, and that is no way to win.

Although in formal terms the fight for free public higher education doesn’t go beyond the bounds of bourgeois democracy, in fact it is fighting against a capitalist offensive. In this epoch of imperialist decay, above all following the capitalist counterrevolution in the Soviet Union and East Europe, the international organs of imperialism such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the OECD have ordered drastic budget cuts for public university education. In the midst of a frantic race to drive up the profit rate, none of the bourgeois parties or political currents takes a stand in defense of free public education. Thus the fact that the strike has become bogged down has a political explanation: the political subordination of all the tendencies active in the strike to an alliance, open or disguised, with a sector of the bourgeoisie.

As a member of the Grupo Internacionalista remarked at the strike assembly of the School of Sciences on July 13, today "the only way to defend the strike is at the same time the only way to win it; by extending it to the workers movement." The only way out other than capitulation consists in integrating the UNAM strike into a broader class offensive of the proletariat. The working class is the only social force capable of defeating the capitalist onslaught. Our June 23 leaflet was titled, "UNAM Strike at the Crossroads: Mobilize the Working Class to Win!" And this is not an impossible dream. The Grupo Internacionalista has fought tirelessly since before the beginning of the strike for a joint strike by the UNAM, the Electrical Workers Union (SME) and the dissident teachers of the CNTE (National Coordinating Committee of Education Workers). In our leaflets, in motions put forward at strike assemblies and in going to the most relevant unions, we have underlined the need for a worker-student defense of the strike. The presence of workers brigades from the powerful SME, the National University Workers Union (STUNAM), the Metropolitan University workers union (SITUAM) and other labor organizations defending the UNAM is the product of these efforts by the GI and above all of the understanding by broad layers of workers that the interests of all working people are at stake in the strike.

There is an immediate need for a vigorous defense of the strike. It is urgent to expand and extend the worker-student defense brigades to all UNAM facilities. We insist on the expulsion of all cops and porros of any sort from the UNAM, and urge STUNAM to throw the uniformed thugs (and plainclothes spies) of Auxilio UNAM out of their ranks. At the same time, it is necessary to fight for a joint strike together with important sectors of the labor movement (SME, CNTE, STUNAM, SITUAM and others) and to call for active support of workers and students on an international scale. Above all, it is necessary to forge a new class-struggle leadership for the strike to become part of a broad proletarian offensive against the onslaught of capital.

I. No to the Bourgeois "Democratic" Fraud –Week after week, the bourgeois media have waged a rabid campaign against the strike, presenting the students as stubborn elements who are unwilling to peacefully resolve the conflict, therefore supposedly leaving the authorities no alternative but to take back the installations by force. Reforma (21 June) printed excerpts from leaked reports from the federal ministries of the interior (Gobernación), defense, education and various spy agencies under the headline, "National Security Threatened by UNAM." The head of the UNAM School of Social Work – who is the sister of the deputy sectretary of the interior and long-time director of the Cesin intelligence agency – declares that "the UNAM case is a problem of national security and the government should intervene." In fact, the government is preparing a wave of arrests of leaders of the strike movement.

For a Class-Struggle Fight!

The university administration has acted throughout with authoritarian disdain for the strikers. On July 12, when representatives of the rector’s Contact Commission sat down in the Palacio de Minería to discuss arrangements for "dialogue" with the strikers, they denounced the strikers in unison as "subversives." Administration spokesman Rafael Pérez Pascual announced that they would not discuss any of the strikers’ demands. Another member of the rector’s Commission, Angel Díaz Barriga, vituperated against the students’ "dangerous popular democratic project," saying that "the institutions of higher education are neither democratic nor popular" (La Jornada, 13 July).

This openly anti-democratic rhetoric of the administration’s hired flunkeys recalls that of right-wing Catholic intellectuals in Spain in the 1930s such as Miguel de Unamuno and José Ortega y Gasset, who both greeted Franco’s military revolt against the republic in 1936. Two retired law professors of the UNAM Law School, Ignacio Burguoa and Raúl Carrancá y Rivas, have filed criminal charges demanding eleven years imprisonment of members of the Strike Council. They are joined in their hysteria against the student strike by the high clergy, which would be quite comfortable in a Francoist regime. The cardinal primate of Mexico, the bishop of Cuernavaca and the head of the education commission of the Mexican Conference of Bishops say that the strike is following orders from Subcommandante Marcos of the EZLN.

Now the president of Coparmex (the Employers Federation of Mexico) is insisting on "closing" UNAM "for a period of two, three, four or however many years are necessary," as the only way to solve the conflict. He also says that students must "be prepared to join the labor market in a competitive economy and a globalized world, and the UNAM is not giving them that." In the past, the National University provided cadres for the party-government of the PRI regime, and for the large number of state-owned companies and institutions. It continues to fill this function for Cárdenas’ PRD – just look at the number of UNAM ex-student leaders in the Federal District government. But since the rise of the "technocrats" led by former president Carlos Salinas and his disciple and successor Zedillo, graduates U.S. Ivy League universities, the National University no longer fulfills the same function for the ruling class. What Mexican capital and its government wants these days is above all that the university should educate management and professional personnel for private companies. If it were necessary to close the university in order to assert their control over it, they would do so.

Such calls are not isolated voices of fascistic elements but the expressions of the mindset of much of the bourgeoisie which is "tired of arguments which have been used up by history," as Excélsior (7 July) put it. Until recently, ruling class "hardliners" have limited themselves to "pots and pans demonstrations" of the "Women in White," calling on drivers on the Periférico (beltline highway) around Mexico City to turn on their lights to demand an end to the UNAM strike. Now they are unleashing their porros. In the final analysis, it comes down to the capitalist state with its armed forces. Jurist Burgoa, who supplied the pretext for a government crackdown, pretends he is only calling for the intervention of the "judicial force of law" and not the "public force" of cops and troops. But the latter are the indispensable armed fist of capital, and the core of its state.

II. "Moderates" and "Ultras" in the Cárdenas Popular FrontKey to understanding why the strike has bogged down is the role of the Cárdenas popular front. The PRI regime and the UNAM administration insist that the PRD is "behind the strike." They hold Cárdenas’ party responsible for all protests against the fee hike and the rest of the elitist "reforms" promulgated by the rector Barnés. The reality is rather different: it is well-known that the PRD leaders have repeatedly tried to stop the strike. For that very reason, particularly following the August 4 cop attack, there have been calls in strike committee meetings for the expulsion of the PRD and the student groups linked to it. However, even after the openly pro-Cárdenas "moderates" were discredited, the reputed "ultras" have also undercut the strike, looking for arguments to lift the occupation or to take flight at the first threat of action by the repressive forces. This is because these leftist currents are also part of the Cárdenas popular front. Even as they criticize the PRD, they recognize and respect the limits of what is tolerable for the bourgeois "opposition" to the PRI. In order to win this battle it is utterly necessary for the workers and student strikers to break with the Cárdenas popular front.

When after a month and a half of the strike the University Council, as always following the baton of its ex oficio leader Barnés, declared the new student fees to be "voluntary," pro-Cárdenas student Council members of the Democratic Coalition (CD), the University Student Council (CEU) and the University Student Network voted in favor of the modified Barnés plan. It was obvious to all that the Rectorate was counting on changing the voluntary" fees from "voluntary" to "required" as soon as things calmed down. At the same time, the University Council decreed heavy new fees for using laboratories and other university services. It was clear that nothing had been won, and student strikers were not about to accept the capitulation that the PRD prepared for them. Furious, Barnés leaked to the press that he had negotiated the changes directly with Cárdenas, and that the latter had met behind closed doors with PRD student leaders.

While student PRDers with their multiple organizations, now banded together in the Independent University Council (CIU), are trying to deliver the strike on a platter to the UNAM authorities, the Federal District and national government, the supposed leftist "ultras" have been stumbling over each other looking for the nearest exit in case of a serious clash. The most notorious case is that the the Partido Obrero Socialista (POS), labeled by Proceso (25 July) "the least radical part of the radicals of the University Left Bloc (BUI)." In a shameful leaflet dated July 3, the POS’ youth group declared: "After more than 70 days, the movement has become worn out, weary and weakened. It is a fact that we no longer have the presence of contingents of electrical workers in our mobilizations…." However, this "fact" was not a fact.

In its newspaper, El Socialista (July 1999) the POS speaks of "weariness" after such a long strike, and of "the perception of our strike by the population coming off the intense campaign of pressure by the government." While its previous issue headlined, "Long live the STRIKE!" the POS now pretends that the "voluntarization" of the student fees approved by the University Council "constitutes a heavy setback for Barnés and the Zedillo government." They insist that "The assemblies will have to be very objective in their analyses in order to determine the right moment to call off the strike and gains resulting from it, even if it’s felt that not all of the points of the list of demands have been met."

This is an unvarnished call for capitulation in the face of the onslaught by the government and above all by the Cárdenas popular front. The POS even joined the bourgeois brouhaha against "the ultras," publishing an entire page outrageously quoting Lenin and Trotsky against ultraleftism, while attempting to equate them with gems from their late maestro, Nahuel Moreno, in the social-democratic phase of his chameleon-like political career. Like all social traitors, the POS presents as "gains" what are really nothing but crumbs swept from the table of Barnés (with the approval of Zedillo and Cárdenas). Moreover, this disgusting defeatism came just as the first defense brigades were formed by STUNAM university workers and then SME electrical workers, and the day after SITUAM shut down the campuses of the second largest university in the Mexican capital in solidarity with the UNAM strike!

So where does the Morenoites’ zeal

to put an end to the largest and longest Mexican student

struggle in decades come from? They are not capitulating

to the current mood of the strikers, nor of the workers

who have come to support them. On the contrary, their

program directly reflects the pressure of the

bourgeoisie: the quote from the POS almost admits as

much. POS leader Cuauhtémoc Ruiz expressed illusions in

the PRD in an interview with Proceso (27 June), arguing

that "the Cárdenas government has to understand that it

must be more flexible in the way it applies the law."

When they came to realize that the head of the Federal

District government was ready to send the granaderos

against student strikers, as it had earlier done against

CNTE teachers, the POS leaders decided that the

moment had come to "determine the

right moment to call off the strike," i.e., to abandon

it.

These illusions of the POS in Cárdenas are not limited to tactical questions. In the Proceso article quoted above, after admitting that the PRD is a bourgeois party, Ruiz states: "At most it wants to make a democratic reform, not a revolution, which it should have done in 1988." "In 1988," the POS leader continued, "cardenismo sucked up all the currents of the left." Indeed. When Cárdenas visited the UNAM in May 1988 during his presidential campaign, the POS (then called the PTZ) published an open letter calling on him to "come out for unity in action" to "democratize" the university and "defend the vote." This attempt to sidle up to the former PRI politician (Cárdenas had been governor of the state of Michoacán) was part of Nahuel Moreno’s program for a "democratic revolution," in reality a reformist program of bourgeois populism.

Another component of the University Left Bloc, which has since split, is the En Lucha current, based in the School of Sciences. En Lucha and the Propaganda Commission of Sciences which it controls have published a series of leaflets and wall newspapers justifying the strike. En Lucha gave a certain workerist flavor to its propaganda, for example writing "SME, UNAM On to the General Strike!" (Antiojos, 16 March). But when spelled out in the text, what this came down to is that the SME should "declare its intention to strike" against the privatization of the electrical industry – a legal procedure asking permission to strike from the state Conciliation and Arbitration Board, which would never give it. For a number of weeks, En Lucha spokesmen opposed "dialogue" with the university administration, or rather demanded certain conditions before holding it. But at the decisive moment, En Lucha voted in favor of the phony dialogue with Barnés’ minions, leading the strikers into the trap and helping prepare the current dead-end of the strike.

A Discussion Document No. 9 (30

June) of the Sciences Propaganda Commission headlined a

call for "Firmness!" in the face of the

intimidation by the government and media. But in the

middle of the document they begin talking about "our

strike in exile," even as the occupation of university

facilities continued. This "strike in exile" is no doubt

conceived of as the "long march" by the ex-Maoists of En

Lucha, and the conception is hardly abstract. On the

night of July 7, when there were reports of troop

movements by the army, the watchword put out by the CGH

Security Commission was to evacuate the campus in the

event of an attack.

But the evacuation didn’t take

place, in large part because that night the first

workers defense brigades appeared, infuriating the

authorities. While the so-called "ultras" of the CGH

were getting ready to decamp into "exile," the Grupo

Internacionalista presented motions in strike committees

and spoke in union assemblies of the STUNAM and SITUAM

seeking to form workers defense guards, which in fact

were formed.

En Lucha sees an essentially student strike, dressed up with a little "popular" solidarity, which would be incapable of resisting the repressive forces. When they would occasionally send out brigades to factories or poor neighborhoods, it was mainly to collect money in cans and to receive passive shows of sympathy, not in order to win the workers to a common struggle. En Lucha tails after the union bureaucracies to give itself a little "labor" cover, and never fights to mobilize the ranks n a class-struggle program. At bottom, the panic which reigned among these alleged "ultras" in the face of the government’s threats was due to the fact that they, like the POS, look to Cárdenas.

In Document No. 9, En Lucha supporters write:

"Now the riot police are under the orders of Cárdenas, and he knows well that there would be a tremendous political price to pay for himself and his party if he dirtied his hands simply by occupying the University and repressing the student movement. This leads one to think that this possibility would be very difficult…very broad sectors of the worker, student, teacher and popular movement would never forgive him."Thus En Lucha bases itself on and feeds the illusions of sectors of the masses in Cárdenas & Co. But when it realized that the possibility of clearing out Ciudad Universitaria by the capital police wouldn’t be that "difficult" for Cárdenas, En Lucha made an abrupt about-turn and began to prepare to jettison the strike in favor of the chimera of a "strike in exile."

Strike

supporters fill Mexico City's Zócalo, May 1999.

Among the hardcore sectors of what the bourgeois press calls the "ultras"is the School of Political Science. In a leaflet they distributed together with strikers from the ENEP Acatlán (a UNAM-affiliated professional school) and others outside the Palacio de Minería, they criticized the 120 delegates of the student commission meeting there with the rector’s Contact Commission for usurping the functions of the CGH. But, significantly, the leaflet did not reject this phony "dialogue." It said: "Does it seem to you that sitting down with the authorities is an advance. No doubt it is." On the contrary, this didn’t represent an advance but rather accepting the terrain of battle of the bourgeoisie. The struggle for free public education will not be won in polite "dialogue" with the the deaf administration. It is necessary to wage it on the battlefield of the class struggle of the working people against the capitalist onslaught.

In calling for more combative tactics, the Political Science militants state that what is needed for a serious strike are "hardhitting actions, which force the authorities to give in faced with our organizational capacity." An example is "cutting off vehicular access to the Federal District for several hours" (leaflet by Political Sciences strike committee, May 1999). It is pure illusion to think that this would show the strength of a university strike against the bourgeois state. And as justified as it is to try to stymie the government, the immediate target of such actions would be automobile drivers. Above all, the political perspective behind such tactics is the same popular frontism of the supporters of "dialogue." In an interview with El Universal (24 June), Alejandro Echevarria, labeled by the bourgeois press the "megaultra" of Political Sciences, recognizes that taking over highways would only by "a political pressure action." To make matters perfectly clear, he stresses that "we are not against Cárdenas." Well, we are.

Once again, this is a reformist populist viewpoint. In the Political Sciences leaflets there are constant references to "the people," without class distinction: they speak of "winning greater popular support," of creating "spaces of people’s power," that "the only way to avoid repression is with the people," etc. This language is common to all tendencies in the reformist and nationalist left. The inveterate Stalinists of the Communist Party of Mexico (M-L), for example, call for a struggle "Against the Anti-People Policies of the Regime" (Vanguardia Proletaria, March 1999) and for "a democratic, scientific and popular university" (Joven Guardia, 9 July). En Lucha calls for "an education in the service of the people," and in its 1998 May Day manifesto it argues that "the people of Mexico demand" efforts for "unity capable of overturning the neoliberal policies of the regime." The "ultras" of Political Sciences speak of "the formation of a united front of the people against neoliberalism." So does this "people’s unity" against "neoliberalism" extend to PRI stalwarts Labastida, Madrazo, Bartlett and Roque?

Nationalism and populism also characterize the politics of a host of pseudo-Trotskyist outfits. Umbral, the publication of the Liga de Unidad Socialista (LUS – Socialist Unity League), calls for a "government of people’s power," at the same time as it denounces the militants who shut down the UNAM research institutes as "provocateurs" and says that "the CGH’s turn to the ultraleft…could lead to the partial defeat of the students and the jailing of some of them," i.e., it blames the victims for government repression! The Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores (PRT – Revolutionary Party of the Working People) is a founding constituent of the Cárdenas popular front. The PRT has already put forward this bourgeois politician as its presidential candidate. For its part, the Militant group, which absurdly presents itself as a "Marxist tendency" of Cárdenas’ bourgeois party, demands: "The PRD must decisively join the action and support the UNAM students and SME workers." We already know the way in which the PRD "supports" the student strikers and the electrical workers, attempting to sacrifice them to the government in order to give itself a "respectable" image in the presidential elections.

Although various left-wing groups make criticisms of Cárdenas, their positions do not fundamentally differ from those of the bourgeois PRD. The national-reformist leftists of the CGH plays the same tune of yearning for the "golden days"of the PRI regime, when it called itself "revolutionary nationalist" and financed a broad range of petty-bourgeois "progressive" intellectuals and even a fraudulent "left-wing opposition" on the take. Zedillo’s assault against the UNAM is not simply due to a "neoliberal" policy, which could be changed by a new team in government, but rather reflects the intensified exploitation of the working people coming out of the counterrevolution in the USSR and East Europe. In order to combat this, it is necessary to pose a class struggle for socialist revolution and its international extension, the only way to guarantee free public education and other urgent needs of the exploited and oppressed masses. And for this what is need above all is to forge a revolutionary workers party.

For Part 2 of this article go to The Battle for UNAM, Part II.

To contact the Grupo Internacionalista and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com