June 2005

Bolivia Explodes in Sharp Class Battle

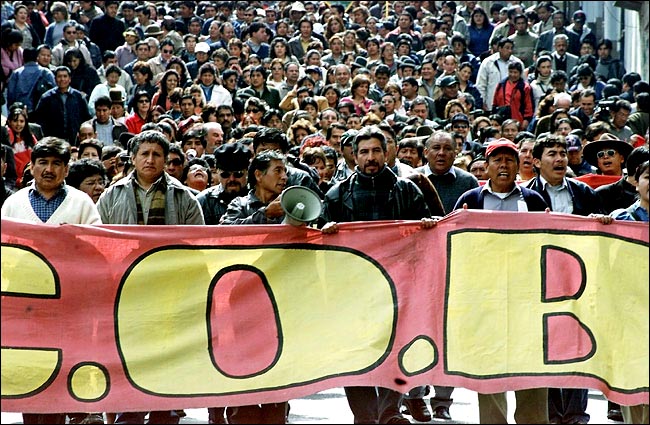

Bolivian

workers of COB union federation march in La Paz, May 17, protesting

approval by Congress

of gas and oil law guaranteeing profits for foreign energy companies

and demanding nationalization.

(Photo:

José Quintana/Reuters)

- Form Workers, Peasants and Soldiers Councils!

- Build the Nucleus of a Genuine Trotskyist Bolshevik Party!

JUNE

1 – After three weeks of

massive mobilizations, tens of thousands of workers and peasants

besieged

Bolivia’s central government plaza yesterday. Throughout the day,

miners

exploded dynamite and riot cops fired tear gas as the demonstrators

fought to

break through police lines to seize the center of La Paz and shut down

the

rightist-dominated Bolivian Congress. Up to 50,000 participated in the

largest

and fiercest protests since the “gas war” of October 2003. Government

spokesmen

threatened repression against labor leaders. The class battle is coming

to a head,

as the choice is posed: advance toward a revolutionary outcome or face

defeat

at the hands of the bourgeoisie, whether in “democratic” guise or

through naked

military force.

JUNE

1 – After three weeks of

massive mobilizations, tens of thousands of workers and peasants

besieged

Bolivia’s central government plaza yesterday. Throughout the day,

miners

exploded dynamite and riot cops fired tear gas as the demonstrators

fought to

break through police lines to seize the center of La Paz and shut down

the

rightist-dominated Bolivian Congress. Up to 50,000 participated in the

largest

and fiercest protests since the “gas war” of October 2003. Government

spokesmen

threatened repression against labor leaders. The class battle is coming

to a head,

as the choice is posed: advance toward a revolutionary outcome or face

defeat

at the hands of the bourgeoisie, whether in “democratic” guise or

through naked

military force.For

the last several days, thousands of slum dwellers poured down into the

capital

from El Alto, the huge impoverished city on the heights above La Paz.

Labor and

peasant groups are blocking roads and highways. In addition to the

indefinite

work stoppage in El Alto, already in its second week, unlimited strikes

have

been called in key cities, including the mining centers of Oruro and

Potosí.

Tin miners have taken their place at the head of protests demanding

nationalization of gas and oil. The slogan “Obreros

al poder” (workers to power) is chanted by miners, teachers and

other sectors,

as working people increasingly talk of revolution. Yesterday, the

leader of the Central

Obrera Boliviana (COB – Bolivian Labor Federation) declared that if

Congress

does not immediately pass a nationalization law, “we are going to burn

it

down at any moment.”

The

protests also oppose rightist demands for “autonomy” of the richest,

“whitest”

departments (provinces) of this predominantly Indian country. Some

leaders of

the peasant movement are demanding that a “constituent assembly” be

called,

which in reality would be a parliamentary escape valve to defuse the

mass

unrest. These self-proclaimed “moderates” want more royalties from the

foreign-owned energy companies, as their ranks are being won over to

the demand

for nationalization. Recalling the army massacre of over 100 protesters

two

years ago, demonstrators chant: “Yesterday, bullets. Today, hunger. The

solution: revolution.” Yet reformist union tops are seeking to use the

mass

radicalization to engineer a “civilian-military” regime, “like Hugo

Chávez” in

Venezuela.

The desperate need of the hour is for

genuinely revolutionary leadership. The splits in the ruling class and divisions

among

the protesters have produced a temporary stand-off. But this cannot

last. Meanwhile sinister

counterrevolutionary forces are

gathering. Graffiti have appeared on the walls of La Paz with slogans

like, “Be

a patriot, kill a unionist.” Mainstream papers like La Razón

taunt

President Carlos Mesa as impotent for fearing that the first “muertito”

(little dead person) could set off an insurrection. Avid plotting by

right-wing

politicians, together with unrest in the armed forces, raises the

spectre of a

military coup. This danger was highlighted yesterday when rightist

congressmen

conspicuously boycotted the scheduled reopening of Congress after a

two-week

“recess,” preventing a quorum.

This

new crisis stems directly from the 2003 “gas war,” when then-president

Gonzalo

Sánchez de Lozada (“Goni”), one of Washington’s regional

favorites, was driven

from power after his savage massacre of demonstrators touched off a

workers

uprising. In the absence of revolutionary leadership, the armed forces

and U.S.

embassy gave power to Goni’s vice president, Mesa. Taking over with

words of

reconciliation, the former journalist sought to divert the rage of

October into

empty democratic ritual. Reformist labor and peasant leaders granted

the new

government an “intermission.” But in the months since Mesa took office,

the

masses have grown more desperate while sections of the ruling class

look for a

“solution of force” to stifle rebellion with an iron hand.

Today,

the workers have taken to the streets vowing to carry out the “agenda

of

October 2003.” Union leaders call to drive out the corrupt and

discredited

parliament, a remnant of Goni’s presidency, and for a “government of

workers,

peasants and the poor.” But what do such calls mean, when they are

maneuvering

with military officials? The League for the Fourth International

insisted then,

as we do today, that the key is forging a revolutionary leadership

fighting on

the program of permanent revolution. As we wrote at the height of the

2003

uprising:

–“Bolivia Aflame: ‘Gas War’ on the Altiplano, Workers to Power!” The Internationalist No. 17, October-November 2003

This

is the revolutionary agenda that is, once again,

sharply posed today.

Class Struggle Over

Gas,

Oil and Power

Contingent

of the combative Regional Workers Center (COR) of El Alto march on May

31.

(Photo: Indymedia/Bolivia)

The

current protests were detonated on May 5, when the Bolivian Congress

passed a

new hydrocarbons (gas and oil) law guaranteeing imperialist energy

conglomerates’ profits. This was the last straw for workers and the

poor in El

Alto, La Paz and other centers where, 19 months earlier, streets ran

red with

their blood in protests against Goni’s sweetheart contracts with the

energy

conglomerates. Fearing mass outrage, Mesa did not sign the new law

himself,

leaving that piece of dirty work to the head of Congress, Hormando Vaca

Díez, a

senator from Santa Cruz who leads a bloc of rightist parties intimately

associated with the deposed Goni.

After

Vaca Díez signed the law on May 17, the expected explosion of

mass discontent

was immediate. Congress fled the capital and Mesa left in what one

paper called

“an operation quite similar to an escape” (Página

12 [Buenos Aires], 25 May). In March, Mesa said he was resigning in

protest

against the “crazy” demands of labor and peasant groups, only to

retract his

resignation and vow to stay in office until 2007. The weakness of this

improvised president has led some bourgeois sectors to ask that early

elections

be called to replace him, while others look towards the army for

salvation.

The

turmoil in Bolivia is generated by two main forces. One is the

increasing

militancy of workers and peasants demanding that the country’s huge gas

and oil

reserves benefit the mass of the population. The other is the

“autonomist” push

by bourgeois forces in the gas-producing eastern and southern regions

to grab

more of the fabulous wealth and keep out the Indian masses of the

highlands

whom these ultra-rightists disdain with undisguised racism. Santa Cruz

was the

base of the military dictators who ruled Bolivia for a decade after

1971.

Living

in poverty for generations, millions of Bolivians feel history has

cheated them

out of the wealth generated by the resources this country has depended

on since

the Spanish Conquest: the silver mines of colonial times that made

Potosí a

synonym for riches; the tin the British and American empires required,

notably for

armaments and canned food during World Wars I and II. Now the vast

reserves of

natural gas are exported for the benefit of “multinational”

(imperialist)

companies – Enron, Shell, British Petroleum, Repsol and others – while

Bolivia

remains the second poorest country of the Americas. Even much of the

middle

class fumes over the centuries of looting of Bolivia.

Behind the

militancy is the feeling that

Carlos Mesa deceived the population with false promises of reform after

taking

over from Goni in October 2003. In July 2004 he held a referendum using

tricky

language to legitimize the gas companies’ super-profits as well as

Mesa’s own

unelected government. He has loyally served the imperialist

corporations and

the American embassy, even getting the Bolivian Senate to approve

immunity for

U.S. troops. Mesa gave in to “autonomy” demands from right-wing

entrepreneurs

in Bolivia’s richest regions, scheduling elections for departmental

governors

in August. Now he is visiting the Army barracks seeking support for a

crackdown

on the rebellious workers, peasants and Indians.

A

key role in propping up Mesa has been played by Evo Morales, leader of

largely

Quechua coca-growing peasants of the Cochabamba region and head of the

Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS–Movements Towards Socialism). Morales has

been

lionized on the left internationally and demonized by right-wing

spokesmen, but

at each crucial juncture his reformist MAS has provided crucial support

to

Mesa. Morales put a phony “anti-imperialist” spin on Mesa’s gas

referendum;

today he plays with words to claim that gas is “already” nationalized

through

royalties and taxes. There are also the envoys sent to La Paz

by the

popular-front government of Lula in Brazil and Peronist Argentine

president

Kirchner, acting as firemen for Yankee imperialism to put out the

flames of

revolution in the region.

As

the MAS tries desperately to curtail the militancy of mass protests,

Morales is

increasingly discredited and has taken to saying “the rank and file

have

outflanked us.” Yet when Carlos Mesa was installed, he received open

support or

an explicit “truce” from the entire

range of labor, slum and peasant leaders – from Morales’ rival in the

peasant

movement Felipe Quispe to Jaime Solares of the COB labor federation and

Roberto

de la Cruz of the El Alto COR union group. Many leftists hailed

“victory”

against Goni. But as we wrote at the time, “toppling the hated

president and

replacing him with his anointed successor [Mesa] is hardly a victory.”

The LFI

denounced “the betrayal by the

misleaders of the workers and peasants – including those who claim to

be

revolutionaries – in granting a ‘truce’ to the new president.” We

pointed out:

– “Bolivian Workers Uprising Knifed, Workers Still on Battle Footing,” The Internationalist No. 17, October-November 2003

Peasamt women carrying the the multi-color wiphala flag of the indigenous movement arriving in La

Paz May 23 after marching from Caracollo to protest energy law. (Photo: Indymedia/Bolivia)

The second motor force of current turmoil comes from the right, with demands for regional “autonomy” raised by the “Civic Committee “of Santa Cruz de la Sierra department in eastern Bolivia, bordering Brazil, and Tarija department bordering Argentina in the south. The Santa Cruz capitalists and landowners are taking a page from slaveholders in the U.S. South by threatening to secede if their demands for even more wealth and power are not satisfied. The more Mesa gives in to them, the more they demand. After the president acceded to their agitation for election of a new governor, they used this to call their own “autonomy” referendum.

While

the Santa Cruz elite sometimes couches its demands in democratic

phrases, they

are openly racist: as one of Bolivia’s “whitest” regions, they want

“autonomy”

from the protests launched by Indian miners and peasants of Bolivia’s

western altiplano

(high plateau). In this

sense, their “autonomy” demands are the very opposite of calls for

autonomy by

oppressed peoples like the Indians of Chiapas, Mexico. What the cruceña bourgeoisie wants is a bigger

slice of the dollar profits from gas and oil production centered in

this

region.

Prominent

in Santa Cruz mobilizations have been the Camisas Negras (black

shirts), shock

troops of a fascistic organization calling itself “Nación Camba”

(Santa Cruz

Nation). Today, armed thugs of the UJC,

the youth group of the Civic Committee, attacked a march of some 500

peasants,

brutally injuring several women, who were demanding nationalization of

hydrocarbons and a constituent assembly. Threats and blackmail from

Santa Cruz

capitalists have been met with indignation by workers and peasants in

the rest

of Bolivia. The “autonomy” demands have also brought condemnation from

members

of the bourgeoisie’s own armed forces, who see them as inimical to

“territorial

integrity.”

Meanwhile,

the regional bourgeoisie faces conflict in its own backyard. Yesterday,

demonstrators in the capital of the department of Tarija took over

congressional delegates’ offices in solidarity with protests on the altiplano. Last month in Santa Cruz,

soldiers and police evicted eighty

families, members of Bolivia’s Landless Peasant Movement (MST), from an

hacienda in the Los Yuquises region. Representatives of the

Guaraní and other

indigenous peoples of Bolivia’s east denounce discrimination by the

local

authorities, stating that if Santa Cruz and other eastern regions get

autonomy,

they want to separate from them.

For

his part, Evo Morales of the MAS is pleading for “consensus” between

the

“agenda” of the La Paz protests and the “agenda” of the Santa Cruz

bourgeoisie.

The mechanism is supposed to be a constituent assembly. The MAS has

long called

for such a body to rewrite the Bolivian constitution, hoping to get a

bigger

slice of power. The promise to call a

constituent assembly was one of the crucial means by which Mesa worked

to

defuse the October 2003 uprising. This is hardly a revolutionary demand

in

Bolivia, which has had at least a dozen constituent assemblies since

independence. The idea that Bolivia’s bitter class struggles

over wealth and power can be resolved through this

supposedly democratic mechanism is a reformist utopia of class peace.

It

is no wonder that the constituent assembly plan is approved by the

World Bank!

This is not a case of popular masses rising up against a dictatorship

or monarchy, or entire sectors excluded from formal parliamentary

democracy, in which calls for a constituent assembly can be

appropriate. What is starkly posed in Bolivia today is workers

revolution or capitalist counterrevolution. The eastern bourgeoisie

seeks to turn its region into a Bolivian version of the reactionary

Vendée which opposed the French Revolution of 1789. They must be

decisively defeated, not conciliated. In Bolivia today, the call

for a constituent

assembly is a counterrevolutionary trap, which must be opposed by

the struggle for a successful workers revolution.

What

is urgent today is to form workers

councils (like the soviets of the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and

1917).

Such councils can draw in the urban and rural poor, indigenous peoples,

youth

and oppressed women, and rank and file soldiers unwilling to carry out

the

murderous orders of the bourgeois officer corps. With social agitation

at a

fever pitch, workers, peasants and

soldiers councils can and should be formed now as a

concrete step to take the struggle forward from the current

stalemate. While the pieces of

dynamite used in demonstrations make a loud noise, they are no

substitute for

the arming of the working class: workers

and peasants militias are crucial to defend the Bolivian working

people

today.

To rip the gas and oil resources out of the

capitalists’ claws, rather than looking to the

parliamentary politicians or a bourgeois nationalization, the working

class “should seize the oil, mining and gas facilities, imposing their

expropriation without compensation and workers control by the ranks of

production and distribution,” as we wrote in 2003.

The

only way out is a workers, peasants and

Indian government based on this proletarian democracy

of workers councils. “Obreros

al poder!” in Bolivia can be transformed from a slogan to a reality

only as

part of the fight for an Andean federation of workers republics,

a

socialist revolution that extends to the workers of the imperialist

centers as

well.

Coup Talk from Right

and

“Left”

Miner

from Caracoles tin mine with dynamite during May 19 protest against

energy law. (Photo:

David Mercado/Reuters)

Miner

from Caracoles tin mine with dynamite during May 19 protest against

energy law. (Photo:

David Mercado/Reuters)Coup

rumors multiply by the hour, centering on the figure of rightist Santa

Cruz

senator Hormando Vaca Díez, who according to the constitution

would be next in

line to succeed Mesa if the president stepped down (just as Mesa put on

Goni’s

tricolor presidential sash when his former boss fled for Miami). Yet

this is

only one variant in the many scenarios for a possible coup

d’état in a country

that had so many military takeovers it was often called “Golpilandia”

(Coup-Land). For almost two decades liberals have spread the illusion

that such

coups are a thing of the past, but the purpose of the capitalist armed

forces

is precisely to use organized violence in defense of the power and

wealth of

the ruling class. It is not for nothing that in Bolivia, the symbol of

the

Military Police is a ravenous bulldog menacingly baring its teeth.

Yet

fatal illusions in capitalist officers and police are spread by leaders

of

workers, peasant and “left” organizations. Evo Morales of the MAS

demagogically

calls for army and police to occupy the oil and gas fields. Jaime

Solares of

the COB has repeatedly called for an “alliance” with “patriotic”

military

officers and support for “an honest military officer like Hugo

Chávez” of

Venezuela. In speeches against last year’s referendum, Solares

grotesquely

boasted of contacts with generals who wanted a tougher line against the

“threat” from Chile (which won Bolivia’s seacoast 125 years ago in the

War of

the Pacific).

Suicidal

illusions in “patriotic military officers” have been put forward as

well by the

Miners Federation leadership, which explicitly hailed two army

colonels, Julio

Herrera and Julio César Galindo, who made a pronunciamiento

on May 26 proclaiming a “Generational Movement” and offering to lead a

civic-military junta in which “we young officers would take charge of

this

country’s government.” Support for a military man on horseback to “save

the

nation” is an old path in Latin America, covered with corpses of the

workers

and oppressed. Most recently in Ecuador, former colonel Lucio

Gutiérrez used

populist demagogy to rope in labor, peasants and the left, only to turn

against

them in the service of Washington and the International Monetary Fund,

as the

League for the Fourth International warned he would do.

COB

officials have also harked back to the 1970-71 Bolivian regime of

General Juan

José Torres – when the left and labor movement formed a “Popular

Assembly”

whose illusions in Torres’ military populism paved the way for the

bloody

rightist coup of Hugo Banzer. This policy of class collaboration

crystallized

in the “Anti-Imperialist Revolutionary Front” (FRA) formed in exile by

Torres,

other officers, and almost all the Bolivian left, most prominently the

main

organization falsely describing itself as Trotskyist, the Partido

Obrero

Revolucionario (POR – Revolutionary Workers Party) of Guillermo Lora.

Today,

POR spokesmen in the leadership of the La Paz teachers union warn

against a

military coup while criticizing illusions in a constituent assembly

preached by

most of the reformist left. Yet the POR has remained deeply committed

to the

strategy of the FRA, even saying this front “could include the entire

police,

as an institution” and demanding “Bolivianization of the armed forces.”

A

smaller centrist organization that calls itself Trotskyist is the Liga

Obrera

Revolucionaria–Cuarta Internacional (LOR-CI – Revolutionary Workers

League-Fourth

International), affiliated to the Fracción Trotskista led by the

Argentine PTS.

The LOR-CI has spread its own illusions in the possibility of the

police

“committing themselves to the defense of the workers and the people” (Lucha Obrera, 24 February 2003).* Its trademark, however,

has been to add the adjective “Revolutionary” to Evo

Morales’ demand for a Constituent Assembly.

Constituent

assembly fetishism follows the tradition of Nahuel Moreno, the

Argentine

pseudo-Trotskyist from whom the PTS/LOR-CI tendency is derived. In the

1980s,

Moreno called for “democratic revolution” in Latin America and for “new

February revolutions,” referring to the February 1917 overthrow of the

tsar.

Genuine Trotskyists fight for new October Revolutions.

In

the recent period the LOR-CI has given increasing emphasis to the call

for a

Popular (or People’s) Assembly. The word popular

is chosen in order to emphasize that such bodies will not be

working-class in character. This is why the Stalinists called their

strategy of

class collaboration the Popular or People’s Front, why Salvador Allende

called

his alliance with bourgeois politicians and “constitutionalist”

officers (including a certain General Augusto Pinochet) the

Unidad Popular, and why reformists the world over, preparing new

defeats, chant

“The people united will never be defeated.”

Demonstrators descend from El Alto

Demonstrators descend from El Alto to La Paz, May 30. Banner reads:

“Expel the Multinationals, Revolution Now!”

(Photo: Indymedia/Bolivia)

The

key lesson of the 1971 Popular Assembly is precisely that it tied the

workers

to Torres, doing nothing to prepare

them against the Banzer coup. On the programmatic level this sellout

was

prepared by the so-called “socialist theses” passed by the COB in 1970,

which

in a deal between the Stalinists, the POR and others, mixed leftist

phrases

with calls for “an anti-imperialist popular front.” Yet today, the

LOR-CI calls

for a program “based on the best contributions of historical COB

documents like

the Theses of Pulacayo and the Socialist Theses of 1970” (LOR-CI

declaration,

21 January).

More

than any other country in Latin America, Bolivia’s political language

has been

influenced by what is widely considered “Trotskyism,” going back to the

Theses

of Pulacayo written by the POR and approved by the miners union in

1946. This

is both a product of, and a factor contributing to, the enormous

combativity

shown by generations of Bolivian workers. Yet at each crucial juncture,

those laying

claim to Trotskyism subordinated themselves to nationalist bourgeois

politicians and military men. That is the opposite of the real content

of

Trotsky’s program of permanent revolution, which addresses just

such

situations as that of Bolivia today.

As

Trotsky concluded from the experience of revolutions in Russia and

China, the

fundamental problems of a semi-colonial country like Bolivia can be

addressed

only through a revolution in which the working class seizes state

power,

supported by the peasantry and the urban poor. Only socialist

revolution can

break the stranglehold of imperialism, resolve the land question

(including

expropriation of landed estates in Santa Cruz, untouched by the

agrarian reform

of Bolivia’s 1952 National Revolution), and win real democratic

rights for

the oppressed, first and foremost Bolivia’s indigenous majority. As

Trotsky

stressed, this permanent revolution must open the road to genuine

socialism – a

classless society of abundance – through its extension to the

industrially

advanced centers of world capitalism.

The

key is to build an authentically communist workers party to head the

struggle.

Neither populist military officers nor a “constituent,” “revolutionary

constituent” or “popular” assembly, but the revolutionary class

power of workers soviets and militias is what is required to

lead the masses of working people, peasants and all the oppressed to

victory

over the dangerous enemies confronting them today. This means a

political

struggle against the current leaders, who seek ever new ways to promote

the old

bourgeois nationalism, playing on the country’s relative geographic

isolation

and remoteness.

The workers of Bolivia are not alone. This new upsurge occurs in the context of

increasing

turmoil in Latin America. In Ecuador, the military populist Lucio

Gutiérrez is

the latest of a series of presidents driven from power in recent years.

In

Brazil, class collaboration has shown its bankruptcy anew as Lula’s

popular

front faces bitter disaffection from the working class. Peru has been

shaken by

a series of local rebellions. Labor strikes and political crises have

wracked

Mexico. In the United States, where workers face the repressive “home

front” of

the imperialist war on Iraq, a dynamic and growing sector of the

working class,

immigrant workers, forms a “human bridge” to upheavals in Latin

America. Only an internationalist perspective,

for extending revolution throughout the Americas and world-wide, can

confront

the danger of imperialist intervention faced by any genuine revolution.

International

socialist revolution was the program of Lenin’s Bolsheviks, who led the

Russian

workers to power under the slogan “All

power to the soviets!” and, with the Red Army led by Leon Trotsky,

defeated

the armed intervention of more than a dozen capitalist powers. This program was carried forward by Trotsky’s Fourth

International, which we fight to reforge.

Leaving

La Paz in October 2003, Bolivia’s miners vowed, Volveremos

– We will return – saying, “If you need to overthrow

someone again, let us know.” The facile analysts who wrote off their

power were

proven wrong yet again. Now the miners have returned, and they mean

business.

It is high time to build the revolutionary leadership, the genuine

Bolshevik

Trotskyist party, crucial to their victory at the head of the heroic

workers

and peasants of Bolivia. n

* In response to our criticisms of its line on the February 2003 police mutiny in Bolivia, the LOR-CI accused us of falsifying their position (in Revista de los Andes, Fall 2004). After being shown quotations from their paper, LOR-CI cadres conceded that our criticism was not only accurate but politically correct. To our knowledge, however, they have yet to publish the correction they vowed to print on this matter.

To contact the Internationalist Group and the League for the Fourth International, send e-mail to: internationalistgroup@msn.com