November 2007

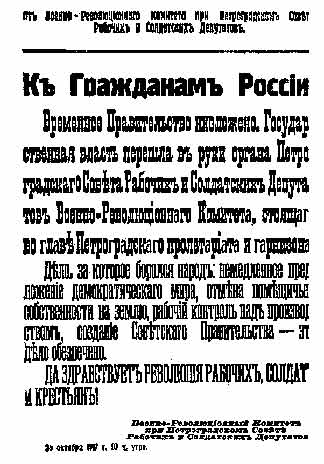

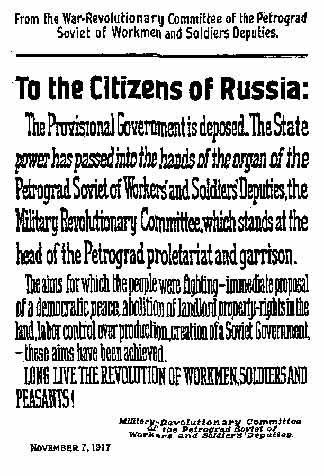

90 Years of the October Revolution

Crack Bolshevik regiment marches on Smolny where Congress of Soviets was meeting under banners

proclaiming “All Power to the Soviets! Long Live the Revolution!”

By Jan Norden

This is the 90th anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917. We commemorate this date – October 25 by the old Gregorian calendar, November 7 by the modern calendar – because it marks an event which was a turning point in world history, and indeed, the seminal event of the 20th century. The March 1917 overthrow of the tsarist autocracy, which ruled the vast Russian Empire, and the victory eight months later of the workers revolution led by the Bolshevik Party, put an end to World War I, the first global imperialist conflagration, and shook the old order from the imperial centers of Europe to the farthest reaches of their colonial “possessions.” The revolution headed by V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky continued to be key to world events for the next three-quarters of a century, long after Joseph Stalin and his bureaucratic henchmen had seized power and betrayed the internationalist program of Red October.

Likewise, the counterrevolution that destroyed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) along with the Soviet-bloc bureaucratically deformed workers states during the period 1989-92 represented a world-historic defeat for the proletariat of the entire planet. Yet contrary to the imperialist ideologues, communism is not dead, we have not entered a “new world order” of peace and prosperity, and we have not reached the “end of history” – far from it. Nor, as a host of self-proclaimed socialists declare, have we been thrown back to the period before October; on the contrary, we must base ourselves on the program and achievements of Lenin and Trotsky. The revolution will rise again, and in order to lead it to victory, this time on world scale, a central task facing revolutionaries today is to draw the lessons both of the victory of 1917 and of the defeat that opened the post-Soviet period.

It is useful to begin with a quote from Karl Marx, in his pamphlet The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852). This was his essay on the defeat of the 1848 Revolution in France and subsequent proclamation of an empire by Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew in December 1851. At the beginning of his pamphlet, Marx wrote:

“Bourgeois revolutions, like those of the 18th century, storm more swiftly from success to success, their dramatic effects outdo each other, men and things seem set in sparkling diamonds, ecstasy is the order of the day – but they are short-lived, soon they have reached their zenith, and a long Katzenjammer [morning-after hangover] takes hold of society before it learns to assimilate the results of its storm-and-stress period soberly. On the other hand, proletarian revolutions, like those of the 19th century, constantly criticize themselves, constantly interrupt themselves in their own course, return to the apparently accomplished, in order to begin anew; they deride with cruel thoroughness the half-measures, weaknesses, and paltriness of their first attempts, seem to throw down their opponents only so the latter may draw new strength from the earth and rise before them again more gigantic than ever, recoil constantly from the indefinite colossalness of their own goals – until a situation is created which makes all turning back impossible.”

Marx was distinguishing the proletarian revolution from the classic bourgeois revolutions, underscoring that setbacks and defeats are an inevitable part of the struggle by the exploited and oppressed to take power from their exploiters and oppressors. A key reason for this is that the bourgeois revolutions of the 18th century marked the taking of political power by a class that was already the dominant class economically. They were delivering the coup de grace, so to speak, to finish off a feudal order that was on the verge of collapse. The proletariat, on the other hand, can establish its economic dominance only after seizing political power and then instituting a socialized, planned economy. Hence, it will always be in a position of relative economic weakness beforehand. That is an important reason why forging a political leadership is far more decisive for the proletarian revolution than for the late bourgeois revolutions.

We look back to Red October of 1917, Krasny Oktyabr in Russian, because it represented the first successful workers revolution in history. It remains the only revolution carried out by the proletariat, whereas many subsequent revolutions (China, Vietnam, Cuba) were based on the peasantry. As James P. Cannon, the founder of American Trotskyism, said in a 1939 speech, “The Russian Bolsheviks on November 7, 1917, once and for all, took the question of the workers’ revolution out of the realm of abstraction and gave it flesh and blood reality” (Cannon, The Struggle for a Proletarian Party). Prior to 1917, the only other attempt by the working class to seize power was the Paris Commune of 1871, which was drowned in blood after barely two months. More than 30,000 Communards were killed in the fighting, and perhaps another 50,000 were executed later by the victorious counterrevolution.

If you think of the impact of the bourgeoisie’s triumphalist cries of the “death of communism” following the demise of the USSR, imagine the impact of tens of thousands dead in 1871. Yet despite the defeat in Paris, not even three and a half decades later you had the Russian Revolution of 1905, which served as a “dress rehearsal” for 1917. Fast forward to 1990, and as the Soviet Union is coming apart, Republican George Bush the Elder proclaims a U.S.-dominated “New World Order.” A few years later, Democrat Bill Clinton’s secretary of state Albright declares the United States to be the “sole superpower,” the supposedly “indispensable power.” Yet barely a decade and a half later, U.S. imperialism is sinking in the quicksands of the Near East while its economy is in crisis, teetering on the edge of a severe recession or new depression.

Why Did the October Revolution Take Place?

So let’s look at the lessons of Red October. In the first place, we should understand why it took place in Russia. Lenin emphasized that the rotting tsarist empire was the “weakest link” in the imperialist chain. It was weak, first, because the autocracy had become a parasitic outgrowth on an economy that was increasingly capitalist. The feudal landed estates had already undergone a considerable transformation with the 1861 Emancipation Edict issued by Tsar Alexander II which formally ended serfdom in response to a series of peasant revolts. Of course, that didn’t mean the peasants escaped from poverty. On the contrary, they were thrown off the land and became vagrants, migrating to the cities. There were all the signs of a dying Old Regime. The court was rife with palace intrigues, with the Tsarina Alexandra (under the influence of the sinister Rasputin) embodying imperial arrogance much as Marie Antoinette did in France on the eve of the French Revolution of 1789. And so on.

But the Russian Empire wasn’t the only dying empire around. The Ottoman Empire was notoriously on its last legs, so much so that it was known as the “sick man of Europe.” World War I led to its demise, with the rise of a series of states in the Near East and the Balkans; its core become modern-day Turkey. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was decrepit, and collapsed in the imperialist world war as well, leaving two rump states, Austria and Hungary, as well as an independent Czechoslovakia, and pieces going to Poland, the Ukraine, Italy and Yugoslavia. So why was the Russian empire the weakest link? Partly because of the tremendous advance of industrial production. Not only was the Ukraine the breadbasket of Europe, exporting huge quantities of grain, but in the industrial centers there were everything from textile plants to giant munitions factories (such as the Putilov Works, the hotbed of revolution), with the most modern production techniques. And along with this you had the growth of an industrial working class.

Most importantly, it was in Russia that the Marxists had produced a revolutionary nucleus that was able to draw numerous lessons from the struggle that aided in achieving the subsequent revolutionary victory. In an essay on “The Russian Revolution and the American Negro Movement,” Cannon observed that Lenin and Trotsky, and the Bolsheviks generally, were able to understand the struggle against black oppression, which is the key question of workers revolution in the United States, because the tsarist empire was a “prison house of peoples,” of a host of oppressed nations, nationalities and pre-national peoples. It was impossible for the proletariat to lead a revolution in Russia without simultaneously championing the cause of these oppressed peoples. In the U.S., on the other hand, prior to the Russian Revolution, even the most left-wing socialists like Eugene Debs declared that “We have nothing special to offer the Negro,” taking a “color blind” position that was blind to the oppression of blacks. Meanwhile, the right-wing socialists included open racists like Victor Berger.

Elsewhere in Europe, at this time, the most militant sectors of the working class were split between revolutionary syndicalists and left-wingers in the parliamentary Socialist parties. The Bolsheviks alone were able to overcome these divisions, partly because the tsarist Duma was a mockery of bourgeois parliamentarism, and because of its impotence didn’t have the power of attraction that the West European legislative talk-shops had. In contrast, in the course of the 1905 Revolution the social democrats had participated in the soviets, or workers councils, leading up to a general strike and the verge of an armed insurrection, which the Bolsheviks were preparing to lead while the Mensheviks recoiled in horror at the prospect. These experiences enabled the Bolsheviks under Lenin and Trotsky to overcome many of the stumbling blocks which had bedeviled the West European workers movement. Finally, Russia was the weakest of the major combatants in World War I, and whereas in the rest of the major powers the social democrats either supported “their own” imperialist bourgeoisies or were paralyzed by impotent pacifism, the Bolsheviks stood for defeat of “their own” imperial masters and called to “transform the imperialist war into civil war,” that is, to fight for social revolution.

So these are some of the social factors that answer the question, Why Russia? But even more fundamental was the “subjective factor,” the existence of a revolutionary leadership. This was organized in the Bolshevik Party, and embodied in the persons of Lenin, who had led the party for almost a decade and a half of turbulent struggles, and Trotsky whose Mezhrayontsi (Interdistrict) group fused with the Bolsheviks in 1917. The Bolshevik party differed from the European social-democratic parties in that it sought to be the party of the proletarian vanguard rather than a “party of the whole class” as advocated by Karl Kautsky. At decisive moments of war and revolution, the reformist pro-capitalist leadership of official Social Democracy held leftist elements in check, even resorting to murder to stave off revolution. In contrast, from the time of his 1902 pamphlet What Is To Be Done? Lenin fought to build a party of the revolutionary minority, a position he initially arrived at empirically and later theoretically generalized. This was decisive.

Even so, in 1917, the Bolshevik “Old Guard” including Lev Kamenev, Grigorii Zinoviev and Stalin stood in the way of proletarian revolution, first calling for “critical support” of the provisional government “insofar as” it “struggles against reaction,” to which Lenin counterposed (in his April Theses) the call for “all power to the soviets” and opposition to the bourgeois government. Then, on the eve of October, Zinoviev and Kamenev opposed an insurrection (unless agreed to by the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries), while Stalin was nowhere to be seen (contrary to the later Stalinist mythology). Lenin and Trotsky, as head of the Petrograd Soviet and its Military-Revolutionary Committee, organized the uprising, and without them, the October Revolution would never have happened. This poses the question of the role of the individual in history. Unlike many bourgeois historians, Marxists do not think that history is made by a series of “great men,” and unlike the Stalinists, we do not engage in hero worship or turn our leaders into icons. At the same time, conditioned by fundamental social forces, at key moments in the class struggle individuals can play a pivotal role. Here is what Trotsky wrote about October 1917, in his Diary in Exile (1934):

“Had I not been present in 1917 in Petersburg, the October Revolution would still have taken place – on the condition that Lenin was present and in command. If neither Lenin nor I had been present in Petersburg, there would have been no October Revolution: the leadership of the Bolshevik Party would have prevented it from occurring – of this I have not the slightest doubt! If Lenin had not been in Petersburg, I doubt whether I could have managed to conquer the resistance of the Bolshevik leaders. The struggle with ‘Trotskyism’ (i.e., with the proletarian revolution) would have commenced in May, 1917, and the outcome of the revolution would have been in question. But I repeat, granted the presence of Lenin the October Revolution would have been victorious anyway.”

But Lenin and Trotsky were there, the October Revolution did take place and instituted a regime based on the soviets of workers and soldiers deputies. In addition to overcoming the opposition of the Bolshevik Old Guard, who clung to the idea that Russia would first have to go through a separate bourgeois revolution before the workers could take power, Lenin elaborated the question theoretically, in his book “The State and Revolution” dealing with “The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution.” Here he elaborated on Marx’s conclusion, based on the experience of the Paris Commune, that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes.” He spelled out how the dictatorship of the proletariat would be realized by a state based on workers councils (soviets), doing away with the parliamentary dens of corruption and pseudo-democracy of periodic elections controlled by money and replacing them through the “conversion of the representative institutions from talking shops into ‘working’ bodies,” of delegates recallable at any time by the bodies which appointed them. Today many would-be Marxists present soviets as purely democratic bodies, while leaving out their vital class content as organs of workers rule.

As Lenin stressed, such soviet rule was infinitely more democratic than most democratic bourgeois state, which is a machine for imposing the class interests of the capitalists. The soviets were not an invention of some idealist thinker but grew out of the 1905 Revolution. And by themselves, they were no guarantee of revolutionary victory. Subsequently, anarchists, bourgeois liberals and White Guard reactionaries joined in praising the soviets while denouncing the communists. “Soviets without Communists” was the slogan of the Kronstadt uprising of 1921 which threatened the very survival of the revolution. Yet if the Bolsheviks had not won the leadership of the soviets, there would have been no October Revolution. The subsequent Stalinist bureaucratization gutted the soviets, at the same time as it destroyed the Bolshevik party that made the revolution. Workers soviets under communist leadership, backed by the mass of the poor peasantry and oppressed peoples, were the key to Red October.

Aftermath of October

The Russian October Revolution led to attempts at workers revolution throughout Europe. One year later, almost to the day, on 9 November 1918, the German workers rose up and overthrew the Hohenzollern monarchy as the Russian workers toppled the Romanov dynasty. There followed uprisings in Bavaria, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, Latvia. The Bolshevik Revolution also sparked a series of revolts among the colonial slaves of Western imperialism. In Europe the social-democratic parties of the Second International, sliding into reformism, failed to champion the cause of the colonial peoples, while the right wing actively participated in colonialism. Even some of the centrists talked of a “socialist colonial policy,” as strange as that may sound today. Not surprisingly, most of these reformists and centrists subsequently supported “their own” bourgeois rulers in the imperialist world war. But when the colonial peoples saw that the Bolsheviks had taken power calling for support to colonial revolts, they responded with enthusiasm. There were uprisings in the Rif (Morocco) and Indonesia, a rapid and explosive development of the Communist Party in China, the beginnings of a CP in India and elsewhere.

From left: Trotsky, Lenin and Kamenev at 1919

Bolshevik party congress.

From left: Trotsky, Lenin and Kamenev at 1919

Bolshevik party congress.Red October had a tremendous impact in every sphere of social life internationally. Much of modern art was deeply influenced by the Russian Constructivists. Modern architecture is almost entirely derived from the experiments in the early Soviet Union, notably the construction of workers clubs and housing, not only emphasizing clean lines and bold designs, but also including social innovations such as reading rooms, recreation and cultural centers. Bauhaus in Germany was a direct reflection of this ferment. The modern cinema was greatly influenced by Soviet filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein, whose movie October (also known as Ten Days That Shook the World, the title of John Reed’s account of the 1917 workers insurrection) we showed to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the revolution. Poster art today is directly derived from the Bolsheviks’ propaganda posters. Even modern typography comes straight from the Soviet Union, where the victorious revolutionaries replaced the elaborate curly-cue letters of the traditional Cyrillic alphabet with modern sans-serif typefaces. Educational reform movements arose throughout West Europe and in the U.S., as well as in Latin America, seeking to drag schools out of their “classical” mold of education for an elite into the modern age of an industrial society which required an educated population. But in Russia these “reforms” were quickly translated into reality, and educational reformists such as John Dewey flocked to Soviet Russia to “see the future.”

Yet these great beginnings never really got past the experimental stage, because of the political counterrevolution that set in under Joseph Stalin and his heirs, who seized power in 1923-24. It was notable that the leaders of this political counterrevolution, the troika or Triumvirate of Stalin, Zinoviev and Kamenev, were the same ones who opposed workers revolution in 1917. The ascendant bureaucracy soon stopped building clubs for workers, for example, because they didn’t want workers to be able to congregate except under its control. The bureaucrats distrusted workers and intellectuals, both of whom had supported Trotsky against the Triumvirate. But more than a simple power struggle was involved. The revolution had occurred in an economically backward, predominantly peasant country, surrounded by more advanced capitalist nations. The Bolsheviks had faced more than a dozen foreign armies. West European imperialists and East European capitalist regimes along with the United States, Japan and China dispatched at least 150,000 troops in expeditionary forces to join with the counterrevolutionary White armies seeking to crush the Bolshevik “Reds.” Following the failure of that intervention, with the Red victory in the 1918-21 Russian Civil War, the imperialists then sought to throw up a cordon sanitaire to quarantine the “Bolshevik bacillus.” This included a diplomatic and economic blockade every bit as ferocious as the U.S. “embargo” that has besieged the tiny island of Cuba for almost half a century since the victory of the revolution there.

On top of this, the series of revolutions in Europe had all failed: the Spartakist Uprising in 1919 in Germany; the short-lived Bavarian and Hungarian Soviet Republics in the same year; 1920 in Italy when the workers in the north took over the factories; also in 1920 the failed Red Army invasion of Poland. Over and over, Germany was the focus of struggle: in 1920, the workers rose up to smash an attempted coup d’état by right-wing nationalists known as the Kapp putsch. in 1921, there was the fiasco of the botched “March Action,” when the inexperienced Communist Party (whose leaders Luxemburg and Liebknecht had been murdered two years earlier) thought it could simply decree a revolution; in 1923, an elaborate plan for a nationwide German uprising went awry, primarily because of contradictory instructions from Moscow, reflecting the opposition of Stalin and his (by then) henchman Zinoviev to carrying out a revolution, while Trotsky did everything possible to push the revolution forward. On the ground in Germany, these conflicting lines led to paralysis and defeat.

Permanent Revolution vs. “Socialism in One Country”

So the combination of economic blockade, the aftereffects of a bloody civil war and the isolation resulting from the failure of the revolution to spread to the European imperialist heartland due to inexperienced leaderships of the young Communist Parties – all of this combined to feed into a growing conservative, nationalist backlash in the Soviet Union. This mood was embraced by the nascent bureaucracy which wanted above all stability so that it could enjoy its new privileges in peace. And it found a spokesman in Stalin, who together with the other members of the troika blocked Trotsky from becoming the central leader of the Bolsheviks upon Lenin’s death in January 1924. When that alliance crumbled, Stalin allied with Nikolai Bukharin, another of the Bolshevik “Old Guard,” to thwart Trotsky. The ideological cover for this anti-revolutionary alliance was opposition to Trotsky’s perspective of permanent revolution, and of the October Revolution’s program of international socialist revolution, in favor of the pipe dream of socialism in one country.

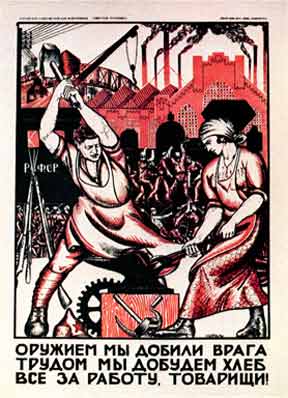

Soviet post-Civil

War poster: “With weapons, we finished off the enemy.

Through labor, we will obtain bread. Everyone to work,

comrades.”

Soviet post-Civil

War poster: “With weapons, we finished off the enemy.

Through labor, we will obtain bread. Everyone to work,

comrades.” We cannot here go into these differences in great detail. Briefly, Trotsky held, based on an analysis of the Russian Revolution of 1905, that in the imperialist epoch, the bourgeoisies in the economically backward capitalist and semi-feudal countries were too weak and too threatened by the spectre of an uprising by workers and peasants that they could not carry out the classic tasks of the bourgeois revolutions: democracy, national liberation and agrarian revolution. Instead, they regularly aligned themselves with the most reactionary forces. The peasantry, on the other hand, lacked the coherent interests and social/economic power of one of the fundamental classes – bourgeoisie or proletariat – and while deeply oppressed, it was not able to lead a revolution. Thus in order to achieve even these basic democratic tasks, it was necessary for the working class to take power, supported by the poor peasantry and other oppressed layers. Having done so, the proletariat would be obliged, if only to preserve the revolution, to undertake socialist tasks by expropriating the bourgeoisie and extending it internationally to the imperialist centers.

This was Trotsky’s early, 1905 formulation of the permanent revolution, a concept that goes back to Marx’s writings after the failure of the 1848 revolutions due to the betrayal of the German, French and Austrian bourgeoisies. And what Trotsky foresaw was what happened in Russia in 1917. That is, the October Revolution positively confirmed the perspective of permanent revolution. A decade later, in 1927, permanent revolution was confirmed in the negative in China when the failure of the working class to take power – due to the prohibition by Stalin and Bukharin imposed on the Chinese Communist Party – led to a bloody defeat at the hands of the nationalist general Chiang Kai-shek. Writing in 1929, Trotsky added one more, crucial, element, namely, that the working class must take power led by its communist party. This was something he had failed to emphasize or fully comprehend in the pre-1917 period, before he joined with Lenin in the course of the revolutionary upheaval, to carry out the program of all power to the soviets over the opposition of the Bolshevik “Old Guard.”

We refer to Trotsky’s perspective of permanent revolution, in order to emphasize that it is simultaneously a theory and a program for action. Quite a few pseudo-Trotskyists refer only to the theory, and don’t see it as a key programmatic question. Many present it as an objective force that will impose itself whether or not the leadership calls for this program. This objectification then serves as a “theoretical” justification for politically supporting petty-bourgeois forces, such as Castroite guerrillas in Latin America and Maoist peasant armies in Asia, on the grounds that, like it or not, they would be obliged to expropriate the bourgeoisie, no matter what their formal programs call for. In reality, the class-collaborationist programs of the Castro and Mao Stalinists have led to defeat after defeat, at a horrendous cost of working-class militants’ lives.

To block Trotsky, in 1924 Zinoviev and others penned rabid denunciations of permanent revolution, and in 1925 Bukharin and Stalin proclaimed the anti-Marxist dogma of “socialism in one country.” Again, it is not possible to elaborate here on this fundamental question. Briefly, as early as 1845, in the German Ideology, Marx declared that “Communism is only possible as the act of the dominant peoples ‘all at once’ and simultaneously, which presupposes the universal development of productive forces and the world intercourse bound up with communism.” Otherwise, he wrote, “each extension of intercourse [i.e., trade] would abolish local communism,” by undermining the isolated workers state with the power of the world market. As Trotsky emphasized, the revolution could break out in a single country, even an economically backward country, but for it to open the door to socialism the revolution must spread to the most advanced capitalist powers. Since a communist or even socialist, classless society can only be built on the basis of generalized prosperity not poverty, Trotsky analyzed in his work, The Revolution Betrayed (1936), seeking to maintain an isolated workers state would require an enormous expansion of police powers to decide who got scarce resources. This is what occurred in the Stalinized Soviet Union, which he termed a bureaucratically degenerated workers state. The subsequent East European regimes that arose following the victory of the Soviet Red Army over Hitler Germany (as well as the Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese and Cuban regimes), modeled on the Stalinist USSR, were bureaucratically deformed workers states from birth.

Under Stalin and the Stalinists, the program of building what they called “socialism” only in the Soviet Union soon was translated into actively opposing revolution elsewhere. After the Stalinists and social democrats let Hitler took power unimpeded in 1933, their panicked response was to launch the popular front. Instead of a workers united front against the fascists, as Trotsky advocated in Germany, the popular front was a class-collaborationist coalition with sections of the bourgeoisie. But the supposed “anti-fascist” (or “anti-imperialist” or “antiwar”) bourgeoisie quickly drops its “democratic” and “progressive” pretenses the minute it sees capitalist class rule threatened. This invariably leads to defeat (often bloody) for the working people, as in the victory of Franco in Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, the triumph of Marshal Pétain in France in 1940, or in the post-World War II period, in the Suharto coup in Indonesia in 1965 and the Pinochet coup in Chile in 1973. Following this logic, Stalin dissolved the Communist International in 1943, as a sop to his imperialist allies in the Second World War.

Defense of the Degenerated/Deformed

Workers States and

Political Revolution to Oust the Bureaucratic Betrayers

Now as Trotsky did, we as Trotskyists defended the Soviet degenerated workers state, as well as the subsequent deformed workers states, against imperialism and internal counterrevolution. Here it is important to distinguish between the class character of a state and its government. By virtue of the expropriation of the bourgeoisie, the USSR was a proletarian regime, eventually basing itself (from the early 1930s on) on a planned economy as opposed to the profit-driven capitalist economy. This economic underpinning could open the way to eventually achieving socialism, even though the political regime of bureaucratic Stalinist rule stood in the way and would have to be swept away by a proletarian political revolution. Trotsky stressed that, although the Stalinist bureaucracy rested on the economic foundations of proletarian rule, and thus was sometimes constrained to defend those foundations, in its bureaucratic manner, the political program of this parasitic layer led it to seek “peaceful coexistence” with imperialism which, since such coexistence is impossible, would ultimately threaten the very foundations of workers power. This helped prepare the way for the restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union and East Europe, and today the same threat of imperialist-sponsored counterrevolution hangs over the remaining deformed workers states of China, North Korea, Vietnam and Cuba.

To help workers in the capitalist countries understand the dialectical concept of a bureaucratically degenerated workers state, Trotsky made a comparison between the Soviet Union under Stalin and a bureaucratically led trade union. Workers must defend the union against the capitalist state, which represents the class enemy, at the same time as they seek to get rid of the sellout misleaders who by their sweetheart deals with the bosses are constantly threatening the existence of the very workers organization they lead. On course, during the anti-Soviet Cold War various reformist social democrats refused to defend the USSR under imperialist attack. By the same token many of them refused to defend bureaucratic-led labor unions against the capitalist state, and often brought in the government and the courts to “clean up” the unions. Class-conscious unionists, on the other hand, insisted that labor must clean its own house.

This was a big issue in the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), the truck drivers union in the U.S. Beginning in the 1950s, the government went after the IBT leadership on all sorts of corruption charges, reaching a crescendo under the Democratic Kennedy administration in the early ’60s. But what was really behind the feds’ vendetta was fear that the Teamsters could tie up freight transportation with a national strike. Their special target was Jimmy Hoffa, who negotiated the first national master freight agreement in 1964, leading to a considerable rise in truckers’ wages. Hoffa once remarked that everything he knew about organizing over-the-road truckers he learned from the Trotskyists who in the 1930s led the Minneapolis Teamsters (and who were jailed during World War II for their opposition to the imperialist war). In the 1970s, a social-democratic outfit was formed called Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) which in the ’80s went to the Labor Department (under Republican Ronald Reagan) to file a suit against the IBT, which was then used to install a “reform” leadership beholden to the government. The result was a sharp decline in truckers’ wages and the ravaging of the pension system.

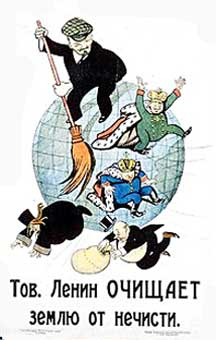

“Comrade Lenin

sweeps the world clean of filth," 1920 Soviet poster.

“Comrade Lenin

sweeps the world clean of filth," 1920 Soviet poster.Same thing with the Soviet Union. The people who claimed that the USSR was “state capitalist” like the anti-Trotskyist renegade Tony Cliff eventually ended up on the barricades with Boris Yeltsin, George Bush the Elder’s “man in Moscow,” in August 1991. These same social democrats, like the International Socialist Organization (ISO) in the U.S., also backed the TDU and others who dragged the unions into the bosses’ courts. So the Cliffites hailed the triumph of counterrevolutionary forces in the USSR proclaiming a “New Russian Revolution.” In Latin America, the followers of Nahuel Moreno, many of whom have now openly embraced “state capitalism,” headlined “Revolution Overthrows Stalinist Dictatorship” and “Great Revolutionary Victory in the USSR.” Well, Russian workers have had to pay the price, through massive impoverishment. The life expectancy for Russian men has fallen sharply as a result, to 59 years, and women have been largely driven out of social labor, denied the right to abortion, and thrown into poverty.

Today, even the Cliffites are forced to admit that the demise of the Soviet Union, which according to them was just a shift from one kind of capitalism to another, is widely seen as a bitter defeat for socialism around the world. It’s interesting to see the gyrations they go through to justify their betrayal with this anti-Marxist, self-contradictory line. An ideologue of the ISO, Anthony Arnove, wrote an article on “The Fall of Stalinism: Ten Years On” (International Socialist Review, Winter 2000) where he starts out saying that the Stalinist regimes were overthrown in East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and the USSR, and declaring “This was a tremendous victory for genuine socialism.” “But,” he adds immediately, “almost universally the opposite conclusion was drawn.” Why so? “For the right, this was obviously a fact to be celebrated,” Arnove writes. Why is that so obvious if it was a “victory for genuine socialism”? Then he goes through various Stalinist-influenced leftists who claim the Soviet bloc states were socialist. While dishonestly claiming that Tony Cliff was “developing the ideas of Leon Trotsky” in declaring in 1948 that the USSR was “bureaucratic state capitalism,” Arnove never mentions that Trotsky called the Soviet Union a bureaucratically degenerated workers state, that Trotsky defended the USSR against imperialism, and that Trotsky fought a faction fight against Max Shachtman over precisely this question.

While claiming that the new ruling classes in East Europe were just the old bureaucrats, he mentions that Lech Walesa of Polish Solidarność headed a new ruling class that imposed market competition and harsh austerity measures, known as “shock therapy,” which eliminated the jobs of many of Walesa’s former supporters in the Gdansk docks. He doesn’t mention that the ISO vociferously supported Walesa’s anti-communist, pro-capitalist, Polish-nationalist, clerical-reactionary movement. So what happened, according to the “state capitalists”? “What happened was actually a step sideways,” he writes. “It was not a transition from socialism to capitalism, but a restructuring of capitalism, similar in fact to the kind of restructuring the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have overseen in Bolivia, Brazil and other countries.” He goes on: “Like everywhere else that capitalism has been restructured, this process has had a devastating impact on the working class.” So when capitalism is “restructured” in Bolivia, Brazil and elsewhere, does the ISO consider that to be a “tremendous victory for genuine socialism”?

Of course, the economy under the Stalinists was bureaucratically planned. The plan called for producing 50 pounds of nails? Ok, they produce one 50-pound nail, as the joke goes. The bureaucrats were fully capable of producing horrendous catastrophes. They drained the water of the Aral Sea in Soviet Central Asia for irrigation of cotton fields, so that today it is reduced to the size of a lake with water so salty that hardly anything can live in it. But this was a conscious decision, and had there been democratic organs of workers rule in charge of the planning, a different decision could have been made. In the case of capitalism, vast disasters such as the more than 200,000 people who were killed in the Asian tsunami of January 2005 or the 100,000 overwhelmingly black and poor people abandoned in New Orleans in Hurricane Katrina that September are the result of the inexorable workings of a system based on maximizing profit. The result of the next tsunami or hurricane, even if there is no Bush in the White House, will be no different.

Let’s consider an example of what a planned economy can do. In 1989-90, we went to East Germany at the time the Berlin Wall opened up. Our organization at that time, the International Communist League (ICL), whose political continuity is the League for the Fourth International (LFI), fought capitalist reunification of Germany tooth and nail, while calling for a political revolution to oust the tottering Stalinist leaders of the DDR deformed workers state. We recruited a number of women comrades. And they took us around their apartments, showing us the rooms for their children, which were guaranteed by law. According to DDR law, children up to a certain age had the right to a room with another child, while teenagers had a right to their own room. On top of this, women had a right to free abortion on demand, which we fight for here. There were low cost communal restaurants, which were not bad; there was free day care, although it was not 24-hours, as we demand, and mothers had to rush home to pick up kids before the closing hour of 6 p.m. Over 90 percent of women had a job, compared to half that percentage in West Germany. While generally excluded from top positions, women played a more prominent role in social life. This was partly due to the fact that East Germany had a tremendous labor shortage from 1945 on. Still, women in East Germany were better off than in West Germany.

The point is that no capitalist country, no matter how advanced its social welfare policies, no Sweden or Norway, has ever or could ever make such achievements a right. The capitalist market economy would not permit it. Every so often, some social democrat comes up with the idea of writing full employment or decent housing or no layoffs into the constitution. Such calls are fundamentally a lie, because there is no way a capitalist country can guarantee such conditions, whether it’s written in a constitution or not. Perhaps for a short period in the wealthiest imperialist country, something approaching full employment could exist, but that will be eliminated with the next recession or depression.

Trotskyism vs. Cold War Social Democracy

So Trotskyists defended the Soviet bloc degenerated and deformed workers states against imperialism and internal counterrevolution, just as the LFI defends China, North Korea, Vietnam and Cuba today, while calling for political revolution to oust the Stalinist misleaders. This meant, for example, defending Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in the 1980s, during the period we called Cold War II. The U.S. financed, armed and trained Islamic fundamentalist mujahedin, including one Osama Bin Laden, to wage “holy war” against the Soviet Army and the weak Afghan reform regime it was propping up. So while the social democrats and “Eurocommunists” joined the imperialists in denouncing a “Soviet invasion,” we hailed the Red Army intervention as a progressive action that could open the way to extending the gains of the October Revolution to Afghanistan as they had been to Soviet Central Asia. The Soviet-backed Afghan government, for example, extended education to girls while the U.S.-backed “holy warriors” shot teachers. But the Kremlin didn’t want this intervention, which it saw forced on it by the CIA’s intrigues, and eventually Gorbachev pulled Soviet troops out in 1989. At that point we offered to send an international brigade to fight on the side of the Kabul regime against the U.S.-backed mujahedin.

We defended the Soviet Union in Poland by opposing the Polish nationalist Solidarność. While the reformist left was joining demonstrations together with monarchists, fascists and social-democratic Cold Warriors proclaiming “Solidarity with Solidarity,” the Trotskyists – which at that time were organized in the international Spartacist tendency – proclaimed “Stop Solidarność Counterrevolution.” We pointed out that Lech Walesa’s Solidarność was union-buster Ronald Reagan’s favorite “union,” that it was financed by millions of CIA dollars funneled through the Vatican Bank and West German social democracy, that it was an anti-Soviet Polish nationalist organization and not a workers union, in which a large part of the membership consisted of prosperous landowning peasants (kulaks), and that Solidarność, after consultation with leading capitalist spokesmen, was in fact calling for counterrevolution in Poland. So, in 1989, Lech Walesa is elected president, Solidarność is in power, and a counterrevolution takes place. Immediately, women are denied the right to abortion.

So, as alluded to, we fought bitterly against counterrevolution, in East Germany and then in the Soviet Union. Then in the International Communist League, we did things no Trotskyists had ever done before. We put out a daily newssheet in East Germany. We ran candidates in the DDR elections. We recruited workers from various plants, including turbine manufacturers like Bergmann-Borsig, and the giant chemical plant at Leuna, the largest in Europe. We issued a call for a massive mobilization against fascist desecration of Soviet workers tombs in Treptow Park in East Berlin, and after the Stalinists joined the united front, a quarter million people, 250,000, overwhelmingly workers, showed up to oppose fascism. This was a threat to the imperialists, who then put their push for capitalist annexation of the DDR into overdrive. The Stalinist leaders saw the spectre of civil war and took fright. So in the space of three months West Germany flooded the country with D-marks and swallowed the DDR into the Fourth Reich of German imperialism.

But although this was a tremendous defeat, we didn’t stop there. We continued to work in Eastern Germany, attracting hundreds of Soviet officers and soldiers stationed in the country to forums on Trotsky’s fight against Stalinism. And we worked in the Soviet Union itself against counterrevolution. One of our comrades, Martha Phillips, was murdered there, a martyr in the struggle for Trotskyism. When Yeltsin seized power in a countercoup in August 1991, we called on Soviet workers to rise up against Yeltsin-Bush counterrevolution. But the rump Stalinists of the “Emergency Committee” ordered workers to stay on the job or at home and not to come into the streets. For they too were looking for a deal with imperialism, as the Stalinists always yearn for. They simply wanted to preserve the USSR, even if capitalism was restored, whereas Yeltsin planned to abolish the Union, and did so six months later.

For working-class revolutionaries today, Red October, is more than just a slogan or an image or a historical reference point. It marks the tasks begun in 1917, which still face us 90 years later. In a forum on the 70th anniversary of the Revolution, in November 1987 at the Leon Trotsky Museum in Coyoacán, Mexico, where the co-leader of the October Revolution and founder of the Red Army was assassinated by a Stalinist agent in August 1940, we noted that “the spectre of Trotsky haunts Gorbachev’s Russia.” While Gorbachev even rehabilitated Bukharin, the father of “socialism in one country” and leader of the Right Opposition, he continued to repeat Stalinist lies about Trotsky, the leader of the Left Opposition. Why? Because the Thermidorean Stalinist bureaucracy feared above all the threat of genuine Bolshevism and its program of world socialist revolution. We cited Leopold Trepper, a heroic Soviet spy and head of the Red Orchestra intelligence group that did invaluable work against the Nazis in occupied Europe. When Trepper was jailed by Stalin after World War II, he wrote:

“Who protested? The Trotskyites can lay claim to this honor … they fought Stalinism to the death, and they were the only ones who did….

“Today, the Trotskyites have a right to accuse those who once howled along with the wolves. Let them not forget, however, that they had the enormous advantage over us of having a coherent political system capable of replacing Stalinism. They had something to cling to in the midst of their profound distress at seeing the revolution betrayed. They did not ‘confess,’ for they knew that their confession would serve neither the party nor socialism.”

Today, most of the international groupings that once claimed to be Trotskyist are assiduously trying to cut their ties to that tradition. The United Secretariat of the Fourth International (USec), once led by Ernest Mandel, wants to unite with the International Socialist Tendency of followers of the late Tony Cliff. The French section of the USec, the Ligue Communiste Révolutionaire (LCR) writes a whole article on the 90th anniversary of the October Revolution without even mentioning Trotsky. This is no accident, as they are preparing to dissolve the LCR into a “broader” party that doesn’t even pretend to be Trotskyist. For them the question of the class nature of China, Cuba, North Korea, etc. or the historical Soviet Union, does not pose a problem because neither the Mandelites or Cliffites defended them at the crucial hour. They joined the social democrats and “Eurocommunists” in “howling with the (imperialist) wolves,” they hailed Yeltsin on the barricades, they are coresponsible for the triumph of capitalist counterrevolution. Likewise the followers of Peter Taaffe in the Committee for a Workers International, the acolytes of the late Ted Grant and Alan Woods who now hail Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and call themselves the International Marxist Tendency, or the followers of Pierre Lambert’s Parti des Travailleurs in France who form the International Entente of Working People – they all renounce building a specifically Trotskyist international party.

In fact, they all look to alien class forces for they have lost confidence, if they ever had it, in the revolutionary capacity of the proletariat. Likewise, those who looked to Stalin and led revolutions in China, Cuba, Vietnam and elsewhere have produced regimes that were nationalist rather than internationalist in their program, and rest fundamentally on a militarized peasantry – a petty-bourgeois force – rather than the working class. Such revolutions could not lead to socialism without a subsequent political revolution, and instead produced bureaucratic regimes that rely on police power to keep the working class in check. Yet those regimes remain fragile because of the contradiction between their actual practice and their formal identification with the October Revolution and their claim (however feeble) to represent workers rule. In contrast to a class, which is rooted in its position in system of production, the bureaucracy is a contradictory petty-bourgeois layer and a parasitic growth on the workers state. When events come to a crisis level there, too, it will be incumbent on authentic Trotskyists to do their utmost to bring the program of Lenin and Trotsky to the workers and youth of those states as it was in the USSR and DDR almost two decades ago.

The fact that various opportunists may claim some vestigial connection to Trotskyism does not alter the rightist character of their centrist or outright reformist politics, often siding with counterrevolution in a “democratic” disguise. The International Communist League, which over several decades represented authentic Trotskyism, argues that the fall of the Soviet Union led to a qualitative regression in proletarian consciousness, whereas the reality is more contradictory. It used this one-sided characterization to justify withdrawing into passive propagandism (while expelling the revolutionaries who went on to form the League for the Fourth International). It responded to a defeat by internalizing a defeatist outlook, and like all revisionists it blames the working class when in fact the leadership is key. Over the last decade, the ICL has embarked on a zigzag course, characteristic of left centrism, marked by capitulation to bourgeois forces at each test. Over China it claimed that the Stalinist bureaucracy was leading the counterrevolution, as if it were some kind of new exploiting class, then retreating from this “third camp” position. Notably, over the U.S. war on Afghanistan and Iraq, the ICL dropped its long-standing call for the defeat of “its own” imperialist rulers while outrageously accusing the LFI of pandering to “anti-Americanism” for upholding this fundamental Leninist position.

For Stalinists, the demise of Soviet Union and East European Soviet-bloc deformed workers states spelled the failure of their whole worldview – which doesn’t stop a few rump Stalinists from running around hailing Stalin, that “great organizer of defeats,” as Trotsky called him. So it’s not surprising that quite a few ex-Stalinists, like the academic Eric Hobsbawm, end up buying into the bourgeoisie’s “death of communism” propaganda, just like their forebears pushed the “god that failed” anti-Communism during the first Cold War. For social democrats, the devastation wrought by the collapse of the USSR is no more problematic than the destruction of “welfare state” social programs in the West – they explain this away by saying it is what is required by capitalism, which they support. For Trotskyists, the counterrevolutionary destruction of the Soviet Union – which we fought against, while the Stalinists capitulated – was predicted long ago, and inevitable unless socialist revolution was extended internationally. Trotsky’s reaffirmation of Marx and Engels’ dictum about the impossibility of an isolated socialism is key to building a new revolutionary vanguard party, which must be Trotskyist or it will not be.

Defeats are inevitable in the struggle for workers rule. What is key is drawing the right lessons from the defeats. This is the point that was underlined by Rosa Luxemburg in her last article, titled “Order Reigns in Berlin,” which she wrote in January 1919, shortly before she was assassinated by the Freikorps precursors of Hitler’s fascists, on orders of the social-democratic government of Friedrich Ebert, Philipp Scheidemann and Gustav Noske. Rosa saw the looming defeat with counterrevolution in the ascendance, but sought to prepare the way for victory:

“Out of this contradiction between the increasingly sharply posed tasks and the insufficient preconditions for resolving them in the early stages of the revolutionary process comes the fact that individual battles of the revolution end in formal defeat. But revolution is the only form of ‘war’ – and this is its particular law – in which the ultimate victory can be prepared only by a series of ‘defeats.’

“What does the entire history of socialism and of all modern revolutions show us? The first flaring up of class struggle in Europe, the revolt of the silk weavers in Lyon in 1831, ended with a heavy defeat; the Chartist movement in Britain ended in defeat; the uprising of the Parisian proletariat in the June days of 1848 ended with a crushing defeat; and the Paris Commune ended with a terrible defeat. The whole road of socialism – so far as revolutionary struggles are concerned – is paved with nothing but thunderous defeats.

“Yet, at the same time, history marches inexorably, step by step, toward final victory! Where would we be today without those ‘defeats,’ from which we draw historical experience, understanding, power and idealism?”

As Marx and Luxemburg underscored, the proletarian revolution advances through a series of defeats, even tremendous defeats, only to come back again, provided that the proletarian revolutionaries draw the correct lessons from these class battles.

To give birth to new October Revolutions, it is necessary to take up the Bolshevik program of 1917, that is, Trotsky’s program of permanent revolution along with his analysis of Stalinism and of an imperialist system sinking further into decay, embodied in the Transitional Program, the founding program of the Fourth International. Contrary to pseudo- and ex-Trotskyist centrists and reformists, we reaffirm that the central thesis of that program, that the historical crisis of humanity is reduced to the crisis of revolutionary proletarian leadership, retains its full validity today. From Mexico to Iraq to the United States, we must build a world party of socialist revolution. This is the program of the League for the Fourth International, of which the Internationalist Group is the U.S. section. As Lenin exclaimed to the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies 90 years ago, “Long live the world socialist revolution!” ■