December 2017

Despite Exemplary Militancy, Failure to

Spread

to the Industrial Proletariat Resulted in a Draw

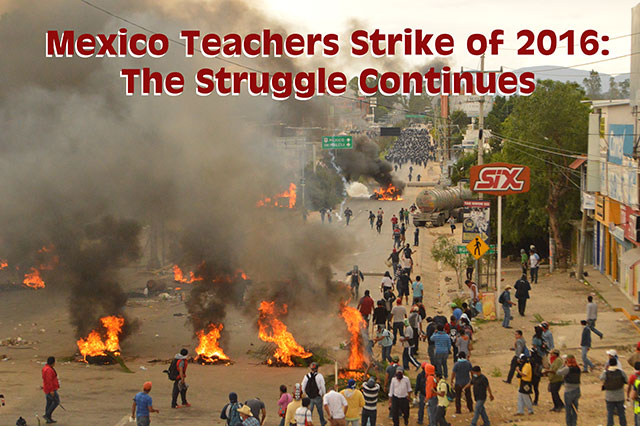

The battle at Hacienda Blanca, 19 June 2016. Even after the massacre at Nochixtlán that day, when cops killed eleven and wounded over 100, teachers and supporters fought federal police in every town on the road to Oaxaca.

(Photo: Revolución Permanente)

Defeat

the Imperialist Assault on Public Education

with Internationalist Workers Mobilization!

The following article is translated from Revolución Permanente No. 7, April-May 2017, published by the Grupo Internacionalista, Mexican section of the League for the Fourth International.

The teachers’ strike that lasted from May to September of 2016 has been one of the sharpest class confrontations in recent Mexican history. On one side, the federal government sought to impose the “educational” counter-reform dictated by imperialist financial agencies. Its purpose was to annihilate public education, eliminate the labor rights of teachers and destroy what it sees as the prime obstacle to these designs: the National Coordinating Committee of Education Workers (CNTE). On the other side, hundreds of thousands of teachers organized in the CNTE in Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guerrero, Michoacán and other states, put up a determined resistance, even against brutal state repression that reached its peak on Bloody Sunday, 19 June 2016, in Nochixtlán, when federal and state police used live ammunition to try to break through one of the highway blockades that had paralyzed the state of Oaxaca.1

As on other occasions, the self-sacrifice and combativeness of the teachers was an example for education workers and other sectors, and not just in Mexico but also beyond its borders. It was truly an epic class struggle. Even before the strike began, the government of President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) thundered ultimatums, echoed by the mass media and spokesmen for big business. Soon it went over to open repression. The striking teachers were demonized as terrorists, privileged and ignorant, but in spite of the avalanche of slander against them, the firm support of the parents, indigenous communities, and in general of the “common people,” gave the teachers the strength to persist and survive.

There was an enormous potential to extend the strike to the education sector nationwide, and from there to key sectors of the industrial proletariat. This was the perspective of the Grupo Internacionalista, which intervened at every stage of the struggle, both in Oaxaca and in the national capital (Mexico City), arguing for a class-struggle program. When the capitalists took aim at public education and tried to finish off an important stronghold of “independent” unionism in Mexico, they were attacking all the exploited and oppressed. There were, and still are, other sectors under government attack, like the oil workers, health workers, etc., who comprised the potential for a working class counter-offensive, at the head of the urban and rural poor, against their repression and starvation at the hands of the bourgeoisie.

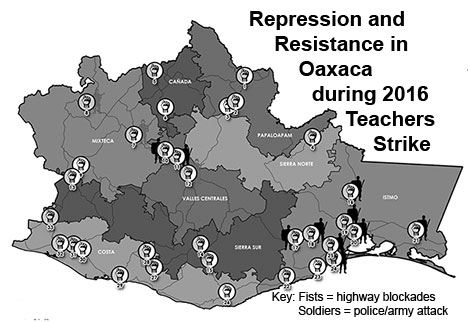

(Map by Subversiones, Avispa Mídia and Oaxaca Libre)

But this road was blocked by a number of obstacles. First among them is that in most of the country, the education workers are still regimented under an apparatus of corporatist control: the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE), a government organization dedicated to preventing independent workers unions. Under the now-deposed chief Elba Esther Gordillo and her designated successor Juan Díaz de la Torre, the SNTE has been the government’s main weapon in imposing and carrying out the education counter-reform. This “labor” front for the capitalist state actively blocked the mobilization of teachers in central and northern Mexico, while in Oaxaca and Chiapas it deployed thugs and paramilitary forces (the infamous gangsters of “Section 59”) to break the strike.

Another important factor was that the “independent” unions, despite occasional empty words of “solidarity,” did nothing to join with the teachers’ struggle. This is a direct result of their leaders playing by the bosses rules: not only do they restrict themselves to the narrowest kind of business unionism, but they adapt to the dictates of corporatist labor law whose function is to prevent proletarian mobilization. Instead of overcoming these barriers, the leaders of the “independent” unions form class-collaborationist alliances with politicians and parties of the bosses, particularly with the PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution) and its offspring MORENA (the National Regeneration Movement) of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, directing unrest in the rank and file into the sterile channels of bourgeois parliamentarism. It was these popular-front alliances that undermined and finally buried the struggle to defend the SME electrical workers union against president Felipe Calderón in 2009.2

Finally, there is the class-collaborationist program of the leadership of the CNTE itself. At the end, the leadership pushed to end the strike on the basis of some vague, verbal promises by the Secretary of the Interior not to go forward with the layoffs called for under the education counter-reform – all made in private meetings with the union leadership of Section 22 in Oaxaca and Sections 7 and 40 in Chiapas, with nothing in writing. This position was consistent with the program of subordination to the bourgeois-populist MORENA, especially in Oaxaca: just as in 2006 when Section 22 backed the same López Obrador (at that time, presidential candidate of the PRD) while state legislators of the PRD called for the intervention of the federal police against the teachers strike; also when [in 2010] the section called for a vote for Gabino Cué for governor, who ended his term under the sign of mass repression and the dead of Nochixtlán; and once again [in June 2016] when it backed Salomón Jara, MORENA’s candidate for state governor.

The teachers’ courageous struggle has at least blocked the implementation of key elements of the counter-reform: in Oaxaca and Chiapas the famous “teacher evaluations” have not been applied, and the threats to fire striking teachers were not carried out. But it was not enough to defeat the attack from the bosses, their parties and their government.

The need to draw a balance sheet of the recent struggles is deeply felt by many teachers. In Section 22, the new state leadership’s idea of a critical evaluation of the experience of the past year is to conclude that demonstrations, work stoppages and strikes are ineffective. In the framework of their strategy of “mobilization-negotiation” they want more “negotiation” and less “mobilization.” This conclusion is false: what is needed is to overcome the limits of localized, trade-union struggle and mobilize the heavy forces of the working class, not to beg the capitalists but to defeat them. And this is perfectly possible.

The courageous teachers, who time and again have resisted riot clubs, tear gas and bullets from police and paramilitary death squads who have killed scores of their comrades need a program for class struggle that points toward international socialist revolution. This is the program embodied in the Russian October Revolution of 1917 whose centenary we celebrate this year, Leon Trotsky’s strategy of permanent revolution that the Grupo Internacionalista fights for today. The GI mobilized to bring this program to the teachers in struggle, at the same time as we addressed other sectors with the perspective of a nationwide strike. The struggle over the anti-education, anti-union “reforms” began with the teachers strikes of 2013. The great battle of 2016 was the second, but still inconclusive act. Now we must prepare a victorious third act, when we finally bury the imperialist-capitalist assault.

Two Lines in the Teachers Strike: Class Collaboration vs. Class Struggle

Women teachers in the front line facing riot police during CNTE blockade of Oaxaca airport, 26 May 2016. Their signs say: “If There Is No Solution, There Will Be a Revolution.” (Photo: Revolución Permanente)

Faced with the government’s cruelty, the teachers mobilization in Oaxaca was not limited to the capital, but shook the entire state. For weeks, almost 40 highway blockades cut the state off from the rest of the country. Federal Police convoys that sought to dislodge the teachers’ plantón (strike encampment) in the center of Oaxaca were stalled for days. When the police finally broke through using live ammunition in Nochixtlán, teachers and poor townspeople flooded the streets to resist. In spite of the massacre, the police encountered mass resistance every ten miles or so, in Huitzo, in Hacienda Blanca, in Viguera, in San Lorenzo. Against the assault rifles of the municipal, state and federal police, the teachers resisted with barricades, sticks and stones. They refused to be cowed by the massacre.

Government repression galvanized the determination of the teachers to fight: they blockaded the airport in the capital and besieged the offices of the state Education Department, the IEEPO. The also blockaded the Santa Maria del Tule fuel depot of the state oil company, PEMEX, for several days. The examples of joint action with the embattled state health care workers were also important, as they carried out work stoppages inspired by the teachers.

From the beginning, CNTE leaders knew that they faced a government that wanted to smash the teachers movement. But the strategy of the leadership was not based on mobilizing a powerful national teachers strike, much less a nationwide strike by the workers. In their speeches, the leadership talked of “walking out together and going back together,” but they settled for a strike limited to Oaxaca and Chiapas, accepting that in Guerrero and Michoacán there would only be intermittent work stoppages, to prevent the militant teachers from being fired. Even though the strike inspired teachers to stop work in Tabasco, Veracruz and even in SNTE strongholds like Monterrey, Nuevo León, the CNTE had no coherent plan for extending the strike.

Harassed and threatened by the government, the CNTE leadership rather than trying to strengthen the strike, instead sought refuge in alliances with a sector of the bourgeoisie. It undertook discussions with representatives and senators from the PRD, which went nowhere. Later, in desperation, it held out its hand to López Obrador. On the eve of the Oaxaca state elections of June 5 last year, the Executive Committee of Section 22 put out a position paper calling for support to MORENA and López Obrador as the only ones who supposedly “supported” the teachers in their struggle against the education reform.

And how would López Obrador “support” the teachers? By promising that he would modify the “education reform” once he was elected president in 2018. In fact, he publicly called on the CNTE not to seek the “repeal” of the education counter-reform. A little later, in mid-July, he insisted that “repeal would be a failure of the government.. this is not good for anyone… We don’t want to build the new Mexico on top of ruins. There must be order and we need to get to 2018 with stability, with social peace… [I]f Peña Nieto is thoroughly beaten, there won’t be stability, there won’t be government” (El Universal, 14 July 2016).

The result of the June 5 elections was a disaster. Within days, the emboldened federal government unleashed open repression, breaking the blockades and arresting the leaders of Section 22. On June 16 the attacks began on highway blockades in Jalapa del Marqués, Juchitán, and Salina Cruz, on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca state. Finally, federal troops tried to break the barricades in Nochixtlán, where they encountered fierce resistance from the primarily Mixtec population. The troops fired indiscriminately. The massacre of Nochixtlán on that bloody Sunday of June 19 left eleven dead and 200 wounded.

The cruelty of the repressive forces immediately unleashed the anger of the population, who reestablished the barricades within hours. On the next day, tens of thousands marched in the state capital to condemn the government’s crimes. The bourgeoisie then proceeded with caution. To cool off the struggle, the government proposed to establish “round tables for dialogue” to seek a “political solution to the conflict” with the CNTE. With the leaders of Section 22 still imprisoned as hostages, the government played at negotiation for weeks, waiting for the movement to wear itself out, so that it could then break off talks and condition their resumption on ending the strike.

The problem wasn’t a lack militancy or capacity to keep the strike going on the part of the teachers. The problem was the leadership, more precisely its program of class collaboration and prostration before the bourgeoisie. For them, the enormous combativeness of the ranks only served to motivate a return to “negotiations,” where they never got anything. The lack of a revolutionary leadership capable of pursuing a strategy of class struggle, seeking to broaden the movement to the rest of the workers movement and to unleash a working-class counteroffensive was alarmingly obvious. And this was no coincidence: the CNTE leadership applied the same strategy in 2013. Although Section 22 is constantly reshuffling its executive posts, the change in personnel does not guarantee any change in the union’s policy.

The Struggle Against Corporatism Requires a Revolutionary Leadership

Elba Esther Gordillo (La Maestra) in 1989 with

Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari when he appointed

her president of the corporatist SNTE teachers pseudo-union in

the basement of Los Pinos, Mexico’s White House. In 2013, she

was arrested by the current president Enrique Peña Nieto on

charges of corruption. Under Gordillo, SNTE gunmen

assassinated scores of dissident teachers. Grupo

Internacionalista called for her to be released so that she

could be tried by a teachers tribunal for mass murder.

Elba Esther Gordillo (La Maestra) in 1989 with

Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari when he appointed

her president of the corporatist SNTE teachers pseudo-union in

the basement of Los Pinos, Mexico’s White House. In 2013, she

was arrested by the current president Enrique Peña Nieto on

charges of corruption. Under Gordillo, SNTE gunmen

assassinated scores of dissident teachers. Grupo

Internacionalista called for her to be released so that she

could be tried by a teachers tribunal for mass murder. The hard experience of the 2016 teachers strike is another demonstration of the need for a class-struggle program to break the shackles of corporatist “unionism.” The SNTE is headed by the charro3 Juan Díaz de la Torre, who was installed at the head of this state-controlled outfit by the very same PRI president Peña Nieto, just as his predecessor and mentor La Maestra Elba Esther Gordillo was by then-president Carlos Salinas (also of the PRI) in 1989. To dismantle public education, the Mexican bourgeoisie must annihilate the CNTE and reestablish the unquestioned authority of the SNTE over all education workers. Hence the government’s praise of the role played by the SNTE throughout the process of imposing the education reform: for example, Juan Diaz de la Torre’s presence at the pompous ceremonies announcing the triumph of the reform alongside Secretary of Education Aurelio Nuño, as well as the funding of the SNTE by the Education ministry to the tune of hundreds of millions of pesos for promotion of the reforms (“Secretariat of Education Gives 550 Million Pesos [US$33 million] to the SNTE to Promote Reform”, El Universal, 4 April).

This is neither an accident nor an occasional anomaly: the SNTE was created in 1943 by decree of president Manuel Ávila Camacho as a government apparatus to control the teachers, who at the time were organized in several dozen education unions. Its founding congress was presided over, funded and organized by the same Ávila Camacho. Its creation was announced in the Mexican Federal Register and applauded by the then-secretary of education Jaime Torres Bodet for embodying “the spirit of unity that all of us Mexicans long for.” Its first general secretary was the former secretary of education, Luis Chávez Orozco. Since then, all its leaders have been imposed directly by the government.

There have been various attempts to organize independently against the SNTE’s corporatism, like the Revolutionary Teachers’ Movement led by the communist teacher Othón Salazar at the end of the 1950s. These efforts met with little success, but in 1979 dissident teachers joined together to form the CNTE in the course of a wave of strikes that reached every region of Mexico. Since then, the CNTE has acted as a dike holding back – sometimes only partially – attacks against education and the teachers. Despite the obsequiousness of CNTE leaders before their executioners, the Mexican bourgeoisie is not satisfied with the political game of give and take that, in part, undercut the insurgent teachers struggles of the 1980s. Now the bourgeoisie is ready to free itself from any hint of resistance to its privatization plans.

Many of the most militant teachers know that they will soon have to return to the streets. But this time resistance will not be enough. What’s needed is a program of class struggle against the bosses, their state and their politicians, based on complete political independence from the bourgeoisie. The current leadership of the CNTE is very far from this perspective. In spite of the attack looming against the teachers, it concludes that the road of mobilization is not to be taken. In the perspectives document for the state convention of the CNTE, in preparation for the national convention held this past March, the leadership of Section 22 declared:

“The experience of the recent days of struggle is constantly moving; it is urgent that we critically revise the forms of struggle that we have put in practice for over 36 years, some of which, due to the duration of the struggle itself and the enemy’s attacks, have become worn out, so that we must proceed together to revise the forms of struggle that we might use in coming days of struggle.”

This summing up dismisses as outworn the “forms of struggle” employed by the dissident teachers movement since its organizational foundation as the CNTE nearly four decades ago. Despite being a conveniently ambiguous declaration, the critique is clearly aimed against mass mobilization and labor strikes. In fact, spokespeople of Section 22 openly declare that the struggle must be “moderated” and that militant mobilizations must be abandoned. The problem, however, is not rooted in the actions characteristic of teacher militancy, but on the contrary in the program that guides them.

In Oaxaca a new mood of struggle can be felt, with a new union leadership that isn’t compromised by the repeated sellouts and betrayals of its predecessors. However, the new leadership wants to justify a program based on canceling (or at least diminishing) mass mobilization, and steering a course of conciliation with the class enemy. When the new state leadership was seated, it began a series of round-table “discussions” with the newly-elected PRI governor Alejandro Murat (son of PRI strongman and former governor José Murat). So what has been the result of these “discussions”?

On December 1 [2016], a mobilization of Section 22 prevented Murat Jr. from being sworn in before the state legislature: he had to do it from the state radio and television studios. Despite the union’s denunciation of his inauguration as illegitimate, as in the past, the teachers’ militant action only served as a prelude to negotiations behind closed doors. The governor agreed to regularize the situation of nearly 3,700 education workers in the face of the refusal of the Secretariat of Education under “Porky Pig” Aurelio Nuño to pay their wages. However, in exchange the union agreed “not to affect the school calendar,” and that the “regularized” employees would first be subjected to the fraudulent “teacher evaluations” that provoked the strike in the first place (Proceso, 7 December 2016). Thus, they offered to let the new governor work in “peace” in exchange for some limited concessions.

For the teachers, the mobilization of key sectors of the proletariat is not an extra luxury, but a necessity. The government is well-known for wearing down the teachers by attrition in order to beat them. This is a product of the social character of the teachers: they are not part of the industrial proletariat, and a strike of education workers does not paralyze the system of capitalist production, nor does it threaten, in itself, the profits of the capitalist class. Contrast the swiftness with which the government moves to cut off strikes in industrial sectors, for example, the strike by steel workers in Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán in March 2016.4

Forge a Revolutionary Workers Party!

Grupo Internacionalista study circle outside Section 22 headquarters during teachers strike, 2 June 2016. During weekly study groups and nightly film showings, GI warned against support to the populist MORENA of López Obrador. Banner reads: “Against Bourgeois Repression, Class-Struggle Mobilization!”

(Photo: Revolución Permanente)

From the beginning of the teachers strike, the Grupo Internacionalista fought for a perspective of extending the strike to the entire education sector and into the workers movement. In the encampments in Mexico City and Oaxaca (where we organized study groups, film screenings, forums, etc.), we brought dozens of striking teachers to appeal to workers of other labor organizations and trade unions to mobilize their power in a joint strike with the teachers. We uniquely defended the need for political independence in relation to the bourgeoisie and its parties PRI, PAN (the clerical-rightist National Action Party), PRD, MORENA, PT (“Labor” Party), etc. From the beginning of the strike we fought against illusions in MORENA, and when the leadership turned to openly using the strike as a vehicle for MORENA’s state electoral campaign, we denounced this as a betrayal.5

This earned us attacks from MORENA loyalists inside the union, who absurdly accused us of being “PRIista provocateurs.” Despite the campaign against us, events proved us right and many teachers who had doubts about the correctness of their leaders began to take our arguments more seriously. Many teacher unionists accompanied us on brigades that we organized to make contact with various sectors of the working class to put into effect our program for the broadening of the strike, against the leadership’s strategy of keeping the strike isolated and limited to negotiations with bourgeois Congressmen and the fictitious “dialogues” with the state ministries.

Our daily work included polemicizing not only against the partisans of MORENA, but also against fake leftists (who even call themselves “communists”) who are instrumental in carrying out the program of collaboration with the bourgeoisie. One of the most influential political forces in Section 22 is the Union of Education Workers (UTE), led by the Stalinists (by definition, defenders of class collaboration with the bourgeoisie) of the Communist Party of Mexico (Marxist-Leninist). The union leadership’s line is almost always a blurred carbon copy of the UTE’s program.

The truth is that the teachers struggle, along with that of the oil workers, miners, steel workers and other trades still under the iron heel of corporatism, as well as the auto workers, telephone workers (now facing a union-busting drive) and all the oppressed, if they are to be victorious, cry out for the forging of an authentic communist vanguard, the nucleus of a workers party armed with a program of internationalist struggle against imperialism, and not another version of bourgeois or petty-bourgeois nationalism that has failed time and again since the failed Mexican Revolution of 1910-17.

To defeat the attack against the teachers, and not simply to trade blows, it is necessary to field a powerful proletarian counteroffensive. The attacks on education and health care, elementary democratic rights, have been sponsored and implemented by the entire Mexican bourgeoisie, the ever-obedient lackeys of the imperialist financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. This shows the impossibility of guaranteeing a free, high quality education to the whole population within the framework of the rotting capitalist system of our epoch. The workers can – and must – defeat the exploiters.

This makes indispensable the theory and program of permanent revolution, formulated and advocated by Leon Trotsky, and confirmed by the Russian Revolution of 1917: in this epoch of decaying imperialism, only the struggle for workers power, for a workers and peasants government, can achieve the most elementary democratic gains, as part of an international socialist revolution. Only a Leninist and Trotskyist revolutionary workers party, a section of a reforged Fourth International, will be capable of leading the workers struggles to victory, extending the revolution to the south and the north, into the very heart of the imperialist beast.

The courageous teachers who have fought with determination for years and decades – and who continue to do so today – deserve a leadership with a program to win. ■

- 1. See “Mexican Teachers Strike Braves Murderous Repression ,” The Internationalist No. 43, May-June 2016.

- 2. See “Life and Death Struggle for Independent Unions in Mexico,” The Internationalist No. 30 (November-December 2009).

- 3. Charro = cowboy. At the beginning of the Cold War, in 1946-48, the Mexican government completed the state takeover of the unions, expelling the “reds” from union leadership positions (jailing many for years), seizing union offices at gunpoint and firing hundreds of union militants. Henceforth, union leaders were directly appointed by the government. The emblematic figure for this corporatist takeover was Jesús de León, who was installed at the head of the railroad workers union and who liked to dress up in Mexican cowboy (charros) outfits with big sombreros and silver decorations. Thereafter the corrupt leaders of these state-controlled corporatist labor organizations, whose task is to prevent the rise of genuine workers unions, were known as “charros.”

- 4. See “The Mexican Steel Workers Strike and the Struggle Against Corporatism,” The Internationalist No. 47 (March-April 2017).

- 5. See “Mexican Teachers Strike Braves Murderous Repression.”