No. 14, January 2018

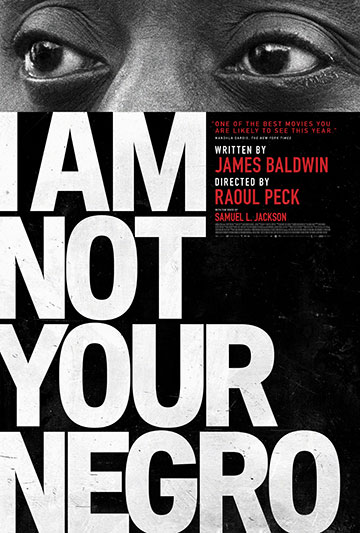

I Am Not Your Negro

James Baldwin in Racist America

By Sarafina, Dan and Abram

Movie poster for I Am Not Your Negro,

directed by Raoul Peck.

Movie poster for I Am Not Your Negro,

directed by Raoul Peck.

I Am Not Your Negro is a documentary film based on two works by the great black gay novelist, playwright and essayist James Baldwin (1924-1987). Members of the CUNY Internationalist Clubs went to see the film when it reached New York movie theaters last spring. The film is important for young revolutionaries to see. It powerfully combines dramatic historical footage and Baldwin’s stirring, courageous denunciation of the centrality of racism to U.S. society. Thus, while the movie doesn’t put forward a revolutionary program – nor does it claim to – what it does do is dramatize crucial issues, including many we studied in our 16-part study-group series on “Marxism and Black Liberation” not long before it came out. So we highly recommend it. In a short review like this, we can only touch on some of the reasons why.

The film is about black oppression in the United States, told through Baldwin’s perspective, and is directed by Haitian-born film maker Raoul Peck. Peck directed the film Lumumba (2000), which tells the story of Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba, from the last months of the bloody Belgian colonial rule in mid-1960 up to Lumumba’s murder by an imperialist-sponsored death squad in January 1961. Peck is also the director of Le Jeune Karl Marx (The Young Karl Marx), which came out in 2017 and portrays the political collaboration and friendship between Marx and Friedrich Engels up to the time they co-authored the Communist Manifesto in 1847.

I Am Not Your Negro is based on James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, “Remember This House,” which tells the story of Baldwin being a “witness to the lives and deaths” of three leading figures in the movements against racist oppression that broke out in the 1950s and ’60s: Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Peck also uses Baldwin’s book-length essay, “The Devil Finds Work,” which uses American cinema as a through-line for Baldwin’s analysis of what the pundits called “race relations.” The documentary is guided by a narration drawing on these two pieces, combined with images from the films he critiqued, video clips and pictures of the civil rights movement and Black Lives Matter protests, as well as footage of Baldwin himself to illustrate his thinking on the problem of racism and its origins.

As a black man living through the age of Jim Crow segregation, Baldwin was particularly concerned with the concept of race in the United States. After spending many years in Europe, he felt obligated to return to the U.S., where racist rampages against integration included white children with signs saying, “We Won’t Go To School With Negroes,” as shown in the movie. In stark contrast, the film shows the striking courage of young black students who were the first to attend a formerly all-white school after segregation de jure (by law) was formally ended through the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision.

During the film, there is a clip of Louisiana Democrat Leander Perez saying, “the moment a Negro child walks into the school, every decent, self-respecting, loving parent should take his white child out of that broken school.” Perez was one of the leading Southern Democrats (called “Dixiecrats”) who supported arch-racist Alabama Governor George Wallace of Alabama in his 1968 presidential campaign. Wallace was the “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” Dixiecrat, who was infamously known for attempting to stop the enrollment of black students at the University of Alabama by physically blocking the front entrance with police.

Racism’s Roots in Soil of American Capitalism

Among the best parts of the film are those showing the blistering intensity of James Baldwin as a speaker and debater unafraid to tell the truth about racial oppression. This, together with his homosexuality, made him a “threat to national security” in the eyes of the FBI. The title of the film changes the N-word to “Negro,” from a 1963 television appearance in which he repeatedly denounced racist America, both North and South, for being unable to answer “why it was necessary to have a ‘n-----’ in the first place, because I’m not a n-----, I’m a man.”

In another scene, filmed three months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, liberal talk-show host Dick Cavett asks Baldwin why black people aren’t “optimistic,” pontificating: “There are Negro mayors. There are Negroes in all of sports. There are Negroes in politics.” Baldwin responds that “it’s not a question of what happens to the Negro here or the black man here” as token or individual figures. He continues, “the real question is what’s going to happen to this country.” Another scene is from the 1965 Cambridge University debate where Baldwin demolished sneering rightist William F. Buckley. Showing that this odious “father of modern conservatism” had plenty in common with Democratic liberal icons like Robert F. Kennedy, Baldwin paraphrased RFK as saying, “in 40 years, if you’re good, we may let [a black man] become president.” As for what’s happened to this country since that time, the election of black Democratic president Barack Obama most certainly did not stem the astronomical rise in the number of black people being thrown in jail and the entrenchment of de facto segregation in big cities. Today, Baldwin’s home town, New York City, has the most segregated school system in the country.

Meanwhile, as Peck highlights in the film, the racist police murder witnessed by Baldwin and denounced by Malcolm X as part and parcel of “the American nightmare” persists today – Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Philando Castile and countless others have been murdered by police and racist vigilantes. On this subject as on many others, the writings of James Baldwin resonate as strongly today as they did during the Civil Rights era.

One of the film’s strengths is its portrayal of Baldwin’s understanding of the interplay between race and class. This included an acute familiarity with how class distinctions within the black population manifested themselves. For example, Baldwin was scathing on how the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the main civil rights organization when he was growing up, “was fatally entangled with black class distinctions, or illusions of the same, which repelled a shoe-shine boy like me.” He was well aware of the difference between black working-class people and black members of the middle and upper-middle classes. Without such an understanding it would be impossible to tackle the double oppression of black working-class people: being ground down and exploited as workers, with all that comes along with that in a capitalist society run for profit, while on top of this being subjugated on the basis of “race.” For U.S. capitalism, though, black workers’ strategic place in capitalist production, transport and communications can be a fatal Achilles heel. Why? Because it’s a source of enormous potential power – which revolutionaries seek to bring to bear in struggle by the multiracial working class to put an end to all oppression.

The film is quite effective in portraying Baldwin’s understanding that racism in the U.S. was not simply a matter of individual prejudice or an innate evil of white people, saying he “did not believe that all white people were devils, and I did not want young black people to believe that.” Baldwin highlighted the fact that the oppression of black people is a systemic phenomenon rooted in the whole history of capitalist America. As a child, he “began to suspect that white people did not act as they did because they were white, but for some other reason.” Though he did not become a Marxist, Baldwin was clearly strongly influenced by the historical materialist outlook. In another clip from the Cambridge debate shown in the film, he points to the material basis of racial oppression, going back to chattel slavery, the historic crime that supported U.S. capitalism’s birth. Racism has its roots in slavery, but it persists long after slavery’s abolition because of the deep-going, systemic inequalities of capitalist America. This has gone on “for so long, so many generations,” Baldwin says, and this material reality continually generates the racist ideology that America’s rulers use to divide the working people. In the face of those who lyingly claim capitalism means freedom, Baldwin points out that “the harbors and the railroads of the country, the economy...could not conceivably be what it has become if they had not had, and [did] not still have...cheap labor.”

Today, the likes of Bernie Sanders pretend this can be overcome through “color-blind” liberalism and tepid reform schemes for a “juster” capitalism under a refurbished Democratic Party. Revolutionary Marxists tell the truth, that only revolution can bring justice, pulling up capitalism’s system of racial oppression by its roots. This requires learning the lessons of history. The Civil War brought the defeat of the slave owners, in large part through 180,000 slaves taking up arms in the Union forces in what Marxists call the Second American Revolution. But after the Northern bourgeoisie sold out Reconstruction, the brief period in which the former slaves won democratic rights, black oppression took on new forms. (See “The Emancipation Proclamation: Promise and Betrayal,” The Internationalist No. 34, March-April 2013.) The system of formalized Jim Crow segregation that consolidated in the late 19th century was targeted by the civil rights upsurge led most prominently by MLK, over half a century later. In the midst of the Cold War, and with U.S. imperialism vying to spread influence in newly decolonized countries of Africa and elsewhere, much of the U.S. ruling class decided that Jim Crow had become a liability.

As part of the program of liberal integrationism and working with the White House, King and other official leaders pledged “non-violence,” even in the face of KKK terror like that which took the life of Medgar Evers. Against this, Malcolm X – who is powerfully though partially evoked in the film – upheld the right of black self-defense and denounced illusions in the Democratic Party. Malcolm’s courageous stand paved the way for the Black Panthers and others who sought a radical answer in light of the clear reality that ending Southern-style legal segregation was very far from ending the racial oppression woven into the economic and social fabric of U.S. society. While many headed into the dead-end illusions of “black nationalism,” a crucial programmatic basis for the struggle to uproot racism was provided by the strategy of “revolutionary integrationism” outlined by veteran Trotskyist Richard Fraser. As summarized the year after Obama’s election, at a time when most of the left was pushing illusions that “black faces in high places” really did mean “hope and change”:

“As opposed to conservative accommodation and liberal integrationism, we Trotskyists fight for a program of revolutionary integrationism. We stress that the fight for black freedom and equality in capitalist America can only succeed by overturning the economic foundations of black oppression. We recognize the radical impulse of many black nationalists who were breaking from the liberal preachers, but emphasize that the oppressed black poor and working people can only achieve power through common struggle together with their class sisters and brothers of all races. We stand for black liberation through socialist revolution.”

– “Barack Obama vs. Black Liberation,” The Internationalist No. 28, March-April 2009

In fighting for this perspective, which is key to building a revolutionary workers party, we are inspired by another aspect that comes through clearly in Peck’s film. That is the passionate, honest search for clarity, the dedication to honest and angular expression, and the aversion to diplomatic hypocrisy embodied by James Baldwin. Hopefully the film will lead those who haven’t done so to read some of his books like The Fire Next Time, Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, Another Country and Notes of a Native Son. When you read them you see, as you do in the film, how despite the many dangers he faced as a black gay man and anti-racist writer very much in the public eye, James Baldwin did his best to find and tell the truth. ■