November 2018

Let Them In! Asylum for Refugees!

Full Citizenship Rights for All

Immigrants!

For Workers Mobilization to Defend Migrants Against Racist

Attacks!

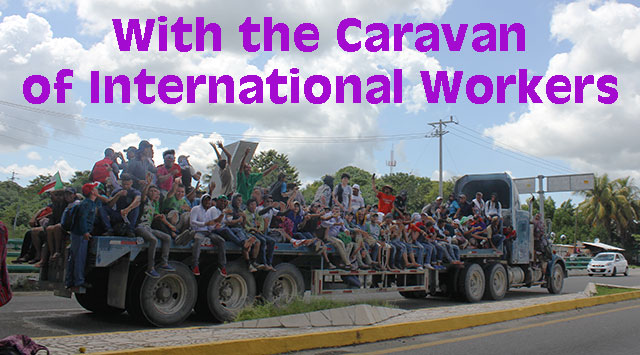

Caravan participants hitch a ride on the road to Huixtla, 21 October. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

By Ulises Méndez

Editor, Revolución Permanente

The following article is translated from a supplement to El Internacionalista, that was distributed at the November 25 actions in solidarity with the Central American caravan.

“And the ‘better life’ that Juan Orlando promised, where is it?” angrily asks Antony Ávarez, one of the thousands of young Central Americans, most of them Hondurans, who make up the caravan which is seeking to reach the southern border of the United States. We are chatting while walking on the highway between Tapachula and Huiztla, Chiapas, the day after the caravan entered Mexico. He is referring to Juan Orlando Hernández Alvarado, known as JOH, who a year ago imposed his reelection as president of Honduras with riot clubs, gas and bullets. Even before then, the country was battered by sky-high levels of poverty, disappearances and murders by the police, and one of the highest homicide rates in the world. It’s the aftermath of the coup d’état of 2009, carried out with Washington’s blessing. Today its fruits are being harvested, causing fear, and sowing rage.

“We were looking for a way to get ahead in Honduras,” Antony remarks, “but you can’t, that’s why we decided to emigrate. You can’t live there any longer. I can’t keep on seeing my family suffer from hunger. We can’t stand it anymore. We want to get ahead, we want another life.” As for the “better life” that the “reelected” Honduran president promised during the election campaign, “we’re going to have to look for it on our own, because there isn’t any back there.”

He’s 24 years old, with a three-year-old daughter and his mother, and his sisters who can’t find work; he was the only one who had a job, as an employee of Diunsa, a department store, but they laid him off after working there for three years. So when he heard on TV that a caravan was heading to the United States from San Pedro Sula – the industrial center of Honduras – he notified his friends on Facebook and called up the closest ones by phone. Eight said they were coming, but in the end only three showed up. The others were overcome by fear, he says. He’s also afraid, but it subsides as he goes along surrounded by thousands of youth who, like him and his friends, are journeying in the caravan, now on the highways of Chiapas after breaching the barrier that the Mexican government erected to try to pin them against the guardrails on the border with Guatemala.

The caravan leaving Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, October 21. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

Actually, it didn’t take a lot of thought to decide to abandon Honduras, the second poorest country of the Western Hemisphere, where 70% of the population is poor, where not even 10% have higher education, and where if you are over 30 it is almost impossible to get a job, not to mention the devastated public health system. The others on the caravan are like him: the unemployed, agricultural day laborers, construction workers, ruined peasants, professionals who can’t find work, the self-employed – businessmen, according to the Honduran president – children under 15, whole families with babies. They are fleeing from hunger, unemployment, crime and the government.

In all of Latin America, only Haiti is poorer than Honduras: more than 65 percent of the population officially lives in poverty, 19% in extreme poverty, on less than $2 a day. It has the highest levels of economic inequality on the continent, as the poorest 40% of the population receives only 10% of the gross domestic product while the richest 10% receives 40% of the GDP. The level of underemployment is up to 60%. Agriculture, the main economic activity, suffered a setback after the collapse of international market prices for bananas and coffee. Not to mention the devastation wrought by Hurricane Mitch in 1998, which led to the destruction of the infrastructure built up over the previous 50 years, of crops, and thousands of people dead and disappeared; and the looting of the country by U.S. and Canadian mining companies that are stripping the native population of their resources.

To that we have to add the ravages of the civil wars, coups and imperialist-imposed authoritarian governments that have beset the “northern triangle” of Central America over the last four decades – that is, for the entire lives of the marchers on the caravan. The death squads of the 1980s were followed by the maras, gangs begun by deportees from the United States, like MS-13 and the 18th Street Gang. These gangs could not operate without the backing of the armed forces and the ultra-corrupt police, both armed by the U.S. After the June 2009 coup, which got the green light from the government of Barack Obama, there was a wave of disappearances and homicides, reaching the level of 86 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011. Even after falling to half that level (43 per 100,000) last year, Honduras is still one of the deadliest countries in the world. Then came the November 2017 election, when protests against the blatant electoral fraud were brutally repressed. (When the opposition candidate was ahead, they simply stopped announcing results for 36 hours.) There were at least 22 civilians killed, and more than 1,300 arbitrary arrests, according to the United Nations, many more according to the opposition. Shortly thereafter, the first big caravan of 2018 departed.

Demonstration against election theft, Tegucigalpa, 18 December 2017. Repression resulted in 22 civilians dead, more than 1,300 arbitrarily arrested. After the protests were suppressed, the caravans began.

(Foto: Orlando Sierra / Agence France-Presse)

“We Are Not Criminals, We Are International Workers”

“There are no job opportunities, it does no good to study because when you graduate, there are no jobs,” says Luis Maldonado, who got hisbachillerato (junior college degree) and in order to survive learned the trade of a barber, but even so couldn’t make ends meet. He assures us that no one instigated them to leave Honduras, as the government of his country and Donald Trump claim. “We simply couldn’t take it any longer: the taxes are too high, the economy is too low, the cost of basic necessities is out of sight. Really, what we made in Honduras was barely enough to feed ourselves day by day, and nothing more.” “The situation is terrible, the government is corrupt, it looted social security, it has looted a lot of institutions which were supposed to benefit the people. We have a corrupt government that oppresses us, it persecutes us and won’t let us be free, as the Constitution says.” “If some politician was behind us, we would be going along very comfortably, but look at the situation we’re in”: it’s already been several hours of walking in the baking sun.

At this point everyone is trying figure out what’s going on with the caravan, how it could be that one caravan among the many that head north from Honduras – at least 30 in the last 15 years – which began with some 600 or 700 people now numbers some 7,000 upon reaching Chiapas, while hundreds more are on the way, trying to catch up. The Honduran government has tried to pin the caravan on Bartolo Fuentes of the Liberal and Refoundation Party (Libre), a group of the “progressive” bourgeoisie which arose after the 28 June 2009 coup which overthrew the Liberal landowner president Manuel Zelaya. First it was called the National Front Against the Coup d’État, which demanded that Zelaya be restored to power; when they didn’t get that, they formed the National Front of Popular Resistance, to bring Zelaya back by the ballot box. Without success.

Juan Orlando Hernández even said that the caravan was convened by “radical left groups,” but that has nothing to do with it either. Bartolo Fuentes himself “accompanied” a caravan of migrants last March, which departed from the city of Tapachula (Mexico) heading to Tijuana, organized by Pueblo Sin Fronteras (People Without Borders). Fifteen years ago, this a group organized the Viacrucis Migrante (Migrant Stations of the Cross) in order to protect those who were migrating from Central America to the U.S. By going in a caravan, participants are able to protect themselves to a degree against organized crime – the thieves, kidnappers and rapists – and the fearsome Mexican immigration police before running into the atrocious U.S. migra, as well as against the xenophobia, class and race prejudice of people who view them with suspicion as they go through their communities. This is one way to get to the north; the others are La Bestia, the dangerous cargo train that leaves from Arriaga, Chiapas, and, if you have enough cash, the coyotes (smugglers).

For Roberto Soriano, “the difference between La Bestia and the caravan is that now we Central Americans are coming united, as brothers and sisters.” “We Hondurans are walking together like a family. If anyone is trying to cause problems with one of us in the caravan, they have to deal with all of us: Honduras, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, people from Nicaragua – they have to take on everyone.” Antony Álvarez puts it this way: “in the caravan you’re not afraid, we have to take advantage of the opportunity of all going together to make our way up there.” He indicates that women are not harassed: “we are all equal for now, no one is better than anyone else – whether you’re from Guatemala, Hondurans, Salvadorans – we’re all in the same boat.”

Unlike previous caravans, which went unnoticed, except by the towns and villages they passed through, the caravan last spring and now this one have gotten an unprecedented boost from Donald Trump via his Twitter account, which he had used to stir up his voters against the “immigrant danger” drawing closer and closer to the border. This rhetoric, incidentally, exposes the servility of the Mexican governments, both the outgoing and the incoming. U.S. vice president Mike Pence even says that Juan Orlando told him that the caravan “was organized by Honduran leftist groups, financed by Venezuela and sent north to defying our sovereignty and our borders.” Once again, no way.

The caravan arrives in Tapachula on the evening of October 20. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

While Pueblo Sin Fronteras accuses the Central American, Mexican and U.S. governments of colluding in order to “attack, arrest and repress [the migrants] with excessive violence,” to criminalize them, and calls upon “students, teachers, transport and other workers, on people in the cities and the countryside” to provide humanitarian aid and to make Mexico a sanctuary country for the Central American immigrants, the fact is that the members of the caravan, sometimes acting as watchmen, don’t refrain from calling on the police to maintain order inside the caravan. They threaten to turn over to the local or immigration police anyone in the contingent caught smoking marijuana or drinking alcoholic beverages.

Notwithstanding the slogan they have taken up on their journey, “migrants aren’t criminals, we are international workers,” the caravan is far from being a march with radical leftist or revolutionary ideology. In fact, what is striking is the religious connotation they give to it. Right from the start, in Honduras, they compared the growing caravan to the biblical exodus led by Moses. Roberto Soriano, who went to the United States six years ago, when he was 17, seeking work, riding atop La Bestia, is migrating this time with the Bible in hand. The story he likes best is that of Moses, because “he brought the people out of Egypt, they put up obstacles and everything, and our god opened the sea for him to pass through with the multitude. When I look on this multitude, I think of all those who are supporting us, those who open their doors to us, so that we can have a better life.” Optimism born of desperation.

Up to Huixtla, the organized support that has aided the caravan has come almost entirely from Catholic and Protestant groups, except for the call of the National Congress of Indigenous Peoples and the Indigenous Governing Council for “urgent solidarity with our brothers and sisters who are suffering forced displacement due to the destruction wrought by big capital in every corner of the world, destruction that is turned into violence, plundering and poverty.” Roberto Soriano says, as do many others, that when the federal police attacked the caravan with tear gas grenades [on the Guatemala border], a six-month-old baby died. “It filled us with rage, and made us want to tear down the gateway, but many mothers started praying and calling on god, so that we calmed down.”

Moreover, many in the caravan distance themselves from those who threw stones at the bloody Federal Police, defending themselves against the tear gas grenades. They insist that they are not criminals, that they are working people who don’t want to bother anyone, that they don’t plan on staying in Mexico, their goal is to head up there to the northern border, and to try to cross it one way or another. They don’t want to be seen as delinquents, or agitators. “This is a peaceful march, we won’t let anyone cause damage, anyone who causes damage is turned over to the police, to any police, any law enforcement.” This occurred in Guatemala where four young men were handed over for allegedly hurting people in the caravan itself, according to Manuel, a Christian day laborer. He says that “joining a peaceful march is not a sin,” and has the support of the pastor of his congregation as well as all his papers: passport, national taxpayer registration and birth certificate. (“Although,” he muses, “from the moment I crossed through the river I violated the law, and the passport won’t do me any good any more, I know that that is breaking the law,” and he smiles to himself.)

In short, what started out as one more caravan ended up being an exodus of Honduran young people which others have sought to use for their own purposes. The Honduran social democrats in order to demand the resignation of the hated JOH, the two-time president who stays in power thanks to the support of Donald Trump, and due to a crude election fraud which even the Organization of American States denounced. Meanwhile, Trump is using the caravan to juice up his electorate, and Chiapas governor Manuel Velasco, an ally of López Obrador, used the occasion to pose as a humanist who placed the government apparatus in the service of the migrants, personally supervising the shelter in Tapachula which the migrants refused to go to because they said it was a trap, since once they got there their cellphones were taken away and they were sent back to Honduras.

The not-so-benevolent reception of the Federal Police for the Central American caravan in Tapachula. The marchers soon learn not to believe in the Mexican government. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

Drawing Lessons from Experience

Víctor Manuel and Josué, agronomy students in the Agricultural Sciences Faculty of the Autonomous University of Chiapas, based in Huehuetán, arrived in Huixtla after a one-hour hike in order to “see with our own eyes the number of people that are coming, we wanted to see if there was a lot of them and if they are bent on aggression, as people are saying on Facebook.” Along the way they noticed how some businesses shut their doors due to the arrival of the Central Americans, but they also saw along the highway how people laid out clothing on the pavement to aid the migrants on the caravan. “Their country is really screwed up, its economy is a wreck,” “their president is finishing them off, that’s for sure.” In Mexico, they say, “things are a little better,” “there is still a way to survive.” (In fact, some people tried to rip them off, like the driver of a bus who, figuring they were migrants, tried to charge them 70 pesos instead of 15.)

Nevertheless, Josué recounts that years ago his father headed north to the United States. His mother was able to get a visa to visit him. When she returned, she told them, “actually, the immigrants really suffer a lot, they don’t have their family members around, the food doesn’t taste the same”; “so we here aren’t aware of that, we enjoy everything the send us, the money, clothes and electronics, but they are suffering there, just as we are here.” She concluded: “I think that this suffering exists everywhere.” Coincidentally, the front page of the local Diario del Sur headlined, “They suffer here and there.” In the background, a photo showing the enormous human column on the highway.

On the road to Huixtla. Walking 3,000 miles in

flip-flops.

On the road to Huixtla. Walking 3,000 miles in

flip-flops. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

A column which has already begun to fragment as it goes along: in the vanguard there are the young people, both women and men, who are bolder, who by hitching a ride are the first to arrive at the next town that is the goal for the day; then come those who are making their way on foot, almost always whole families, or with children in their arms, who can’t benefit from hitching a ride, because then the families would become separated; bringing up the rear are those who walk slowly, or get short rides. There are also those arriving in small waves who belatedly left Honduras and other countries in the region because they knew that they couldn’t pass up this opportunity of the caravan, which far from provoking rejection has received help from local residents: water, food, clothing.

The locals comment that they heard on the radio the call to bring aid. People brought food, blankets, clothing, plastic, boxes. Municipal workers prepared the food, provided medical teams, fixed up areas to sleep; in addition, the local director of education, a school teacher, greeted the migrants from the central plaza of the community and made announcements on the microphone for families and friends who had gotten lost or separated to find each other. But this all fell apart when an unorganized group of young people, with that instinct one gets from being mistreated by the state and its institutions, begins to suspect that things just can’t be that good. So they begin calling on other youth to get the migrants who sought cover in the shelters to leave.

They arrived at the first place that was serving as a shelter, completely full, and call upon the tired marchers to head back to the plaza. It’s a trap, they say. Remember what they did in Tapachula. The authorities deny any such thing, and try to get them to stay, but it’s hopeless. In a matter of minutes, the place emptied. Then, when they see the pick-up trucks of the police loaded with immigrants heading to the second shelter, they call out to get off. “They are cops, it’s a trap, come back!” In the end, they’re all gathered together in the park. One youth who was in the second shelter says that when they arrived, there was no one there to receive them, only bottles of water. Soon the police began to arrive, and the immigration cops, and that’s why they went back running to where the majority were camped out, sleeping in the open, with rain threatening. They are confident that, if they are all together, no one will do anything to them, and if anyone tries, being in an open place, they can get away, unlike the closed places that are serving as shelters.

The hardest lesson: Melvin Josué Gómez died

after falling off a trailer he was trying to climb onto.

(Foto: El Internacionalista)

The hardest lesson: Melvin Josué Gómez died

after falling off a trailer he was trying to climb onto.

(Foto: El Internacionalista)And so, as the caravan moves along, they are drawing lessons from their experiences. They now know, for example, that you can’t trust the Mexican government, because on the bridge from Guatemala they were promised that the border would be opened to let them pass, but instead they were held there for three or four days. They also know that the shelters can be a trap, that “in unity there is strength,” and if they are looking for help, it must only be from their equals, from the common people who come out of their communities to stand along the side of the road offering them water, food, clothes, fruit; those who get out their pick-up trucks to help them on their journey by giving them rides, or jales, as the Hondurans say. The hardest lesson of the day is when 22-year-old Melvin Josué Gómez Escobar, from the region of Chamelón in northern Honduras, died after hitting his head when he fell off a trailer that he was trying to climb onto so that he wouldn’t have to walk so much under the sun that was beating down and caused people to black out. Almost no one stops, they only glance sideways at the body of the young man laid out in a pool of red blood on the black pavement; and they remain silent. Later they tell themselves: better slower, but safer.

Luis Maldonado isn’t getting worked up either, but his silence bothers him.

“I’ve seen worse,” he explains after a while. “I’ve seen how criminals kill people in front of their family, three or four of them, in front of everyone.”

Because that’s the other thing: in addition to the deep poverty and lack of jobs, working people have to pay a “war tax,” what in Mexico is called derecho de piso, or protection money. That was the case with 32-year-old Elia Montoya, who because of her age couldn’t find work. So she set up a little store, to provide for her family, but she wasn’t able to continue because it became unsafe. She and her family were threatened by gangs, and the “war tax” ate up practically all that she earned, on top of which her husband also had to pay part of his wage. So when the caravan passed by, she didn’t hesitate for a moment to leave it all to flee together with her husband, their two daughters and her older sister, who practically had no future at all.

This was also the case of Salomé, a young homosexual, who was travelling with the caravan under the multicolor flag of the gay movement. He joined the caravan because the day before he left five homophobic gang members threatened to kill him, demanding he stop cross-dressing. When they found out he had fled, they threatened two other transvestites, friends of his, who also fled and are now on their way. Or the case of a driver, who had to pay a daily fee to his boss, who only left him with enough for half a meal, and sometimes not that, who came because he had to pay an entire day’s wage per week for the “war tax.” The stories keep repeating themselves all along the highway.

As Nahúm Rodríguez, who used to do electricians jobs, put it: “Honduras no longer has conditions to make possible a decent life: there is unemployment everywhere, as well as crime.” Honduras has the highest murder rate in the entire world, and San Pedro Sula, where the caravan began, is the most violent city on the face of the planet. Moreover, people have been forced to move within the country in an attempt to flee from the gangs, who forcibly recruit children and youths, as well as engaging in human trafficking, above all of women, for prostitution. Even before this exodus, Honduras already pushed out, silently, an average of 300 persons a day.

Turning the Fear Into Wrath

The Grupo Internacionalista organized a demonstration in Oaxaca, October 24, together with Section 22 of the Coordinating Committee of Education Workers (CNTE), in defense of the immigrants of the caravan. Banner calls for “Full Citizenship Rights for All Immigrants.” (Photo: El Internacionalista)

Antony Álvarez sends a message from Arriaga: he’s afraid. He, along with some friends, was pleased because they got a ride that took them one town further, saving almost an entire day. But as soon as they arrived in Arriaga, they had to run to take refuge in a hotel room, which they paid for with the little money they carried with them, to protect themselves from the immigration police who were hunting down the advance guard of the caravan. They feel safe in the hotel room, but not for long, as they get word that the immigration cops are also combing through the hotels to grab them. In fact, it’s all fear: fear of dying of hunger, or at the hands of criminals if they stay in Honduras; fear of the heat beating down, followed by cold downpours which make people sick, above all the children; fear of falling, of falling behind on the road; fear of entering a shelter and ending up deported back to Honduras; fear of being swindled, of people taking advantage of them.

But after Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto announced his plan “This Is Your House,” which “would give them employment opportunities, as well as health care, education and regularizing their status in Mexico,” so long as they stayed in Chiapas or Oaxaca, their new fear is of being trapped in the south, in the two poorest states in Mexico, hoping that the xenophobia being whipped up on social media doesn’t spill into the streets. Nor is there hope that the new government will mean a change of policy. Peña’s plan is in effect an application of AMLO’s proposal to “create swaths of employment in the south of the country so that Mexicans and Central Americans can have work and be happy in the places where they were born and do not have to emigrate.” In that happy and loving world, full of little hearts, the happiest of all would no doubt be Donald Trump, who was not mistaken when he said that the bourgeois populist López Obrador made a better impression on him than the crude capitalist Peña Nieto.

“It’s an investment plan that involves dedicating around $30 billion to the development of Central America and our country in productive projects and creating jobs. It’s a plan like that which President Roosevelt carried out in times of crisis in the United States, which pulled the country out of crisis by providing jobs,” says AMLO (which is false, what ended the Great Depression was World War II). “This is the plan we have for Mexico.” The New Deal that López Obrador was referring to was a program to save capitalism after the crash of 1929, by offering work to, among others, migrant workers, who traveled from one state to another looking for jobs. It was this exodus which was depicted in John Steinbeck’s novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

At bottom, one can pretty much explain the Honduran exodus with words Steinbeck wrote in his book: “The causes lie deep and simply – the causes are a hunger in a stomach, multiplied a million times; a hunger in a single soul, hunger for joy and some security, multiplied a million times; muscles and mind aching to grow, to work, to create, multiplied a million times. The last clear definite function of man – muscles aching to work, minds aching to create beyond the single need – this is man.” In other words, “We want to get ahead, we want another life.” Just like the exodus narrated in the novel, as it goes forward this exodus leaves its dead along the way. “On the highways the people moved like ants, and searched for food, for work.” And just like in the novel, the trucks loaded down with migrants are a cry against capitalist exploitation, which in crisis after crisis tears the masses from their lands and throws them onto the highways, turning them into escape routes to flee from hunger and poverty.

Youth on the Central American caravan in

Tapachula, October 20.

Youth on the Central American caravan in

Tapachula, October 20. (Photo: El Internacionalista)

Thus this exodus of Honduran youth is the result of a free-trade agreement between Central America and the United States, and of the financial crisis which exploded in September 2008 and then intensified with the coup d’état of 2009, when they overthrew Zelaya and took back the subsidies which he had given to the poor. As Yanela Ordóñez, who got herlicenciatura (bachelor’s degree) in education in 2009, in the same year as the coup, explained: “Honduras is going through an exaggerated crisis.” “The coup affected us a lot: they practically privatized education and health care.” From that year on, education deteriorated. It’s practically impossible to fail anyone, even if they have learned nothing. The purpose is to have an illiterate population which doesn’t know its rights and can’t fight for them. The daughter of a day laborer and a housewife, she studied to become a teacher intending to work in public education. But after the coup, those positions were reserved for the hard-core supporters of the regime. She managed to teach in a private school, where they paid her half what a teacher in the public schools earns. Now she is on the caravan together with her husband and her daughter, her sisters, in-laws, nephews and nieces. Having passed the age of 30, she can’t even aspire to work as help in store, where she would earn more than teaching, but which didn’t suit her either.

Looked at carefully, the situation of health care and education in Honduras presages what could happen in Mexico if the so-called education reform is not stopped and the supposed “universalization” of health care is implemented, a swindle that masks the privatization of this vital social service, which is going forward with wind in its sales. In Honduras the upshot is that Hondurans go to Salvadoran or Guatemalan hospitals for treatment, because their own medical system is practically devastated, lacking infrastructure, without supplies or basic medicines, which is now happening throughout Mexico and has been denounced by constant, massive protests by health workers.

Not only that: AMLO’s plan to develop the south involves implementing the so-called “special zones” which would give the green light to pillage by Yankee capital, which is happening now with the “Economic Development and Employment Zones” that Juan Orlando is pushing in Honduras, areas with special laws in the service of capital, with which the Honduran president promised to create 600,000 more jobs. In the same way, López Obrador promises to create 400,000 jobs planting a million fruit trees and timberland in the southeast, along with the jobs produced by building the Tren Maya, the development of the Tehuantepec Isthmus and the modernization of the ports of Veracruz and Coatzacoalcos.

In contrast, the Trotskyists of the Grupo Internacionalista in Mexico, like our comrades of the Internationalist Group in the United States, sections of the League for the Fourth International, have called to let the migrants in the caravan in, to grant asylum to refugees and for all immigrants to have full rights of citizenship, no matter how they got to the country, whether in Mexico or the U.S. We have also called for workers mobilization to defend the immigrants against racist attacks and state repression. And, as always, we do our best to carry out these demands in the course of the struggle for workers revolution on both sides of the northern border, as well as in Central America and beyond.

Meanwhile, thousands of young people trek from one city to the next, seeking to make it to the north, looking for work. As in the Grapes of Wrath, they will find that they have to go from “me” to “we,” to learn the importance of strikes, of the fight against strikebreakers, of the necessary unity of the exploited and oppressed under an internationalist working-class program. Because for these international workers, one day there must be an end to the prayers which quench the fear, but also the wrath. Because what’s involved is turning the fear into wrath that spurs on the struggle for socialist revolution that transcends all the borders of capital. ■