June 2017

U.N. Get Out! Unite with Dominican and U.S. Workers to Smash Imperialism!

Haitian Workers Brave Repression

in Fight Against Starvation Wages

Striking workers from SONAPI industrial park in Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince are blocked by police as they march toward Toussaint Louverture Airport. They are demanding that the minimum wage be more than doubled. (Rapid Response Network)

JUNE 26 – Since the beginning of the year, workers in Haiti have sharply stepped up struggle against the wage-gouging bosses of the garment industry. They have walked out to protest firings of labor organizers and struck for a huge hike in the minimum wage, presently set at 360 gourdes (the Haitian currency), or US$5.50 a day. On May Day, garment workers unions in the four main factory areas announced that they were demanding an increase to 800 gourdes. Even that, more than double the present rate, would only raise daily pay to $12.60, not even remotely enough to live on. But just to win such minimal demands and, more broadly, to combat the starvation wages imposed on Haitian workers by imperialist capitalism requires active solidarity by labor and working people in the United States.

On Friday, May 19, workers in several plants in the SONAPI industrial park in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince walked out demanding 800 gourdes. They set out on a march toward the Presidential Palace, but were stopped by a wall of police. Meanwhile, the bosses’ Association of Industries of Haiti (AIDH) unleashed a barrage of anti-strike propaganda, falsely accusing “militants and trade-unionists” of “beating the workers to get them to leave the plants.” The next day, the bosses closed dozens of plants – a lockout – while 4,000 workers blocked the road to the airport, located next to the industrial park. On Monday, the strike spread to the CODEVI industry park at Ouanaminthe on the border with the Dominican Republic, where thousands walked out, and to plants in the industrial area of Carrefour, just south of the capital (Rapid Response Network, 22 May).

In response, police stepped up repression, firing volleys of tear gas and rubber bullets at strikers. Workers at the SONAPI factory complex returned on May 23, but many just sat at their stations with their arms folded, refusing to sew. At that point the bosses brought CIMO riot police into the plants, where they viciously beat women strikers. Workers fled from the factories, fearing for their lives. Many were arrested, while those who could escape headed to the hall of the SOTA-BO union, which organizes garment workers in Port-au-Prince and Carrefour. That same day, workers at the Caracol industrial park in the north joined the strike, led by their union, SOVAGH, the “Textile Union of Valiant Workers.”

Workers at CODEVI industrial

park walk out on May 22 to join strike for 800 gourde minimum

wage. (Rapid Response Network)

Workers at CODEVI industrial

park walk out on May 22 to join strike for 800 gourde minimum

wage. (Rapid Response Network)SOTA-BO, SOVAGH and SOKOWA in Ouanaminthe are part of the PLASIT-BO coalition of garment unions affiliated with the May First Union Federation led by the leftist Batay Ouvriye (Workers Struggle) syndicalist group. Together the unions kept up “Operasyon Bra Kwaze” (Operation Folded Arms), taking to the streets by the thousands again on May 29. Feeling the heat, the head of the AIDH industrialists association claimed “I have never said I was against adjusting the minimum wage” (Le Nouvelliste, 29 May). He cynically shifted the blame to Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, who, in between jet-setting to Miami, Ecuador and Mexico, said he had no intention of getting involved in discussions about raising the wage.

Moïse passed the buck to the Higher Council on Wages (CSS), whose members he appoints. This is just another trap for labor, to drag out the dispute while workers suffer from the ravages of inflation, particularly of sharply increased prices for transportation and basic necessities. But Haitian garment workers do have power: their labor produces fabulous profits not only for the small-time Korean and Haitian factory owners but for the huge “multinational” corporations who buy their products. The 40,000 workers, overwhelmingly women, in the textile/garment industry produce 90% of Haiti’s exports. On June 16, the unions announced they were pausing the action in order to reorganize for the next round of struggle.

That round will inevitably go up against the imperialists who rule over Haiti, and their flunkey in the presidential palace in Port-au-Prince. More than almost any other country in Latin America, Haiti is run as a neo-colony out of Washington, where the fundamental decisions are made about who will be president, or how little Haitian workers will be paid. But Haiti is also the birthplace of black freedom in the Americas, where the first victorious slave revolution in history sparked uprisings throughout the Caribbean and in the U.S. South. Today the wage slaves of Haiti, joining with their sisters and brothers on the other side of the border that divides the island of Kiskeya/Quisqueya (Hispaniola) as well as with workers in the imperialist heartland, can again become a beacon in the revolutionary struggle to bring down the capitalist masters of the world.

Starvation Wages Imposed by Washington

Wages in Haitian factories are the lowest in the Western hemisphere. And while the daily minimum is supposedly for an eight-hour workday, it is a piece-rate wage and garment workers generally have to work 12 hours or more in order to make the daily quota. That works out to a miserable 45 cents an hour, not even enough to put food on the table. In reality, most Haitian garment workers make considerably less than that. A U.S.-funded survey of 24 of the main garment and textile plants (Better Work Haiti: Garment Industry 6th Biannual Synthesis Report [April 2013]) found that all 24 were out of compliance with the minimum wage law. Another report, by the Worker Rights Consortium, concluded:

“Research conducted by the WRC for this report found that the majority of Haitian garment workers are being denied nearly a third of the wages they are legally due as a result of the factories’ theft of their income.”

–Worker Rights Consortium, Stealing from the Poor: Wage Theft in the Haitian Apparel Industry (October 2013)

Most of the factories are owned by Haitian or South Korean capitalists, but they produce for some of the biggest retailers in the world. Most men’s underwear sold in the U.S. is made in Haiti (Hanes, Fruit of the Loom) as are most women’s bras (Bali, Playtex, Maidenform, Hanes, Wonderbra) as well as many jeans (Levis, Dockers, Calvin Klein, DKNY, Old Navy), sports and college apparel (Champion, Columbia), work clothes (Carhartt) and t-shirts (Gildan, Polo, Aéropostale). These brands are owned by giant corporations with annual revenues of tens of billions of dollars between them. But according to the information in the WRC study, at one plant (Genesis) producing t-shirts for Gildan, which supplies U.S. university licensees, the actual labor cost per shirt for cutting, assembling, sewing and packaging is a little over 2 U.S. cents.

The Haitian unions are demanding that the minimum wage be more than doubled, to $12.60 a day, which if a worker could actually earn that much in an eight-hour workday would amount to $1.57 an hour – still a starvation wage. Another study, by the Solidarity Center of the AFL-CIO union federation, concluded that a “real living wage” allowing one adult worker with two minor dependents to meet basic needs would be $23 a day (The High Cost of Low Wages in Haiti [May 2014]). Even that is an outrageously low figure: a single mother with two children working at a Levis plant would still be living in dire poverty. But the figures on labor costs show that they could raise wages ten times (1000%) and it would raise the production cost of a t-shirt by 18¢.

So this issue has been studied to death, yet absolutely nothing has been done about it. With inflation, Haitian garment workers today are making a dollar less per day than they were in 2014. Why? The plant owners are money-grubbing, wage-gouging cockroach capitalists. The retailers they supply are avaricious mega-capitalists raking in fabulous profits. What else is new? There is a lot of talk about cutthroat competitors from lower-cost producers in, say, Bangladesh. What competition? The corporations who are supplied by both Haitian and Bangladeshi producers are near-monopolies: all the brands cited above belong to a few conglomerates. But beyond that, a key reason Haitian wages are so abysmally low is that the U.S. government wants it that way.

Hillary and Bill Clinton (center) celebrate opening of the SAE-A factory in Caracol Industrial Park, October 2012. The sweatshop garment factory, owned by a notorious Korean union-buster, pays women workers less than $5 a day. Millions of dollars were siphoned by Hillary’s State Department and Bill’s Clinton Foundation from disaster relief funds to build it. (Larry Downing/Getty Images)

In the course of last year’s presidential election campaign, it became more widely known how Bill and Hillary Clinton wreaked havoc with the economy of Haiti (where they spent their honeymoon, after meeting while crossing picket lines at a Yale workers strike). As U.S. president in the 1990s, Bill singlehandedly destroyed Haiti’s rice farming by subsidizing rice grown in Arkansas (where he had been governor). After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, as U.S. secretary of state Hillary siphoned millions from relief funds to finance the industrial park at Caracol, far from the quake zone, anchored by a garment sweatshop owned by SAE-A Trading corporation headed by Woong Ki Kim, a donor to the Clinton Foundation.

When Donald Trump called the Caracol park a giant sweatshop, paid by $400 million in U.S. funds. Democrats were quick to retort. The total paid and budgeted so far for the park and the factory was “only” $370 million. The Washington Post (17 October 2016) wrote that Caracol didn’t fit “our definition of a ‘sweatshop’.” It claimed that “full-time workers are paid at least the minimum wage.” Belying this, a report the Post cited by PolitFact (11 October 2016) said that of workers paid piece-work rates (almost all), “only 41 percent make the government’s target minimum wage.” In fact, the SAE-A plant has consistently paid substantially less than other Haitian manufacturers. Meanwhile, ABC News (11 October 2016) reported:

“In April, a group called Better Work Haiti published a report finding the factory was noncompliant in the areas of sexual harassment, bullying and humiliation of employees. Yannick Etienne, a labor organizer, told ABC News she received reports from SAE-A workers that they had to provide sexual favors to supervisors in order to obtain jobs in the factory.”

So here we have the Walmart and Wall Street feminist icon Hillary Clinton sponsoring a sweatshop paying workers starvation wages where women are subject to sexual harassment, bullying and humiliation. At a Women in the World Summit meeting in New York this past April, held to honor Clinton, the Internationalist Group and CUNY Internationalist Clubs showed up to spoil the celebration with signs proclaiming “Solidarity with Striking Haitian Garment Workers” and “Women Workers Make $5/Day in Hillary’s Haitian Sweatshops.”

Protest outside April 6 Women in the World Summit meeting in NYC to honor Hillary Clinton. (Internationalist photo)

And now Clinton’s former chief of staff Cheryl Mills is partnering with SAE-A chief Kim “to expand the textile trade in Ghana, where BlackIvy [Mills’ consulting company] says the country’s 23-cents-an-hour minimum wage ‘compares favorably’ to higher wages in China, Bangladesh and Vietnam” (New York Times, 17 October). So an SAE-A plant in Ghana could “compete” with SAE-A plants in Vietnam and Haiti by paying half the Haitian minimum wage. That’s globalized capitalism for you. It’s all part of a system: imperialism. And that system depends on state power, particularly on the dominant imperialist power: the United States.

The Clinton connection to low-wage misery in Haiti goes far beyond a single factory in northern Haiti. In previous articles on Haitian workers’ struggles,1 we cited the State Department cables released by WikiLeaks in 2011 showing how the U.S. embassy mounted a major operation to roll back a 2009 attempt to raise the minimum wage to $5 a day. The U.S. chargé d’affaires wrote to his boss (Hillary Clinton) that this “would make the [assembly] sector economically unviable and consequently force factories to shut down” and “would devastate the industry and negatively impact the benefits of the Haitian Hemispheric through Opportunity Partnership Encouragement Act (HOPE II),” which provides for duty-free imports of clothing made in Haiti. It all depends on keeping Haitian wages “competitive” with those in Bangladesh.

Haitian Governments Made in U.S.A.

In addition to derailing legislative initiatives to raise rock-bottom wages, in order to keep the lucrative system of generating superprofits through superexploitation rolling along the bosses need to crush workers’ protests. For the past dozen years, that repression has been the task of the “blue helmet” troops and cops of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). Having brought international condemnation for introducing cholera to Haiti, leading to perhaps 20,000 deaths or more and sickening hundreds of thousands,2 the U.N. finally decided in April to wind down the MINUSTAH. But it will simply be replaced by a new mission, MINUJUSTH, to beef up Haiti’s police.3 Strikers will hardly notice the change.

Meanwhile, Washington has perennially intervened to determine who will lead Haiti. The U.S. invaded Haiti in 1915, kicking off 19 years of brutal occupation.4 Decades later, after the populist priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected president in 1990, he was ousted after eight months in a coup led by CIA-financed intelligence officers under Republican George Bush I. In 1994, Aristide was reinstalled as Haitian president as Democrat Bill Clinton sent in 20,000 U.S. troops, several thousand of whom stayed on until 2000 as “U.N. peacekeepers.” During the next decade, Aristide and his successor René Préval carried out U.S. dictates of privatization and suppression of labor struggles. But in 2004, under Republican George Bush II, the U.S. orchestrated a coup together with France and Canada, sending a snatch team that kidnapped Aristide and bundled him off to the Central African Republic, dropping him on the tarmac.

That led to 13 years of MINUSTAH occupation of Haiti by some 5,000 soldiers and police, acting as mercenaries for U.S. imperialism, which was too busy with its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to send troops. Even with this force to “pacify” the country, the U.S. paid close attention as to who was named president, or not. Despite his earlier services, Aristide was to be kept out. Following the January 2010 earthquake, the U.S. simply took over the country, with thousands of troops and Bill Clinton as U.N. “special envoy.” Haiti’s elected president René Préval was sidelined as “Bill and Hill” ran the show. In the presidential vote that October, Préval’s candidate Jude Célestin came in second. But citing corruption, the U.S. demanded he be removed from the runoff. Hillary Clinton herself flew to Port-au-Prince to lay down the law to Préval.

The victor in the U.S.-rigged February 2011 “selection” was pop musician and son of a Shell Oil executive Michel Martelly, Washington’s favorite, with ties to “Baby Doc” Duvalier (son of long-time dictator “Papa Doc”), who was ousted in a popular uprising in 1986. Martelly was intimately linked to the drug-trafficking Duvalierist death squads whose coup-plotting set the stage for Aristide’s removal in 2004. After a scandal-plagued four years in office, Martelly called legislative elections in August 2015 that were violently broken up by his thugs. An October 2015 first-round presidential election was annulled because of massive fraud. But this time, the U.S. demanded that the second round be held anyway, as the Obama administration supported Martelly’s protégé Jovenel Moïse and had invested $33 million in financing the vote.

Tens of thousands of Haitians took to the streets, and Haiti’s parliament, in a rare (but ultimately empty) show of defiance, ordered the presidential vote to be postponed and an interim government installed. Finally, in November 2016, Moïse, the banana exporter and candidate of Martelly’s PHTK (bald-head) party, won in an “election” in which barely 17% of the electorate voted and 2.4 million voting cards were reported missing. So the U.S. keeps changing horses, it installs and removes Haitian presidents, but there are two constants: under Democrats or Republicans, Washington’s candidate always wins, and Haitian working people always lose. They will continue to lose until a revolutionary leadership is forged to take on and defeat the enormous forces arrayed against them. And that is not the task of Haitian workers alone.

From the Haitian Revolution to International Socialist Revolution

Demonstrators march in Port-au-Prince in June 2010, on sixth anniversary of the occupation of Haiti by United Nations forces (MINUSTAH) on behalf of U.S. imperialism. Sign says: “Down with the Occupation, Down with the Reconstruction Plan, Long Live a Socialist State.” (Photo: Haïti Liberté)

Haiti has been beset by a seemingly endless series of man-made “natural” disasters. It is regularly depicted in the media as a basket case country, a “failed state,” its long-suffering population the object of liberal pity or racist disdain. These disasters are not only compounded by but directly caused by the imperialist system that has consigned Haiti to abysmal poverty. After Haiti threw off French colonial rule in 1804, the European colonizers and the U.S. blockaded the black republic in order to strangle its economy. In 1825 France demanded that Haiti pay 90 million gold francs (almost $29 billion today) to compensate French slave owners for their plantations seized in the revolution. The “debt” eventually passed to National City Bank of New York, and collecting this ransom was the excuse for the 1915 U.S. invasion of Haiti.

In more recent years, the 2010 earthquake that flattened the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince, killing up to half a million people, was met with promises of some $13 billion in aid. Only a small portion of that was ever disbursed, mostly for tent cities and other temporary measures. Some $500 million donated to the American Red Cross disappeared into administrative costs and scams. The money that was disbursed was overwhelmingly done directly by international agencies, by celebrities (Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Sean Penn) or through thousands of “non-governmental organizations” (NGOs) that flocked to Haiti; in this “republic of NGOs” only 1% went to the Haitian government. Most of the 1.5 million living in camps have left, but for hundreds of thousands that just meant moving to precarious hillside slums.5

Since 2010, Haiti has been hit by more calamities. There was the cholera epidemic, started by U.N. occupation troops from Nepal and still continuing. Then in 2015 the government in neighboring Dominican Republic began implementing its racist nationality law, expelling tens of thousands deemed to be of Haitian origin (many of them born in the D.R.). And in October 2016, Hurricane Matthew struck, causing hundreds of deaths and damaging or destroying the homes of half a million people. As a result, in Haiti today there are 55,000 people living in 31 camps near the capital since the 2010 earthquake; many of the 170,000 expelled from the Dominican Republic since 2015 are living in makeshift camps near the border; and 175,000 people left homeless by Hurricane Matthew are in temporary shelters in the south.6

As we wrote at the time, the 2010 disaster was caused by capitalism: the earthquake was predictable and predicted, the collapsed buildings due to shoddy construction caused by Haiti’s poverty, the swollen slums the result of U.S. destruction of Haitian agriculture.7 The League for the Fourth International and our U.S. and Brazilian sections demanded from the very first day that U.S. and “U.N.” troops get out.8 We denounced Washington’s rigging of the 2010 Haitian presidential elections.9 We campaigned for Haitian-Dominican workers solidarity against the mass expulsions in 2015.10 And in October 2016 as the Obama administration barred Haitians at the Mexican border just as Hurricane Matthew hit, the LFI initiated united-front protests in the U.S., Mexico and Brazil to demand an end to exclusion and deportation of Haitians.11

In the face of the colossus of Yankee imperialism, whether the immediate struggle is against starvation wages, racist immigration laws, or repression by imperialist occupiers, the poor and working people of Haiti must not stand alone. The small Haitian proletariat must join with workers across the border in the Dominican Republic and inside the United States to wage a common class struggle. As the Russian Bolshevik Leon Trotsky explained in his theory and program of permanent revolution, in this epoch of decaying capitalism, even to achieve basic democratic gains, it is necessary for the working class to take power and spread the socialist revolution to the imperialist centers. At every turn, the key is to forge a proletarian, internationalist and revolutionary leadership.

A fundamental principle is for total independence from the capitalist state. Haitian workers experience daily how every instance of the neo-colonial state power represents the class enemy. Courts, cops, parliament and government agencies brutally impose the demands of the corrupt and criminal bosses and their imperialist masters. The CSS wage council is a case in point. Formally a “mixed” body with representatives of the employers, labor and the government supposedly representing “the nation,” in reality the government, too, represents the interests of capital. And now Moïse has “reorganized” the council with two out of three “labor” representatives opposed to an increase in the minimum wage, one of them a member of the party of Charles Baker, a leading textile manufacturer.

Batay Ouvriye spokeswoman Yanick Étienne rightly rejected this maneuver as a “delaying tactic” and denounced the president’s “practices of interference” in union affairs (AlterPresse, 1 June). She refused to meet with the “reorganized” wage council, citing the two phony union reps. Two years ago, Yanick Étienne was the target of a vile assassination attempt at the SONAPI industrial park. But for the past period Étienne has herself been a member of the CSS, when the task of class-struggle unionists was to denounce this council of class collaboration as an instrument of the bosses. The failure to do so before undercuts the present struggle for the 800 gourde wage, which must be won against the employers, the president and his hand-picked council.

It is likewise crucial to fight for the political independence of the workers and for a revolutionary workers party. For decades, petty-bourgeois leftists in Haiti and the U.S. have supported the bourgeois-populist Aristide and his Fanmi Lavalas party. Pro-Aristide newspapers like Haïti Liberté have denounced U.S. meddling in Haiti, particularly when Republicans ousted Aristide, but they didn’t complain when Democrat Clinton sent 20,000 U.S. troops to reinstall him in 1994. To break the grip of bourgeois populism, it is necessary to forge a party fighting for the revolutionary class interests of the workers. In early 2016, thousands went into the streets to stop the imposition of of Martelly’s flunkey Moïse, but in the absence of a workers party, new elections would at best install another capitalist president.

Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint Louverture A third vital element is to wage an international class struggle, joining with workers next door in the Dominican Republic and in the United States in particular. At every key juncture, events in Haiti have been intimately connected to world events, beginning with the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804. Haitian nationalists revere the figure of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who declared the country’s independence. But the revolution led by Toussaint Louverture was inspired by and part of the French Revolution of 1789-1802, and it sparked slave revolts throughout the Caribbean and in the American South.12 In fact, it was precisely because of its connection with revolution in Europe that the first slave revolution in history succeeded.

The 1915-34 occupation of Haiti, in turn, was part of the expansion of U.S. imperialism under Republican Teddy Roosevelt and Democrat Woodrow Wilson, including invasions and occupations of Cuba and Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Nicaragua, Honduras, Mexico and elsewhere in Central America and the Caribbean. The second U.S. invasion of Haiti, in 1994, was the result of Democratic Party politics in Washington. The third U.S. invasion, in 2004, by Republican George Bush II, and the subsequent occupation by the MINUSTAH, were a direct result of U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. And the fourth U.S. invasion, following the 2010 earthquake, reflected Democrat Barack Obama’s posture of providing disaster relief to black Haiti while assuaging racists by sending the Coast Guard to block Haitian refugees at sea.

In short, every turning point in Haiti’s history was the result of events in the imperialist centers, and it is there that crucial fights in the next Haitian revolution will be fought. That includes the struggle against the deportation and exclusion of Haitians from the U.S. The “temporary protected status” of Haitians already in the U.S. in January 2010 was recently renewed for six months by Donald Trump’s Homeland Security chief John Kelly, but this only temporarily postpones the inevitable battle. Moreover, Trump’s anti-immigrant offensive also affects many Dominicans in the U.S. New York City is a key place where Haitians (400,000) and Dominicans (600,000) can unite in struggle against their common oppressor, particularly I.C.E. immigration police, providing a potential basis for overcoming the anti-Haitian hysteria in the Dominican Republic.

The importance of an internationalist program is evident even at the level of basic trade-union struggles. Unionized workers at the CODEVI industrial park owned by Grupo M, the Dominican textile giant, should seek to work with unionists at Grupo M plants in the D.R. Workers at the BKI plant at CODEVI, which supplies uniforms to the city of Los Angeles, California should seek ties to labor in L.A. Unionized workers at the SAE-A factory in Caracol, should contact militant trade unionists in South Korea. Potentially there could be a basis for powerful international labor action. But to realize that potential, a leadership with a proletarian internationalist program is needed.

Haitian workers’ battle against starvation wages is the fight of all labor. The Internationalist Group and League for the Fourth International have paid particular attention to Haiti since our inception. In every struggle, we seek to cohere the nucleus of a genuine communist leadership, laying the basis for revolutionary workers parties on both sides of the border that divides Haiti and the Dominican Republic, in the heart of U.S. imperialism and internationally, in the struggle to reforge the Trotskyist Fourth International as the world party of socialist revolution. ■

- 1. See “Haiti: Battle Over Starvation Wages, Neocolonial Occupation,” The Internationalist No. 30, November-December 2009; and “Haiti: Women Workers Strike Against Starvation Wages,” The Internationalist No. 36, January-February 2014.

- 2. A study by the Haitian Ministry of Health released last year covering 4% of the entire population of the country reported that the actual number of deaths in the initial epidemic was almost triple the number reported at the time (New York Times, 16 March 2016).

- 3. The MINUSTAH troops were under the command of Brazilian army generals. The police component of MINUSTAH was led by a Canadian superintendent, with a contingent from the Sûrete de Quebec (provincial police) and the Montréal police. A number of the Quebec police were involved in scandals of sexual misconduct and abuse.

- 4. See “Yankee Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934,” Workers Vanguard No. 608, 14 October 1994.

- 5. Haitian leftist filmmaker Raoul Peck has produced a powerful documentary, Fatal Assistance (Assistance mortelle), exposing the disastrous disaster relief. See also Johnathan Katz, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- 6. U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Haiti Humanitarian Needs Overview 2017.

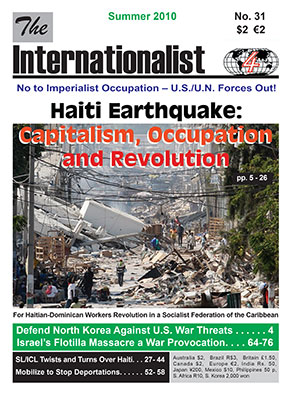

- 7. See “Haiti Earthquake: Capitalism, Occupation and Revolution,” The Internationalist No. 31, Summer 2010.

- 8. “Haiti: Workers Solidarity, Yes! Imperialist Occupation, No!” (January 2010), in The Internationalist No. 31

- 9. “Haiti: Occupation Elections In Times of Cholera,” The Internationalist No. 32, January-February 2011.

- 10. “Stop Expulsion of Haitians from the Dominican Republic,” The Internationalist No. 40, Summer 2015.

- 11. “Haiti Hurricane Disaster: Workers Revolution the Answer,” and “Stop Exclusion of Haitians! Stop All Deportations! Occupation Troops Out of Haiti!” The Internationalist No. 45, September-October 2016.

- 12. See “Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution,” Parts 1 and 2, Workers Vanguard Nos. 446 and 447, 12 and 26 February 1988, available in the Marxist Readings section of www.internationalist.org.