October 2019

Presentations and Comments

at the Trotsky Conference in Havana

Editor’s Note: The following are English versions of the presentations, edited for publication. For the article about the conference, go to: The Havana Trotsky Conference: Notes of a Participant (October 2019)

Trotsky in Mexico:

Anti-Imperialism and Struggle

for the Political Independence of the Working Class

By

Alberto Fonseca

Havana, Cuba, 8 May 2019

Activist of the Grupo Internacionalista, Mexican section of the League for the Fourth International

Leon Trotsky arriving in Tampico, Mexico on 9 January 1937 together wth his companian Natalia Sedova, where they were greeted by by Frida Kahlo. (Photo: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

Leon Trotsky’s arrival in Mexico in January 1937, during the darkest times of the darkest midnight in the century, gave the Russian revolutionary the opportunity to wage his last battles, which were crucial.

Just four months after Trotsky disembarked at the port of Tampico on 9 January 1937, the turning point in the Spanish Civil War occurred with the defeat of the Barcelona May Days. That was when the Popular Front government put down an uprising of the workers. When the workers took over the Barcelona telephone exchange, the Republic’s bourgeois government sent the Assault Guard and the Republican National Guard to oust them, accusing the workers of being in the service of Franco.

What the Stalinists and the Popular Front Government were really doing, with this repression, was to eliminate the workers control that had been established in the most industrialized part of Spain. So a few months after arriving in Mexico, Trotsky was studying the events in Spain, in particular the causes for the defeat of the revolutionary situation that had opened in 1936 with the massive working-class resistance against the coup headed by Francisco Franco.

What Trotsky formulated very clearly is that the popular front is not a tactic, but the greatest crime, as it directly leads to defeat for the struggles of the working class. This is not just a theoretical topic of only academic interest. The question of the popular front is of fundamental importance – and not in Europe alone. It was here in Cuba as well. Because of the treacherous strategy of the popular front, the Partido Socialista Popular, as the Stalinist party was then known, supported the regime of Fulgencio Batista during World War II and joined his cabinet. In Mexico, the politics of the popular front led to the Communist Party turning over the leadership of the newly-formed CTM labor federation to the government of General Lázaro Cárdenas. This ultimately meant integrating the unions into the capitalist state. What the popular-front policy means is collaborating with the class enemy.

Poster for event at the

Trotsky Museum in Coyoacán, Mexico City.

Poster for event at the

Trotsky Museum in Coyoacán, Mexico City.In Mexico, Trotsky also had the opportunity to study a country of belated capitalist development, in which a bourgeois-democratic revolution had begun less than three decades previously. The fact that the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910 remained within the limits of capitalism meant that the democratic tasks that led to it could never be carried through. Today, it is interesting to recall the demands that the revolutionaries in early 20th-century Mexico raised. Take the motto of Francisco I. Madero, “Effective suffrage, no re-election” (in other words, no to electoral fraud): what has happened is that nowadays Mexico is world champion of electoral fraud. Take Zapata’s motto, “Land to the tiller”: the indigenous peasants who got land (overwhelmingly low-quality lands) now have to work as day laborers for the agrobusinesses in northern Mexico, and also on the other side of the border in the United States. Take the always-pending need for the country to free itself from domination by the United States: today Mexico is a U.S. neocolony.

The democratic demands were not fulfilled in Mexico. The Mexican Revolution was aborted. This shows, albeit in a negative way, the validity of the theoretical-programmatic perspective of the permanent revolution. Again, this is not just some theory. In 1938, the government of Lázaro Cárdenas undertook the expropriation of the oil industry. This essentially consisted of expropriating the British companies that extracted oil in Mexico. The British imperialists declared a boycott against Mexican oil. They accused the Mexican government of being in the service of Hitler, since it had to sell oil to Nazi Germany.

Trotsky called on the workers of the world to defend this nationalization carried out by Mexico. He considered it an elementary measure against imperialism. He pointed out the importance of defending this semi-colonial country against imperialist reprisals. Did this mean that Trotsky supported the Cárdenas government? No. To the contrary, he insisted on the need to build an independent, revolutionary workers party. He emphasized the ABC of Marxism: the workers maintain complete class independence from the bourgeoisie. This was precisely the opposite of the policy put forward by the Stalinists, who were forming a popular front, an alliance of class collaboration with the Cárdenas government. In fact, the Stalinists wanted to join the ranks of the Partido de la Revolución Mexicana (PRM), as the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) was called under Cárdenas. The PRM, to be clear, was a party of the bourgeois state. Since Cárdenas did not allow the Stalinists to join the ranks of his party, the Communist Party acted as an external satellite of the PRM/PRI.

We see the popular front policy at work again in Mexico when left organizations support one or another bourgeois caudillo: Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, Andrés Manuel López Obrador...

Trotsky, in this period, put forward the concept of bonapartism sui generis (bonapartism of a unique kind). For Trotsky, the Cárdenas government was bonapartist (Cárdenas himself was an army general)), but given the pressure of imperialism he had to balance between the classes and make concessions to the workers.

The concept of bonapartism sui generis continues to be fundamental for understanding some present-day phenomena. We have a number of bourgeois regimes in countries of belated capitalist development that, under certain circumstances, find themselves obliged to make some concessions to the workers, and it is crucial to uphold class independence vis à vis these regimes. There are situations in which a semi-colonial country, including under a bourgeois government, faces an imperialist invasion. Trotsky insisted that revolutionaries take a side. In Mexico City there is a subway station named Etiopía. The symbol of the station is a lion’s head, representing Haile Selassie, who was the emperor of Ethiopia. The reason there is a station with that name is that Cárdenas’ government backed Ethiopia against Mussolini’s invasion in 1935, and also politically supported the emperor. Trotsky insisted on the need to defend Ethiopia, but he did not give any political support to Haile Selassie. This difference is extremely important.

Today, we face this question with the imperialist attacks against Venezuela. It is very important to understand that against this imperialist onslaught, revolutionaries take a side: for the military defense of the besieged South American nation, without giving any political support to the bourgeois bonapartist government of the Chavista president Nicolás Maduro.

Now I will briefly discuss Trotsky’s last battle. This battle too is one he waged when he was in Mexico. It was the fight he carried out against the petty-bourgeois minority in the U.S. Socialist Workers Party (SWP) which – after the Hitler-Stalin Pact was signed, when defending the Soviet Union was quite unpopular – demanded that the party renounce this fundamental class position. Instead, this minority put forward the sham of the “third camp.” The petty-bourgeois faction, led by Max Shachtman and James Burnham, claimed not to side either with imperialism or with the USSR, but with a phantasmagorical “third camp.” In reality, this just disguised the support it wound up giving to imperialism. At the beginning of the anti-Soviet Cold War, the third-campists not only refused to defend Korea against the imperialists that devastated this Asian country, but collaborated with them directly.1 It would be interesting if the partisans of the “theory” of the “third camp” visited North Korea today and saw the remains of the destruction caused by the hundreds of thousands of tons of napalm that the “democratic” imperialists used against it.

So, for Trotsky, was there a solution to the situation of Soviet Union? Yes: he considered it vital to fight for a proletarian political revolution and to extend the revolution internationally. The Stalinist bureaucracy had usurped the political power of the working class, and followed a petty-bourgeois nationalist program diametrically opposed to Marxism. However, the collectivized property forms had not been destroyed, and it was necessary to defend them, while fighting to reestablish proletarian democracy.

Let’s take a step back. It was fundamental to defend a semi-colony like Mexico against imperialism. To fight imperialism, it was necessary to defend the Soviet Union too. Today, you cannot defend Venezuela without also fighting por the defense of Cuba which, at bottom, is the real target of imperialism. Trump has made this very clear. [Applause.]

Trotsky’s last battles, in the darkest part of midnight in the century as was stated in a previous talk, do continue to be very bright stars. They can be our guides in this new midnight in the century that has arrived so early. However, we can – and we must – fight.

The History of Bolivian Trotskyism

By S.

Sándor John

Havana, Cuba, 8 May 2019

Author of Bolivia’s Radical Tradition: Permanent Revolution in the Andes (2009) and El trotskismo boliviano: Revolución permanente en el Altipano (2016); Class Struggle Education Workers activist

Holding this conference in Cuba is enormously important. And in light of the most recent measures, it is crucial to highlight the need to fight in defense of Cuba. Down with the Helms-Burton Act! It necessary to fight for the defense of the Cuban Revolution, and to defeat Trump’s and the Democrats’ attempted coup in Venezuela. This bears a real relation with the perspective of Trotsky, and of Trotsky’s Fourth International, of fighting for a Socialist Federation of the Caribbean and the Socialist United States of Latin America. [Applause]

I also want to say that workers democracy is a fundamental part of genuine Bolshevism, that is, Trotskyism. This involves debate, at times the heated debate, of political differences, because we know that theoretical and programmatic political differences have real consequences in real life. Bolivia is an example of this.

Mural by Bolivian Trotskyist

painter Miguel Alandia Pantoja, “Education and Class

Struggle,” at the Monument of the Revolution, La Paz. (Photo: Sándor John)

Mural by Bolivian Trotskyist

painter Miguel Alandia Pantoja, “Education and Class

Struggle,” at the Monument of the Revolution, La Paz. (Photo: Sándor John)There have been many revolutionary movements in Latin America, but there have been three big Latin American revolutions in the 20th century: the Mexican Revolution, the Bolivian Revolution and the Cuban Revolution. Only one of those, the Cuban, wound up breaking with capitalism. But the Bolivian Revolution of 1952 is connected with another triad: that there have been three countries in the world where Trotskyism acquired a mass influence on a national scale for a significant time. Those three countries were Vietnam, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Bolivia.

How is this to be explained? Is it just some kind of historical curiosity, perhaps a folkloric kind of thing? No, that is not the case. A journalist from the imperialist U.S. magazine, Life, visited Bolivia in 1960, at a time when the Soviet Union was offering to build a tin smelter for Bolivia, since Bolivia had no way to refine its own tin. (For free – by the way, that’s not “imperialism.”)2 When the Soviet delegation arrived at Siglo XX, the most important mine in the country, hundreds of Bolivian miners gave a warm welcome to the Soviet comrades. On their brown helmets, the miners had the symbol of the Fourth International, and the slogans on their banners talked about Lenin and Trotsky.

So what the imperialist journalist told his readers in the U.S., who know nothing of all this, was: you’ve got to understand that the Bolivian miners are all illiterate, and they don’t even know that these mythic guys Lenin and Trotsky are dead, they think they’re still alive. No, that wasn’t what was going on. Instead, it was because for these Bolivian miners, the permanent revolution made sense. Trotskyism made sense for them: it helped their lives and their struggles have meaning; it helped them understand the world they lived in.

In the three countries mentioned previously, there was still no structured Communist Party, and the mass of the working class acquired political consciousness at a time when the Communist International had adopted the policy of the popular front. For the workers of colonial countries like Vietnam (which was a French colony), Ceylon (a British colony) and Bolivia (a neo-colony of the U.S. and to some extent of Britain), the popular front meant supporting their slave-masters. So in those three countries there was an opportunity for Trotskyism, in some form, to become the political expression of the working masses.

In Bolivia there were “democratic prices” for tin during the Second World War. What did that mean? “Democratic prices” for Bolivian tin were low prices, since tin was a strategic material for the imperialist war. The Japanese had captured Malaya, which was a British colony, and tin prices had to kept low, which meant using U.S. machine guns to massacre the miners when they went on strike for higher wages. And the minister of labor who ordered the massacre was from the Stalinist party that had arisen by then, the Partido de la Izquierda Revolucionaria.

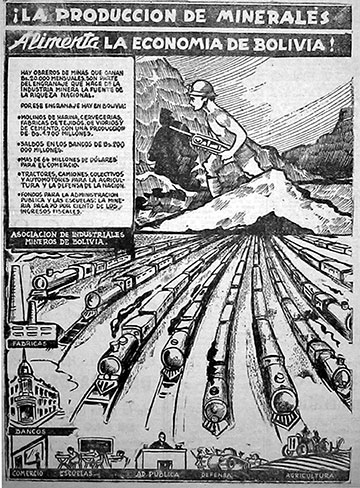

Tin company ad

underlining the importance of mineral production for the

Bolivian economy. To enlarge, click on the image.

Tin company ad

underlining the importance of mineral production for the

Bolivian economy. To enlarge, click on the image.So the theory of permanent revolution was not some exotic thing arriving by chance on the Bolivian Altiplano. The theory and program of permanent revolution held that the proletariat would be the leading force of social revolution in a country of belated capitalist development like Bolivia. And even the advertising materials put out by the “tin barons” in Bolivia reflected this, in their own way, with images like this ad [indicates projected photo to the left] in the bourgeois press, showing tin as the center of the economy. A minority class, the mining proletariat, becomes a giant, generating the greatest part of the hard currency acquired by the country, and has the destiny of the nation in its hands – which was quite true.

But for these miners this meant inhuman, infernal super-exploitation in the mines, in a racist society in which pongueaje continued to exist, that is, obligatory service by the Quechua and Aymara peasants to the gamonales, the owners of the large estates. It was out of this peasantry that there emerged the Bolivian proletariat, maintaining its intimate ties with the peasant villages, particularly when mass layoffs – called “white massacres” in Bolivia – occurred. When they were laid off, as in the case of one of the great heroes of world Trotskyism, César Lora, they went back to the villages and organized peasant unions.

The founders of Bolivian Trotskyism sought, also in their own way, to integrate this reality into their political perspective, as racist oppression of the indigenous majority was a fundamental trait of that society, expressed linguistically, culturally, ethnically and racially against this peasantry. In terms of “uneven and combined development,” this was manifested linguistically: the language of Bolivian mining is a curious mix of words from English (like sink and float, block caving), Spanish (like minero and sindicato, the word for union), together with Quechua and Aymara, like words for certain perforation techniques, and certain jobs (like chasquiri, related to chasqui, the Inca term for messenger).

The Bolivian Trotskyist party, the Partido Obrero Revolucionario (POR–Revolutionary Workers Party), was founded in 1935, with the particularities I have sought to address in the book. A few years later, two of the figures who had participated in its founding visited Trotsky in Mexico. The visit occurred during the Inter-American Indigenist Congress [held in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán in 1940]. The indigenous cultural context and its relation with revolution was also expressed in the art and culture that Bolivian Trotskyists were deeply involved in. You can get an idea of this, for example, in this picture of the “goddess of education” – one particularly relevant to those of us trying to make a living in the education field – in the mural “Education and Class Struggle" – (1957) by the great Bolivian Trotskyist muralist Miguel Alandia Pantoja, who played an important role in the POR and in the foundation of the COB labor federation.

Sándor John speaking on the

history of Bolivian Trotskyism at conference on Leon Trotsky

in Havana, Cuba.

Sándor John speaking on the

history of Bolivian Trotskyism at conference on Leon Trotsky

in Havana, Cuba. (Photo: Gabriel García Higuera)

To the Bolivian miners, the idea that they themselves would be the ones to head up the overthrow of the regime of the tin barons and landowners – the élite known as the “Rosca” – did not seem strange or exotic. The idea that the miners would lead the revolution in Bolivia was a perspective put forward in the famous Thesis of Pulacayo, which was approved (to the surprise of many) by the Miners Federation in 1946. The Pulacayo Thesis was written by the POR, who wanted it to reflect the theory of permanent revolution.

And in fact, it was precisely the Bolivian miners who toppled the government of the Rosca in April 1952. Because the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR–Revolutionary Nationalist Movement) – the bourgeois-nationalist party, which was frequently involved in coup-plotting – scheduled a coup for April 1952 together with the head of the Carabineros (élite police force). But when the army put up much more resistance that the MNR had foreseen, the Carabineros pull out and the MNR leaders say, “all right, let’s make peace with the government.” But the miners literally come down from the mountains surrounding La Paz. With Trotskyists in the front lines, they take the arsenal by assault, seize mortars and other weapons and confront the army, defeating and smashing it in the “April Days” (9-11 April) of 1952.

Trotskyist militants who were part of these events relate that the crowd approached the government palace, the Palacio Quemado; they pound on the door, but no one answers, nobody opens it. They keep on pounding on the door and finally a “soldadito” (soldier), as they say in Bolivia, comes out, scared out of his wits. Trembling with fear, he opens the door; the government has made a run for it. So they all go in, with the miners carrying their leader Juan Lechín on their shoulders, and they tell him: “Juancito, Juancito, you should be president, because we miners, our comrades are the ones who died to overthrow the Rosca.” But Juan Lechín, the Miners Federation leader, who was a member of the MNR at the same time as he flirted with the POR, gets on the phone and calls the “subjefe” (second in command) of the MNR, Hernán Siles Suazo. He says, “come down to the Palace,” and turns government power over to the MNR.

At that point, the only effective armed force was the miners’ militias. In these conditions, control of the situation depended fundamentally on the political leadership, which was in the hands of the MNR. The French imperialist paper Le Monde, whose correspondent was quite intelligent, published a front-page headline on the first anniversary of the revolution in April 1953: “The Bolivian Revolution Between Wall Street and Trotsky.” What happens then, and why are political differences so important? There was enormous political disorientation – there’s a lot to say and I’m running out of time.

But one of the most exciting things about this kind of research is that sometimes someone tells you something that can seem almost mythological, but later you’re digging around in a pile of old documents half-buried in some basement, and you untie some old strings and you find proof that it’s true. In Cochabamba in 1992 I met an old Quechua peasant Trotskyist. We were discussing political differences and then he asked me: “Do you believe the MNR was bourgeois or petty-bourgeois?” The interview per se had ended, and I said, “in my view, bourgeois.” And he started to cry.

I asked him, “comrade, why are you crying?” He said, in the Quechua accent he spoke with: “We had another faction, a third faction, here in Cochabamba, and we said the MNR was bourgeois. Our faction was the only one that defended the Trotskyist theory, stating that it was necessary to defend Bolivia against imperialism, but not politically supporting the government, not even critically. And because of this our faction was broken up and repressed by the bourgeoisie, and the foreign comrades were expelled from the country.”

The MNR reestablished the massacring army, and in 1964 that army carried out the coup under René Barrientos, a name everyone in Cuba knows, since Che Guevara went to Bolivia seeking to overthrow that bloody “gorila” (military dictator).

So political differences have real consequences. Political differences are a question of life and death. And this was shown not once, not two or three times, but countless times in the struggles of the Bolivian Trotskyists. My time has run out, but I want to note that one of things you also really see when studying the history of the Bolivian Trotskyist movement is the heroism, in fact, of the militants of all of the factions.

Summary

During the discussion round, three participants asked Sándor questions. These are his responses.

First, I want to call people’s attention to the events of August 1971, in which there was yet another bloody coup in Bolivia, which brought yet another brutal dictator to power: Hugo Banzer Suárez, who was included in the Hall of Fame of the infamous School of the Americas. The politics of the popular front meant that the workers movement was literally disarmed, both militarily and politically, when the workers and the miners in particular sought, in the most heroic way and against terrible odds, to defeat that coup.

I brought some copies of my book on Bolivian Trotskyism, to donate to libraries. Among other things it discusses the “Quechua-Swiss faction” that arose in Cochabamba in the mid-1950s, which in my opinion had a position that in general terms was more correct than that of the two dominant factions of the POR, regarding the MNR and the bourgeois nationalist government.

To address the questions that were raised:

The Brazilian comrade commented on the view of a writer who stated that the question of the Bolivian Revolution marked the destruction of the Fourth International, and that the Fourth International no longer exists. I agree that the Fourth International does not exist at present. In my opinion, it ceased to exist organizationally in 1951-53, due to the crisis of Pabloism, and the split and dispersion this created. I think it has to be reforged. I don’t agree with the writer you mentioned, nor the current he was part of – led by the British Workers Power group – basically putting an equal sign between both sides, the Pabloists and anti-Pabloists, in the 1953 split.3

The question of Bolivia did not cause the destruction of the Fourth International. Rather, the crisis of the Fourth International was reflected and manifested in the lack of real participation by the other sections in the political life of the Bolivian section, and in the fact that the Pabloist leadership backed the line of political support and adaptation to the MNR. This position was echoed by the SWP leadership, which unfortunately was not thinking much about or questioning this policy.

There was a question about the mita. Mita is the word the Incas used for their obligatory labor system. In Bolivia it became a synonym for a day’s pay. When Che Guevara was in Bolivia, he essentially told the miners that they should leave the mines and go to Ñancahuazú [the guerrilla base camp]. Few of them did that, since they knew that their power resided in being mine workers, whose labor kept the country going. But the miners wanted to show their solidarity, and they voted that they would donate a “mita” for the guerrillas. To punish the miners for this, the dictatorship of René Barrientos carried out the massacre of the Night of San Juan, on the 24th of June 1967, machine-gunning the miners for showing their sympathy and solidarity with the guerrillas who were courageously seeking to fight the U.S.-backed military dictatorship.

Lastly, I’d like to thank the comrade who asked the question about the left wing of the MNR. This is a complex and very important topic which I did not have time to really develop here, but it is key to the argument put forward in the book.

The faction of the POR that carried out “entrism” entered the MNR as such, in other words the MNR as a party. (The faction that did this was the one built by Guillermo Lora, although Lora himself did not go with them.) That party, the MNR, had a left wing, which was headed by Juan Lechín, leader of the Miners Federation and, once the revolution occurs, of the COB labor federation as well. The left wing of the MNR was the mechanism through which this nationalist party and its government controlled the masses.

The POR, its leaders, wrote speeches for Lechín and acted as his advisors for years. When Lechín is made Minister of Labor, the poristas – of both factions – continued writing speeches and documents for him. And enormous illusions were sown in the MNR’s left wing.4

I think this was a really catastrophic and disastrous policy.

Lechín was very popular. He was also one of those who signed

the decree to reestablish the bourgeois army. The MNR left was

the mechanism subjugating the workers movement and the peasant

movement to the bourgeois state.

Comments from the Floor at Havana Trotsky Conference

On Imperialism and on Divisions in the Trotskyist Movement

The following comments were made during the discussion period after a series of presentations on imperialism, the history of the Fourth International and other topics on the first day of the conference (May 6). Given that they were made in Spanish, with only a brief English summary, we provide a full English translation here.

Sándor, May 6:

I have some brief comments, first on the question of imperialism, and secondly on the question of the splits in the Fourth International.

The question of imperialism is of great importance, as U.S. imperialism is seeking to crush the Cuban Revolution, which is a conquest for all of humanity, and is also attacking Venezuela, where – despite the fact that there has not been a social, or socialist, revolution, in the real sense – it is important to defend Venezuela against the onslaught of U.S. imperialism.

The question of the “theory of imperialism” has, in my opinion, enormously important political ramifications. One of the fundamental points in the break between the Second International and the Third International, that is, when Lenin and Trotsky led the founding of the Third International, had to do with radically breaking with the attitude of the Second International, of the social democracy, toward the struggles of the colonial peoples. The Third International said that the revolutions of the oppressed peoples, the colonial revolution, is part of the world socialist revolution. It said that it was necessary to militarily support the struggles of the colonial peoples.

This is of enormous importance. In the Fourth International, as part of the program of permanent revolution, Trotsky fiercely defended this position, including against some who found themselves accidentally in its ranks and who rejected, for example, the defense of Ethiopia against Italy, or who neglected the importance of the national struggles of colonial peoples.

Thus Trotsky and the Fourth International militarily defended China – we’re talking now about bourgeois China, in the 1930s, that is, even before the Chinese Revolution [of 1949] – against imperialist Japan, making the very important distinction between military defense of colonial and semicolonial countries against imperialism and political support to their governments. This distinction is a fundamental one for Trotskyism: defending countries attacked by the imperialists, while this does not necessarily mean giving political support or political confidence to their governments or leadership. This distinction is of great importance. For example: calling for the independence of Puerto Rico, demanding and intransigently standing for the independence of Morocco, including during the Spanish Civil War, when this was also extremely important in terms of turning Franco’s Moroccan troops against him.

The second point has to do with the splits in the Trotskyist movement after the war. This is not just some cloud of data; there is a meaning there. So I think there is a connection with what we heard this morning regarding the annihilation of the Trotskyists in the Soviet Union, in the Vorkuta camp and others, as well as the extermination of many other Trotskyist cadres during the Second World War.

This is one of the elements that set the stage for that crisis. Another is that the Trotskyist movement faced an unforeseen situation: revolutions that were carried out generally by military-bureaucratic means in the case of Eastern Europe, with the formation of bureaucratically deformed workers states, which had to be defended against imperialism without giving political support to their governments, fighting for the proletarian political revolution; and also the revolutions in Yugoslavia and China, Cuba, etc.

So the Fourth International found itself very disoriented. And it split [in 1951-53]. For some who are not intimately familiar with this history, the divisions might seem exotic, esoteric, like the “invisible committee” mentioned previously.5 But in reality, the two standpoints, of the Pabloists and of those who opposed Michel Pablo,6 expressed fundamental differences on the party question: the conscious construction of a revolutionary Marxist leadership based on the working class, to lead socialist revolution on a world scale as the conscious act of millions and millions of proletarians and the oppressed.

There were many excellent revolutionaries among those who found themselves in the ranks of the Pabloists, and the Posadasites,7 but Pabloism suffered from what, in the Trotskyist movement, is called “objectivism,” as if the revolution makes itself, as if the revolution were like an unstoppable tide, which even makes the Stalinist bureaucracy become revolutionary. So this difference, I would argue, was a fundamental divergence on the question of building a Leninist party, the international proletarian, revolutionary party, or tailing after the existing leaderships and forces. This is an enormously important difference.

About What Trotskyism Is and Isn’t

On the second and third days of the conference (May 7 and 8), some speakers put forward positions derived from the so-called “Third Camp socialism” of Max Shachtman and Tony Cliff, who broke from the Fourth International against the position that the Trotskyist movement had always upheld, of unconditional military defense of the USSR against imperialism and capitalist counterrevolution.

Shachtman broke from Trotsky at the outbreak of World War Two, whereas Cliff’s break from the FI occurred during the Korean War, when he refused to side with the Korean and Chinese forces fighting U.S. and British imperialism, branding them as pawns of “Russian imperialism.”

In one of the presentations the argument was made that in the late 1920s in the Soviet Union, Trotsky and the Left Opposition should have united with Nikolai Bukharin, theoretician of the Right Opposition, against Stalin.

Sándor, May 7:

My comments are largely directed to the Cuban compañeras and compañeros present here. I came to Cuba for the first time in 1967 as a child. Like many others, I really liked Coppelia, where they had so many flavors of ice cream.8 Sometimes it might seem as Trotskyism, the Trotskyist movement, is like a lot of different flavors of ice cream. But that is not the case. The debates are about very real issues. For example, the issues we have heard about today, regarding the class nature of the Soviet Union and of other countries where capitalism was destroyed, the question of Bukharin and Trotsky, the question of the orientation of the revolutionary movement – these are questions of life or death for millions and millions of people.

Trotskyism is not just any old thing. Trotskyism was born from the defense to the bitter end of the October Revolution and its conquests. So – should Trotsky and Bukharin have gotten together in the Soviet Union, against the Stalinist center, for “democracy”? Was or was not the main danger the capitalist right – is this a question, for Trotskyists? Under Gorbachev, upholding Bukharin was a trademark of many of those seeking a path toward capitalism in the Soviet Union. This question should be quite clear.

Who was Bukharin? We oppose the show trial and execution of Bukharin, but Bukharin was the theoretician of “socialism in one country”; Bukharin was the theoretician of the political bloc with the Kuomintang, that is, the subordination of the Chinese Communist Party to the national bourgeoisie, which led to the destruction of the Chinese Revolution in 1927. That’s who Bukharin was. So we are talking about real things.

Democracy. Is Trotskyism the champion of democracy “in general”? Does Trotskyism want democracy “in general” in a state where capitalism has been abolished, in a bureaucratically degenerated or deformed workers state? Does Trotskyism call for freedom for all political parties in states of that type? Not according to Trotsky. Not according to Lenin. According to Lenin, if you read his “Theses on Bourgeois Democracy and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat” [1919], you’ll see that democracy “in general” means bourgeois democracy. We stand for proletarian democracy. What is bourgeois democracy, the call for bourgeois democracy, in a bureaucratically degenerated or deformed workers state? It means capitalist counterrevolution. Capitalist counterrevolution.

And this is not an asterisk or a footnote for Trotsky. He wrote many polemics and whole books on these topics. Comrades should know that there was a fundamental split in the Trotskyist movement between those who upheld the program of the Fourth International, of unconditional military defense of the Soviet Union against imperialism, and those who rejected this program, such as Max Shachtman.9 That meant that Shachtman refused to defend the Soviet Union in World War Two.

Where did Shachtman end up? I’ll say it: supporting the Bay of Pigs invasion. And those who upheld the defense of the Soviet Union? Maintaining the unconditional military defense of all the states where capitalism was overthrown, together with the program of the proletarian political revolution.

Democracy has a first and last name, as they say in Mexico. Workers democracy versus bourgeois democracy. There is no democracy “in general.” That is a cover for the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. It can disappear like that, as in Chile, with the illusions in the institutions of the bourgeois state. I was here in Cuba building schools as part of the Julio Antonio Mella Brigade of the Ejército Juvenil del Trabajo while that was happening in Chile.10 If bourgeois democracy is faced with a rightist coup, as in Chile, or the Francoist attack in the Spanish Civil War, for example, we fight to defeat the rightist attack without politically supporting the bourgeois regime. But in a bureaucratically degenerated or deformed workers state, bourgeois democracy is the face of counterrevolution.

Trotsky’s last battle was against diluting or discarding the defense of the first workers state from its enemies. This is not an abstract question but very concrete. It is not different flavors of ice cream. It is a matter of revolution or counterrevolution. Trotskyism was the defender, to the last barricade, of the conquests of the revolution, and that is still the case today. Without that, there is no Trotskyism. [Applause.]

Irina, May 7:

My name is Irina. I’m not an academic. I am very excited to be here in this conference on Leon Trotsky, in Cuba.

I was born and grew up in the Soviet Union in the late 1950s and the ’60s. The first time I heard of Trotsky was from my father. I remember being very excited about the Cuban Revolution, as a Young Pioneer and as a Komsomol [Communist Youth Union] member, and we had special songs about Cuba at the time. My mother, when she learned that I was coming to Cuba now for the first time, reminded me of one of those songs.11

When my father told me about Trotsky, he used to remind me not to talk about it in kindergarten, because even though I was born shortly after Stalin died, people were still afraid to talk about certain things or tell jokes about them in the Soviet Union.

Trotsky’s role as the founder of the Red Army and one of the leaders of the Russian Revolution was not an abstract thing to us, and it was not an abstract thing to my father. My father was 19 years old when he joined the Red Army in 1941, and he fought in the Second World War and lost an eye. My grandfather and my uncle lost legs.

He fought to defend the workers state, the USSR, and along with other people he was captured by the Nazis, twice, and twice he escaped. Within the first hours of the Second World War, my father saw the results of Stalin’s sabotage, as Stalin did not believe that Hitler was going to attack the Soviet Union; and he carried one of his comrades who was mortally wounded.

We also knew and understood Stalin’s dealings when my father’s uncle, my great uncle, who was in the Spanish Civil War in 1936, was thrown in jail by Stalin. After my father went to school after the war, he was often visited by NKVD officers who questioned him because he was captured by the Germans, and Stalin believed that this way people would be brainwashed into enemies.

So, a few things were quite clear for my father and for those like him, and for Trotskyists, like myself. One of them is the class nature of the Soviet Union as a workers state. Another one is who betrayed the USSR: it was Stalin, and not Trotsky, who betrayed the USSR.

And lastly, I want to say that the defense of the workers state of the Cuban Revolution is the task of all the workers of the world. [Applause.]

Irina, May 8:

I have some comments about the characterization of the class nature of the Soviet Union as “state capitalism.”

As a former Soviet citizen, I find these positions ridiculous – and dangerous. Ideas like these serve political purposes and can also only help Stalinism discredit Trotskyism.

The “Third Camp” literally means not to defend the USSR in the war against the Nazis. These theories, that we just heard, mean opposition to the USSR getting the weapons it needed to defend itself.

These positions also mean that Tony Cliff was literally saying that the Korean War was an inter-imperialist war, that it was a war between U.S. imperialism and so-called “Soviet imperialism.” The Soviet Union materially and militarily aiding Cuba was not “Soviet imperialism,” but a crucial part of the struggle against imperialism. [Interjections: Right on!] [Prolonged applause.]

Lastly: the counterrevolutionary destruction of the Soviet Union was a terrible defeat for the entire world’s working class – and nobody can deny this fact today.

- 1. With the support of the State Department, Shachtman helped write anti-Communist propaganda leaflets that U.S. bombers dropped during the war (see the Internationalist Group pamphlet, DSA: Fronting for the Democrats, 2018).

- 2. A reference to our polemics at the conference against the theories of Tony Cliff, Max Shachtman et al. about so-called “Soviet imperialism.”

- 3. That is, the International Secretariat headed by Michel Pablo, Ernest Mandel and Pierre Frank, on the one hand, and the anti-Pabloist International Committee initiated by James P. Cannon’s Socialist Workers Party on the other.

- 4. An example of how this was manifested was the slogan, raised over and over again, of “All Power to the Left” (i.e., Lechín’s MNR Left).

- 5. Ironic reference to one of the presentations which mentioned a French semi-anarchist grouping that refers to itself in this way.

- 6. Michel Pablo (Michalis Raptis, 1911-1996) was the international secretary of the Fourth International after World War Two. The term “Pabloism” refers to his political outlook and that of his political successors (Ernest Mandel and others), characterized by adaptation to the existing leaderships of the workers movement and of the colonial peoples.

- 7. Followers of J. Posadas (Homero Cristalli, 1912-1981), a lieutenant of Pablo who, expressing an extreme version of Pabloism, wound up establishing his own “Posadista Fourth International” in the 1960s.

- 8. Coppelia is the famous state-owned ice-cream emporium in Havana.

- 9. On the last day of the conference, Canadian historian Bryan Palmer, biographer of founding U.S. Trotskyist James P. Cannon and author of Revolutionary Teamsters on the Trotskyist-led Minneapolis strikes of 1934, gave a talk “On Cannon, Shachtman and Early U.S. Trotskyism,” available on line here. Trotsky’s key writings in the 1939-40 struggle against Shachtman and his allies are collected in Trotsky’s crucial book In Defense of Marxism.

- 10. Named after Julio Antonio Mella, a student leader and founder of the Cuban Communist Party, this was a construction brigade of Cuban youth, in which a small number of young volunteers from other countries participated as guests.

- 11. This refers to “Kuba Liubov Maia” (“Cuba, My Love”, 1962), available online here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WzqkZl85qLY