June 2021

“From Black

Nationalism to Maoism to Trotskyism”

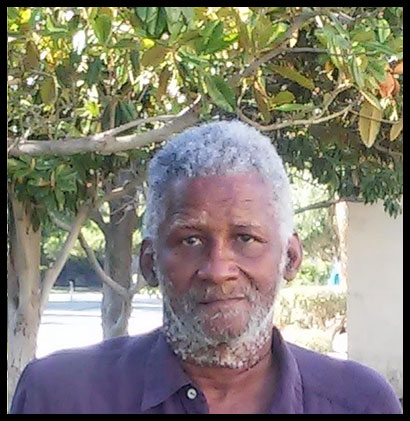

In Memory of Joe Johnson (1948-2021)

Joe Johnson

(1948-2021).

Joe Johnson

(1948-2021). Joseph “Lil Joe” Johnson, whose youthful activism during the rise of the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles was an opening chapter in his life-long dedication to socialism, black freedom and Marxist education, died on June 5 at the age of 73. Born in Louisiana in 1948, he came of age in Los Angeles, where his self-education in the ideas of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky led him to become a mentor to generations of young radicals seeking a road to socialist revolution.

At a commemoration of Joe’s life on June 27, organized by his close comrade Connie White, she described him as a revolutionary “universalist” devoted to freeing all humanity from exploitation and oppression. Unaffiliated since the demise of the Socialist Collective he organized in the early 1970s, in recent years he became a frequent participant in Marxist study groups of the Internationalist Group/Revolutionary Internationalist Youth. With his boundless and contagious enthusiasm for political reading and debate, he combined the forthright, sometimes angular presentation of his views with dedication to political clarification as essential to revolutionary politics.

On 7 August 2020, comrade Johnson gave the following talk, titled “From Black Nationalism to Maoism to Trotskyism,” to the IG/RIY New York study group. It has been edited for publication, with footnotes and subheads added by The Internationalist.

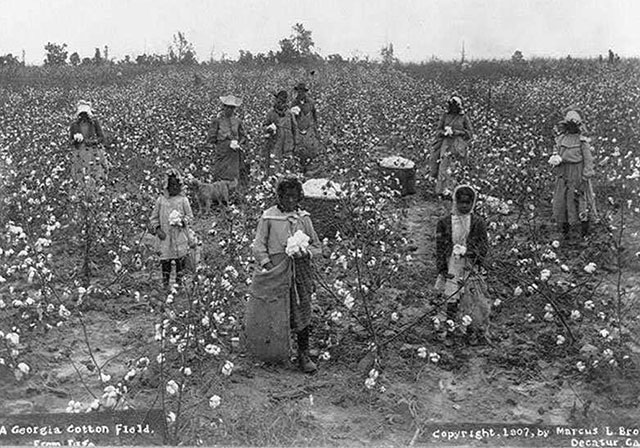

It’s been a long period since we were recruited in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s. If we go further back, the 1920, ’30s, and ’40s were a transitional period from when blacks had been enslaved, and had then become sharecroppers. Racism was the racialization of relations of production; relations of production between the slave owner and the slaves who worked for them. In the movies they show slavery, black people being beaten and oppressed – but they never show them working. They don’t show them in the cotton fields, in the tobacco fields or in the cane fields. You don’t see the actual relations of production that were going on, where a slave owner owns the person and consequently owns whatever the slave produces.

Black Proletarians and Racial Oppression

Sharecroppers in Georgia, 1907. (Photo: PBS)

I asked a comrade to send you all the song “John Henry.”1 In this song, John Henry is a proletarian, but he had been a slave, or maybe his parents were slaves, and subsequently they had become sharecroppers. With the sharecropping system, it wasn’t feudalism like in Europe. The people, once they were freed or emancipated from slavery, they were no longer property, but they had no land, they would work the land of the former slave owners. Now they would exchange the surplus of their produce in order to keep access to the farm that they tilled with their families. Sharecroppers subsequently, a lot of them started leaving, others had just enough money to leave.

The Ku Klux Klan terror was going on in the 1930s and 1940s – like lynching, as you know, the Democrats didn’t really oppose it and Roosevelt didn’t do anything to stop it. For its part, the Communist Party (CP) had taken up the case of the Scottsboro Boys. A lot of blacks had gone to the Second World War, and before that the First, and when they came back were able to get into another class: the proletariat. So in the 1950s, the black people that lived in the urban centers, the proletarian, working-class, wage-laboring, black proletariat concentrated in the cities, was a different reality than when blacks lived as sharecroppers, working in the countryside, in the rural areas.

As I mentioned, the Second World War brought a lot of black people into the proletariat, like my mother, for example. I was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, in the Charity Hospital. My grandmother was a day laborer, she worked at the home of a white person, I don’t know if they were a slave owner or whatever, but she was a cleaner, she was a maid. And my mother was going into the same occupation. My father, was a lumpen who would beat her and all that kind of sexist bullshit. But his father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which came about in the early 1800s as a black church.

The interesting thing is that my grandfather’s father was an abolitionist who married the slave woman that he emancipated during the Civil War. Consequently, his son, who was my grandfather, his name was Horace Greeley Johnson. Horace Greeley! My father didn’t understand the significance of that. His father had a master’s degree, he spoke Latin, he was named after the abolitionist Horace Greeley, who worked with the New York Tribune, which Marx wrote for.

Later on, these connections became important to me, not from the standpoint of learning my history going back to African kings or something like that, but just in terms of the class struggles. What I’m trying to say is that the transition from the rural areas into the urban setting was also the proletarianization of black people who lived in these cities, and that in the 1950s it was the urban black people, the working-class black people, the wage-earning black people who formed unions, participated in unions, and who formed the Civil Rights movement. At the same time, you had the NAACP, which was contesting racial segregation and discrimination in the court system.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott started in 1955. It was same there as in Louisiana: the blacks had to sit in the back of the bus and they had no rights, they couldn’t vote, they were not really citizens: if you can’t vote, what kind of citizenship is that? They wanted citizenship, they wanted to break down the racial barriers, they were definitely not into identity politics.

The other tendency at that time was the black racialists and the black petty bourgeoisie in the Nation of Islam. Originally Malcolm X was the articulate spokesman for this movement which was headed by Elijah Muhammad, its so-called prophet leader.

The Nation of Islam made deals – as before them the Universal Negro Improvement Association of Marcus Garvey (who called himself the “Emperor of the Kingdom of Africa”) made deals with the Ku Klux Klan. They denounced desegregation. They’d talk about the n-word – I’m not using that word. So the black petty bourgeoisie getting their own business was their objective and they said it was only the “house Negro” who wanted to “integrate with the white man.” Black nationalists, as they called themselves, who didn’t confront the state at all; they didn’t challenge a damn thing. They could say I’m black and I’m proud, and criticize the non-violent confrontation tactics of the Civil Rights movement, and make legitimate criticisms of the Democratic Kennedy administration, but they supported segregation and collaborated with the Ku Klux Klan.

The American Nazi Party were invited to a Nation of Islam rally that they attended in their uniforms, where Elijah Muhammad gave a speech; the American Nazi Party praised the Nation of Islam, and the Nation of Islam praised the American Nazi Party. Previously Marcus Garvey had worked with the Ku Klux Klan and praised them as “honest” white folks. At the same time, he attacked the CP, and black Communists specifically, as supposedly wanting to be around the white masters. It sounded militant, but was really reactionary. They didn’t achieve anything.

They lumped all white people together as “the white man.” Like the white cats in the Mississippi Three – the two Jewish men killed by the Klan in Mississippi together with an African American man?2 What white people would black workers work with other than white communists? The Nation of Islam was working for the ruling class by not just keeping black people and white people divided physically but also intellectually and ideologically, so “the white man” was your enemy. That’s what we were taught.

Cold War and Segregation

So this was the situation in which I grew up, in this anti-communist period. The socialization and education in this country was a process of brainwashing Americans about the Communists brainwashing people in Korea; about Khrushchev banging his shoe at the U.N.; the confrontation between U.S. imperialism versus Cuba and the Soviet Union in 1962 that nearly led to nuclear war; the movies they had.

This anti-communism was very deep and was part of our socialization in the 1950s. The schoolchildren, seven-year-old kids would be in a classroom and all of a sudden a buzzer goes off and we had to jump off our chairs and hide under the desks with our backs to the windows, as if that would protect us from a nuclear attack. They promoted the fear of communism, “Russian aggression” – the kind of shit they’re saying today about China3 – and that communists were basically evil. So it wasn’t just the “white man,” including trade-unionists, but the communists were also supposedly devils.

Woman riveter at Lockheed Aircraft in Burbank,

California where Joe Johnson's mother worked during World War

II. (Photo: National Archives)

Woman riveter at Lockheed Aircraft in Burbank,

California where Joe Johnson's mother worked during World War

II. (Photo: National Archives)I grew up in the projects, in inner-city South Central Los Angeles. It wasn’t as impoverished then as it is today. My mother came to L.A. from Louisiana, because black people were recruited by the military to come to California because men in the “white working class,” quote unquote,4 were drafted into the army. Since the military needed weapons and equipment, they brought in blacks, including my mother, who started working at Lockheed Aircraft – she became one of those Rosie the Riveter women. It was a different reality from the South. My father also came from Louisiana. They were living in a hotel in downtown L.A., and at first the only skill she had was domestic work, cleaning houses for people. Later my mother moved into housing projects in Watts; I lived in Nickerson Gardens and Imperial Courts in Watts, Pueblo del Rio. They had “Dogtown”; and in East L.A. it was the White Fence gang’s territory.

At the time, in the black community in South Central L.A., in Watts, Compton – as in Oakland, parts of San Francisco and other places around the country – it was all black people. You would walk down the street, or take a ride, go downtown on the freeway and look right to the left, to the right, and what you saw was black people. There was no integration, it was called de facto segregation. When we thought about white people then, we thought it was like the “Leave It to Beaver” family.5

Racist attack by white sailors on

Chicanos in East L.A., part of the “Zoot Suit Riots,” in 1943.

(Photo: Bettman Archive)

Racist attack by white sailors on

Chicanos in East L.A., part of the “Zoot Suit Riots,” in 1943.

(Photo: Bettman Archive)The ghettoization separated working-class blacks and Chicanos.6 There had been the really brutal conflict of sailors versus the “pachucos” in East L.A. during World War Two. There was no conflict at the time between the black and Chicano people, there were the “zoot-suiters,” who were trying to be cool. Then there was the violence originating with a white racist street gang called the “Spook Hunters.”7 The Chicano gangs, the black gangs were basically organizations of working-class youth in South Central Los Angeles, Watts, East L.A., that were fighting each other, selling drugs, etc. And no one really had any money.

Nationalism in the 1960s

So to be a nationalist back in the 1960s, when I was a teenager dealing with nationalism, there seemed to be a material basis for it, when people said “We want black control over the black community.” We didn't say what “black control of the black community” meant. The Progressive Labor Party then was talking about “community control,” and so were others including the Young Lords Party in Chicago and then New York. It seemed natural that you had these ethnic communities and the consciousness and organizations that we went through. That is because we were working-class and unemployed young people, but consciousness and the organizations weren’t based on our participation in social labor, in social production. What they were then was neighborhood groups.

And like it says in another song I sent out, “Tobacco Road”: “I was born in a dump.... Bring that dynamite and crane, blow it up, start all over again.” So like that song, the idea was saying, OK, we’re going to rebuild the black community and make it as comfortable and decent as possible. Whereas “John Henry” talks about labor as social production. When they were building the railroad, there were workers of every ethnicity, mainly Chinese – they called them “coolies.” And we need each other in the labor process. Class consciousness brings workers together.

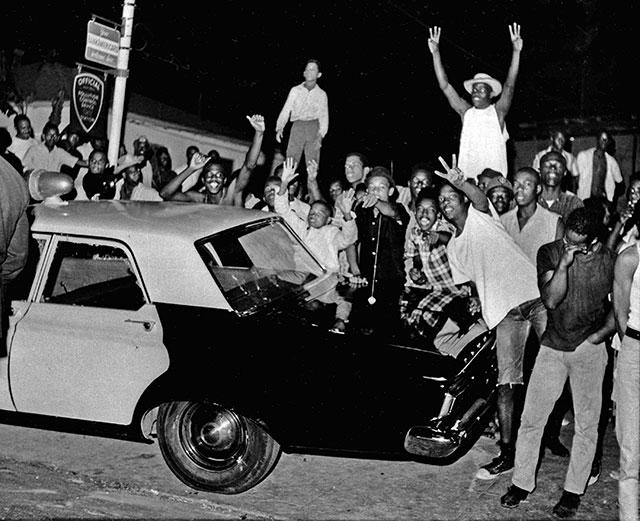

After the Watts Riot, the uprising in 1965, nationalism was put on the agenda as something practicable: people were talking about how we want black police to patrol the neighborhood, the slums, talking about a black mayor. I was out in Compton, and I was thinking, “You know, we could have a black mayor of Compton, someone like [Black Panthers] Elaine Brown or Bunchy Carter, and we could have Huey P. Newton as chief of police in Compton – you get the picture. At the time it seemed rational because it seemed possible.

And I read some stuff about ancient Greece and Rome. I read Plato about the polis [ideal city], independent city-states, and also material about kings in Africa. But what practically can we do with this? Can we make Compton or South Central L.A. an independent republic? Would that mean when you travel from Compton to Long Beach, you have to have a passport? That they would have an army? Would it be like the bantustans in South Africa8 – or like Gaza and the West Bank with the Palestinians, or like Native American reservations? When you begin to think about what it means to talk about black control of the black community, it breaks down.

But after Watts in 1965 and rebellions in other cities, you got black mayors: Tom Bradley in Los Angeles, Harold Washington in Chicago, the black mayor in [Tallahassee] Florida, etc. They were all part of the Democratic Party. A friend of mine used to say Jesse Jackson is not the representative of the black community in the Democratic Party, but a representative of the Democratic Party in the black community. And we said the same thing about the labor lieutenants of capital, the labor officials who are not representatives of the working class in the Democratic Party, but representatives of the Democratic Party inside the trade unions.

That was the substance, the essence, the reality of the black nationalists with black mayors, black chiefs of police. Empiricism: you change the appearance, the color of the skin. Like my comrade Dedon said, “A change in the color of the skin does not change the essence of the state, which is still the state of the capitalist ruling class.” And so you’ve really got to understand political demographics and class realities.

Malcolm spoke to the resentment of black people. We were dealing at that time based on appearances: you see a man beating a man, that is a empirical observation. The man doing the beating is white and the man being beaten is black. That’s an empirical observation. And also the man who is doing the beating has got on a badge, which gives him the authority to beat citizens, to hurt people, to jail people, to kill people. You do not just empirically recognize authority, that takes a deeper understanding of these relationships.

In the ’60s, I spent a lot of time in the California Youth Authority.9 I was doing stuff there that the staff didn’t like and I was thinking of myself at the time as a black nationalist; I didn’t like white people. Then I said I was a Muslim, I stopped eating pork, stopped masturbating, the whole bit. I was doing time; I was 17 years old. They put me in solitary confinement for about 6 months, like with Geronimo.10

They wanted anybody that had any kind of critical thinking separated from the rest of the population and put in solitary confinement. Although I was not really thinking I was a revolutionary, I was thinking at the time as a black nationalist, which is not revolutionary. Black nationalism had the appearance of being revolutionary but in essence it was reactionary. When I got out, I was strictly a nationalist, thought white people were the problem, the whole thing. I considered myself a follower of Malcolm X. Then he was assassinated in 1965.

Malcolm had been arrested and judged. We were the victims of white racism. And it was all white folks as far as we were concerned then. We didn’t at the time look behind the appearances to understand the relationships: the state as special bodies of armed men – but you don’t see “the state”; you see the police, you see the guards, you see the judges, you see white men oppressing black people. You don’t see the basis of the social relations; it’s something you have to learn, through struggle and through analysis and through study.

Maoism and the Panthers

Protesters rise up against police terror in Watts, Los Angeles, August 1965. (Photo: Associated Press)

During the Watts uprising in ’65, for the first time, the police were backing up – they weren’t moving forward killing us.

In the ’50s we’d had gangs – Bunchy Carter, he was with the Slauson gang; my friend Baba and another friend from the Youth Authority, it was the gangs called the 20s and the Outlaws; there was the Gladiators, etc. But all those gangs dissipated after the 1965 rebellion. I didn’t do any looting; I was 17 years old; I didn’t have any analysis, but we were saying: “Hey, rather than a gang to protect our neighborhood from another gang, let’s organize to protect our people from racist attacks and from police brutality.”

And that’s when the Black Panther Party (BPP) came into existence. Bunchy Carter started it here in Los Angeles.11 At that time I was around a fellow who said he was Malcolm X’s cousin; he looked like Malcolm X, with a little hat and a beard. Malcolm said that a revolution overthrows the system, and he talked about armed self-defense. It seemed to jibe with Mao’s Red Book, where Mao was saying political power grows out of the barrel of a gun. So people associated Malcolm X with Mao Zedong.

In one of the films on the Black Panther Party – I’m not talking about the movie about the cartoon character – they present it as opportunistically purchasing Red Books in order to get money to buy guns. I know that the Panther Party did not buy Red Books to sell them to make money off of what they then called “white mother country radicals” – they bought the Red Books to read.

In terms of Maoist groups then: there was one in L.A. led by Michael Laski, called the Communist Party USA (Marxist-Leninist); and the Progressive Labor Party, they were Maoists; there was the Republic of New Afrika. The Panthers were putting [Maoist ideas] together, and we listened to the recordings of Malcolm X’s speeches and we thought, “Yeah!” But Malcolm didn’t really understand revolution as destroying a particular set of social relationships and ushering in different ones in terms of production and distribution of material objects.

We were for the most part very young, in our late teens or twenties – so don’t judge us too harshly. When we first saw Mao’s book On Contradiction, I thought was about people contradicting themselves in an argument. When I first picked up Lenin’s State and Revolution, I thought it was about the state like the state of California. When Mao was talking about the peasant masses, I thought he was talking about farm workers in Los Angeles County, in Long Beach. When Mao talked about the landowner class, I thought he was talking about people who owned apartment buildings. We were interpreting all this material for ourselves with no knowledge of what they actually were and what they meant objectively, materially.

I was running from the police, they were trying to get rid of me in Compton.12 That’s when I started dealing with the Black Panther Party in Los Angeles. I also dealt with the Panthers in Oakland. Masai Hewitt,13 myself and others – we were struggling to understand black nationalism and what it would actually mean to be a “liberated black nation.” The Black Panther Party maintained that the black community was an oppressed nation, but also occupied, that the police were colonial; they called it a “domestic colony.” We watched movies such as The Battle of Algiers, which I encourage people to watch, because it was very important to what we thought it meant to be revolutionaries and the idea of an “armed struggle” for liberation.

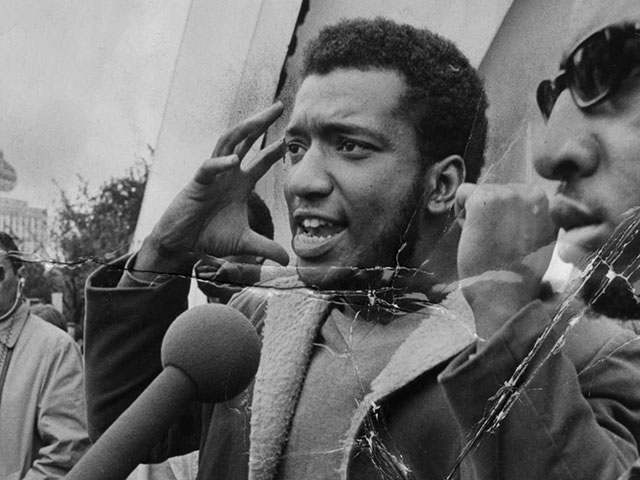

Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton speaking in Chicago’s Grant Park in September 1969. Three months later he was murdered by Chicago police working with the FBI in infamous COINTELPRO operation. (Photo: Chicago Tribune)

The Panther Party, as you know: it was suppressed. We all know about George Jackson, killed in San Quentin. You know about Fred Hampton being assassinated together with Mark Clark. We know about Mumia Abu-Jamal, and how the black Democratic mayor of Philadelphia, Wilson Goode, dropped bombs on the MOVE house.14 They started calling the house a bunker. When you hear the media talking about a person’s home as a bunker, you know the bombs are going to drop soon.

The Black Panther Party down on Central Avenue was raided in ’69; I had been dealing with them for maybe a year or so, but I was in East L.A. doing other stuff.15 The reason that the Panther Party on Central Avenue survived, that they came out alive, was because we were able to bring out the community and bring out the press. Geronimo, he was in the building, along with others – Roland Freeman, “Peaches” [Renee Moore], different people. They survived the shoot-out, but a factor in this was that the media was there and consequently a tank wasn’t brought in like in Waco, Texas,16 or aerial bombardment like in the case of MOVE. So the struggle was real.

“In Love with Theory”

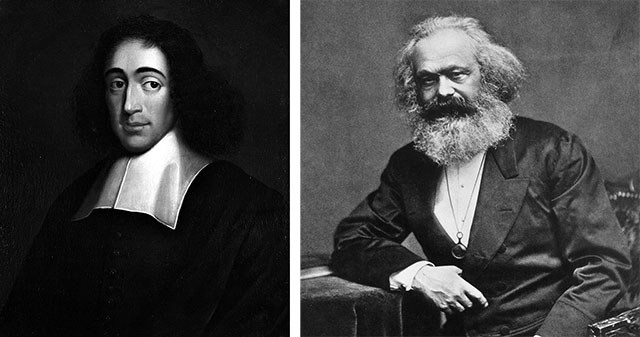

Baruch Spinoza and Karl Marx

In the intervening period, I had the good fortune that I was always in love with theory. I had already read Plato’s Dialogues, but I also got a lot of help from Spinoza’s Theological-Political Treatise – he analyzed the scriptures and materialism – as well as Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason, as I was trying to figure out what was going on. That’s when I read the Communist Manifesto and it was, “Wow.” Everything became clear. And it’s still clear.

I didn’t have a phone then, so I ran to the telephone booth and got the directory, to get me the phone number for the Communist Party, because the pamphlet was called the Manifesto of the Communist Party. I said, “Hey, I want to be a part of this”; but on the phone they were hemming and hawing and kind of suspicious. But in this group with [Hakim] Jamal and the Malcolm X Foundation,17 I was talking about the Communist Manifesto and Lenin’s State and Revolution. I had an idea of what revolution is and that black nationalism wasn't revolutionary.

So, I came to understand that it’s not about individuals getting rich and improving the conditions of black people in the inner city, it’s about the necessity for what Lenin called the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat. From reading the Communist Manifesto and State and Revolution, I was hooked, I was convinced.

In 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated and we had the uprisings all over the country, about 120 cities in flames. The music was encouraging too, Bob Dylan, the beginnings of rock and roll anti-war culture, which was developing together with the black liberation movement. I was about 19 years old then, I was not even old enough to see my man John Coltrane, since you had to be 21 to go see him.

In terms of reading, at that point I hadn’t read anything from the SWP.18 Just Mao’s Red Book and stuff from the CP. But reading Marx and Lenin made a big difference: I was able to transition away from racialism, what they called nationalism – though I really didn’t understand class struggle and class consciousness until the 1970s. But I want to emphasize that people wanted to be revolutionaries; we wanted to be revolutionaries, but didn’t know how.

There was a Maoist bookstore in Watts. There was the Communist Party bookstore, Mike Davis was working there at the time.19 The CP bookstore had a lot of good Marxist literature from Progress Publishers, and Laski and his group had Peking Review and some Maoist works, posters and little badges everyone would wear.

The SWP had their bookstore in East L.A. Me and my comrades from Compton would go there and they would direct us to their black literature section, where they would give us books by Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Richard Wright and others; nothing wrong with those books. W.E.B. Du Bois’ Souls of Black Folks. But we were not introduced to Trotskyist literature! So we didn’t have a coherent political analysis. We didn’t even know what to analyze, though black nationalism was bankrupt.

Around that time, the students at Carver Junior High School got beat up by the police,20 and I had been driven out of Compton by the police. So I was out in Los Angeles in the underground working with a group called the Black Students Alliance when there was a city-wide student strike protest. Responding to what we saw occur, I repeatedly came into conflict with the Communist Party, because they were always working with the Democratic Party and attempting to water down what we were trying to do. I didn’t understand it in class politics/party terms; I thought of it then as what the Maoists called “Khrushchev revisionism.” I didn’t understand it yet as Stalinism.

“Trotsky Was What the Doctor Ordered”

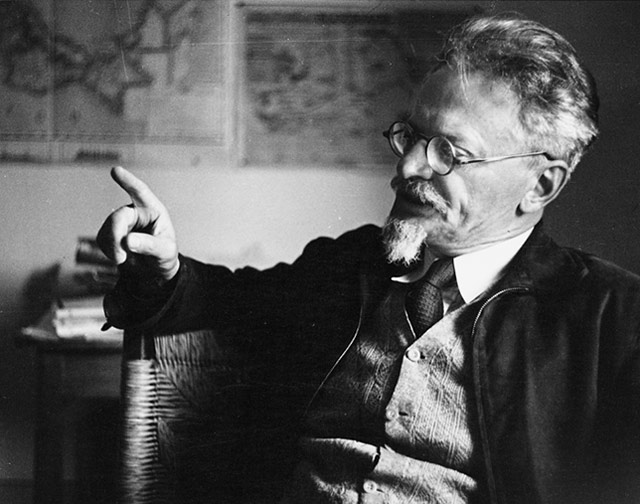

Leon Trotsky in Coyoacán, Mexico, 1939. (Photo: © A.H. Buchman)

A few years later, I happened to go to a conference against the killing of the students at Kent State.21 I saw a poster there saying, “Rebuild the Fourth International.” I knew about Marx and the First International; I knew from Lenin about Karl Kautsky and the Second International; I didn't know what became of the Third International, but the idea of a new International sounded wonderful to me. I wanted to investigate, what the hell is a Fourth International?

It turned out the poster was for a conference organized by the Workers League, so I had some discussions with Tim Wohlforth.22 He had an analysis of black nationalism from a Trotskyist working-class perspective, and they had a list of books that I was able to hunt down on my own. I took about six months or so out in order to get this Trotskyism thing, reading The Revolution Betrayed, which was difficult because I wasn’t familiar with any of the categories about the Soviet Union in the 1920s and ’30s. I read In Defense of Marxism, which I loved, particularly the part called “The ABC of Materialist Dialectics.”

That was because I had already been interested in philosophy, with Mao’s “On Contradiction” plus Plato, Spinoza – and I really wanted to learn something new philosophically, so I really loved that item by Trotsky; not only that, but it was useful! Now I was able to understand and do combat with the Communist Party! I was able to understand the labor bureaucracy, I was able to understand the connections between the CP and the Soviet Union. Trotsky at that time for me was what the doctor ordered, and I needed that.

Later on, the 1980s brought the repressive era of the Reagan administration [starting with] the breaking of the PATCO strike; then the 1990s, beginning with Bill Clinton’s attacks on the singer/rapper Sister Soulja.23 Clinton did this at a rally organized by Jesse Jackson, who had been a Civil Rights worker in Chicago in the 1960s, but in the ’80s ran for president. Jackson was a Democrat, as were most of the former Civil Rights leaders who had participated in struggles with the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], Martin Luther King, the NAACP; then the so-called Black Congressional Caucus which is nothing but black Democrats, so-called “progressives.”

All of this stuff back in the 1980s was different from the experiences we had in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s when we were actually confronting the state power and the racialized institutions that existed – segregation, Jim Crow, discrimination in jobs and hiring, against not only blacks but also women. You can look back at the protests in Birmingham, Alabama, where the state teargassed and turned water hoses on black children protesters.

So like Marx said in his “Theses on Feuerbach,” theory is a practical thing, it’s not just sitting around and interpreting phenomena; it’s revolutionary. To understand the world and change it requires theoretical investigation and depth of knowledge. What Marx does is like The Wizard of Oz, exposing what is behind the curtain. You hear the wizard’s voice, you see the smoke, but you don’t understand that it’s a show, that there are things going on behind the curtain that you don’t have access to. Almost like the tradition of the ancient Israelites, who carried the “Ark of the Covenant” [supposedly containing the Ten Commandments] behind a curtain; while in ancient Egypt, the priests would carry representations of the gods, but only they had access to the inner sanctum.

So theory, Marxism, enabled me to take a peek behind the

curtain. And I’m still peeking behind the curtain.

* * *

Some of comrade Johnson’s comments responding to the question/discussion period:

I just want to point something out, about identity politics, for young people that grew up, say, in the ’90s and thereafter: the motives of identity politics are not the same as the black nationalism of the latter part of the 1960s.

Connie and I were talking about the DSA, Freedom Socialist Party, some group that calls itself Marx21. And there are people talking about “white skin privilege.” The identity people are not the same as the Black Panther Party back in the ’60s and ’70s. Now you’ve got these opportunists on TV, you know the type. They have programs with a black person explaining to the camera how black people feel about police killings, with Al Sharpton and with Cornel West talk about the “black prophetic tradition.” And there are people who get paid to be experts on what it means to be a Negro; they get paid to push identity politics and denounce the working class as a bunch of racist SOBs.

The media in this country don’t tell viewers what’s going on in the world; they tell them what they’re supposed to think about what’s going on in the world. They encourage the bombing and destruction, coups in Latin America, etc. Meanwhile AOC talks about Venezuela.24 You know, these people represent the Democratic Party, and that’s what this identity politics stuff is all about. And as part of it, when working-class people go to the university, white students coming from the working class are made to feel guilt.

So the identity politics people are not the same people as the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, etc.; they don't have the same interests, they are not of the same class. So much for identity politics…

The movement in the 1960s and ’70s, we had to deal with concrete problems because we were very serious about revolution. We read Lenin, we read Marx. We saw what was going on in Vietnam, with the burning of villages, the picture of the little girl running after being burned with napalm.

We understood that this state will do anything to maintain their power. And with the murder of Fred Hampton and George Jackson, some of us were coming toward an understanding of class struggle. Masai Hewitt and John Huggins and others of us dealt with these questions, and I was basically assigned to work with the Black Students Alliance.

So I was free to do a critical analysis. [Eventually] we found our way to Trotskyism. We had no help. The CP certainly didn’t help us.

In 1969, I had a falling out with the Black Panther Party, when I was giving a speech at their “United Front Against Fascism” conference in Oakland.25 The Spartacist League and the Progressive Labor Party and other Marxist groups were there. But the Spartacist League was being physically attacked for doing a critical analysis of the Communist Party. And I said, “Don’t do that, don’t attack these people.” And I diverted from where my speech was, there in Bobby Hutton Park, and addressed the conflict.

Recall that the Panthers and others who talked about Maoism in the black community did not discuss Mao’s “bloc of four classes” or what a popular front was. To refer to Maoism initially meant political power brought “from the barrel of a gun”; and later on, “serve the people.”

During the civil war in China, Mao’s Chinese Community Party and People’s Liberation Army, based on the peasantry, set up “liberated zones” in which they would organize production, distribution, medical aid, etc. That’s what they meant by serving the people, in the context of guerilla warfare.

Whereas the concept of actually “having power” in black communities was not actually dealt with by the Panther Party or other groups. “Serve the people” meant sickle-cell anemia testing, breakfast for children – all this is good, wonderful stuff. But it ain’t revolutionary. I put it this way around the time of the United Front Against Fascism, it could sound cynical, but what they were calling “socialism by example” became a black militant version of the Salvation Army.

How could the working class come to power? How will we win state power? These were revolutionary concepts that were not dealt with by any of the organizations that I was familiar with in the ’60s. Eventually we did read Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution, in particular the chapter called “Five Days,” where he talks about how the military ranks were won over to the revolution. What a soviet means; and state power, how you confront and overcome it. But back in the ’60s this wasn’t really discussed, we weren’t really aware of it.

What about the situation today? “Black Lives Matter” is a complaint, about police killing black people; and you hear people talking about “Defund the Police.” The state won’t defund itself! We didn’t have ignorant statements like that, “Defund the police.” And, “Speak truth to power”: what the hell does that mean? There’s nothing revolutionary about speaking truth to power. Revolution is for the working class to become the power! Proletarian revolution would abolish capitalist commodity production and wage labor; it would replace markets and circulation of commodities with “from each according to his abilities, to each according to their needs.”

I wanted to mention that in 1919, two years after the founding of the Soviet state, while there was civil war in Russia; Rosa Luxemburg and the Spartakusbund in Germany; troops from France also in mutiny – while the working class was rising up against capital and struggling for power throughout Europe, in America you had the “race riots” against blacks in 1919. They had revolutions, we had race riots.

In his book Black Bourgeoisie (1957), E. Franklin Frazier talked about how racial divisions were used. And blacks were brought into the military. You need to attack racism, but that doesn’t mean black people should be applauding or proud of the fact – like identity politics people – that black soldiers were sent to kill workers in Europe or Japan, or that the Tuskegee airmen were used to drop bombs across the goddamn world.26

So again, identity politics is bourgeois.

In the late ’60s they started talking about black capitalism. And Fred Hampton said, when there was discussion of black and white, and class struggle: We do not fight fire with fire; the best way to fight fire is with water. We do not fight racism with black cultural nationalism; we fight racism with interracial working-class solidarity. We do not fight capitalism by promoting black capitalism; we fight capitalism by producing socialism.27

But in this sense, he was talking about the social programs of the Black Panther Party. Myself and others in the movement at that time, we still weren’t referring to the expropriation of the expropriators and the forces of production; a planned economy – these kinds of discussions were kept from us by the CP and others. And I was in jail at the time. I’ll leave it there. ■

Remembering Lil Joe

At the memorial meeting “Lil Joe Johnson, Celebrating a Revolutionary Life,” 27 June 2021.

(Photo: Dat Dang / Facebook)

The following remarks were made by Los Angeles transit worker Joe Wagner, a supporter of the Internationalist Group, at the June 27 commemoration for Joe Johnson.

¡Luchar por el socialismo! ¡Que viva Lil Joe!

I first met Lil Joe at a Marxist study group, almost 20 years ago. The office we would meet at was up a massive fright of stairs. It was work to make it up those stairs, but he was happy to do it. He knew that at the end of the struggle to make it up 77 steps (I counted them), he would be in a room with youth and others that were interested in every word and every carefully crafted sentence that he would formulate.

He was a natural debater. A worldly man who made complex ideas accessible. He loved getting to know the youth and learning as he was teaching complex ideas. Marxism, he would explain in intricate detail, is not a dogma but a guide to action; theory is never to be denigrated. He encouraged the youth to read what he had read. He would say that one’s experience with oppression is not enough to develop a plan to overcome it.

At a recent talk, Lil Joe gave on the lessons of his political development, “From Black Nationalism to Maoism to Trotskyism,” he explained to the youth of today that revolutionary politics did not just come to him, like a premonition, but it was a process of hard struggle and hard theoretical study and debate.

He knew that the ruling class would never, ever allow the exploited and oppressed to be taught in their institutions what it would take to overthrow their rule. So he saw it as his job to seek out the knowledge he needed, to educate himself and then to raise the level of political consciousness of the oppressed. Not just the consciousness that they were exploited as workers or oppressed as an oppressed community but a far deeper level of understanding. The objective that Lil Joe had was to prepare the young worker for the coming to power of the proletariat; the consciousness that the workers should rule and bring all the oppressed up with them.

To his last days, he was reading and studying and analyzing his previously held positions. He was steeled but remained flexible to challenging even his own preconceived notions in the course of debates and happily learning new things.

And all the knowledge that he learned, that he understood, that helped point out the road forward to revolution, he wanted to share it with others, so that the youth of today could likewise get closer to finding the road to revolution. That’s what made him light up with joy: knowing that in Marxist theory he could see a light at the end of the tunnel for humanity and that he had a key role to play in passing on important lessons to the youth of today, who could, armed with that knowledge, better continue forward on that road to liberation.

We must carry forward this fight: let’s continue reading, studying, debating and putting what we learn into action, to follow the revolutionary road to victory. Long live Lil Joe! ■

- 1. A popular rendition of the song by Harry Belafonte is online at youtube.com/watch?v=ydTRk1l0ZqI.

- 2. On 21 June 1964, “Freedom Summer” activists James Chaney (21), Andrew Goodman (20) and Michael Schwerner (24) were arrested by police, then “disappeared” and brutally murdered by the KKK in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

- 3. Comrade Johnson’s views on the “Russian Question” and China had changed sharply from the period when his Socialist Collective merged briefly with the “third-campist” International Socialists in 1974.

- 4. This is a polemical reference to present-day leftists who claim there is a separate “white working class”; comrade Johnson had circulated among friends and colleagues our article “The Myth of a ‘White Working Class’ – ‘Identity Politics’ at a Dead End,” The Internationalist No. 46, January-February 2017.

- 5. “Leave It to Beaver” (1957-63) was a TV sitcom purveying an image of white middle-class Cold War “normality.”

- 6. See the article by Charles Brover, “‘American Apartheid’ By Design,” on the website of Class Struggle Education Workers, which reproduces the federal government housing map of Los Angeles showing in red the areas to which black, Latino and Asian populations were largely confined, hence the term “red-lining.”

- 7. Mexican American youth who wore a style of clothing known as the “zoot suit” were sometimes known as “pachucos,” and were the targets of racist attacks spearheaded by white sailors in Los Angeles’ so-called “Zoot Suit Riots” of June 1943. (This is the topic of the 1981 film based on Chicano playwright Luis Valdez’s play Zoot Suit.) Originating in the 1940s, the white racist gang that comrade Johnson refers to sought to violently enforce racial boundaries against African Americans newly arrived in L.A.

- 8. Bantustans were the supposed black “homelands” that apartheid South Africa set up as reserves of black labor and a means of police-state control.

- 9. The California Youth Authority was the notoriously brutal incarceration system for “youth offenders” in California, renamed Division of Juvenile Justice in 2005.

- 10. Los Angeles Black Panther leader Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt (1947-2011) spent 8 years in solitary confinement during the 27 years he was imprisoned on frame-up murder charges as part of the FBI/police COINTELPRO program; in 1997 his conviction was overturned. (See “Geronimo Is Out! Now Free Mumia!,” The Internationalist supplement, June 1997).

- 11. Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter (1942-1969), together with fellow L.A. Panther leader John Huggins (1945-1969), was shot dead on the UCLA campus by members of Ron Karenga’s “cultural nationalist” US (United Slaves) organization in a COINTELPRO-instigated assassination.

- 12. A letter to the Socialist Workers Party’s Militant (2 August 1968) describes the arrest of Joseph Johnson and two others by Compton police who found them with leaflets by a local “Black Nationalist Party” as well as “some books by Lenin”; it quotes Johnson as attributing the felony charges of assaulting a police officer to “the cops ‘remembering Watts.’”

- 13. Raymond “Masai” Hewitt (1941-1988) was a leading Black Panther in Los Angeles and a target of a notorious COINTELPRO smear campaign.

- 14. George Jackson (1941-1971), one of the “Soledad Brothers,” became an influential voice of black radicalism before prison authorities murdered him while he was trying to escape San Quentin prison on 21 August 1971. Targeted by COINTELPRO, Chicago Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton (1948-1969) and Mark Clark (1947-1969) were assassinated by police in a COINTELPRO operation on 4 December 1969. On 13 May 1985, with the approval of Mayor Goode, Philadelphia police dropped an explosive incendiary provided by Regan’s “Justice” Department on the MOVE commune, killing 11 black men, women and children. For more on the MOVE massacre, see “It Will Take Workers’ Power to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal!” The Internationalist No. 26, July 2007.

- 15. Four days after the police murder of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago, the L.A. Black Panther office on 41st and Central was targeted by the world’s first major raid by a SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) team. Cops demolished the office, wounded 6 Panthers and arrested 13 in the 8 December 1969 raid.

- 16. Early in the Democratic administration of Bill Clinton, in a siege culminating on 19 April 1993, the FBI, ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms) and other federal and state agencies used tanks and other weaponry against the “Branch Davidians” compound in Waco, allegedly in search of illegal firearms, killing 76 members of the religious sect, including 20 children.

- 17. The Malcolm X Foundation was established by Hakim Jamal (1931-1973), an activist then based in Compton, around 1968.

- 18. Though it had turned decisively to reformism in the early 1960s, the Socialist Workers Party was still the largest organization claiming the heritage of Trotskyism at that time.

- 19. Former CPer Mike Davis is a prolific leftist writer and historian; most recently he co-authored Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (2020).

- 20. Los Angeles-area high schools and junior highs were rocked by a wave of student walkouts in 1967-69, the best known of which are the 1968 “East L.A. walkouts” or “Chicano blowouts” depicted in the 2006 film Walkout. Carver Junior High was one of the schools where protests involved large numbers of young black (and some white) students. In 1969, Joe Johnson was one of the speakers who made the rounds of schools in solidarity with these protests.

- 21. On 4 May 1970, the Ohio National Guard opened fire on a protest at Kent State University against Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, killing 4 students and wounding 9.

- 22. The Workers League (WL), led by Tim Wohlforth (1933-2019), was the U.S. affiliate of Gerry Healy’s “International Committee of the Fourth International.” Lil Joe became a member of the WL, whose Bulletin (15 March 1971) published his analysis of the Panthers’ split between followers of Huey Newton (1942-1989) and Eldridge Cleaver (1935-1998). Joe broke with the Healy/Wohlforth brand of “Trotskyism” over several issues including their support for the 1971 New York police “strike.”

- 23. In 1981, Ronald Reagan kicked off his first presidential term by firing more than 11,000 striking members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO), escalating the anti-union offensive of his Democratic predecessor, Jimmy Carter. Campaigning for the presidency in 1992, Bill Clinton gave a speech to Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition in which he infamously compared Sister Souljah to the notorious Klansman David Duke.

- 24. Democratic Socialists of America congressperson Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez chimed in with the rest of the Democratic caucus backing U.S. “democracy” promotion in Venezuela, voting $20 million for the failed coup attempt of 2019.

- 25. As repression against the Panthers continued to escalate, in July 1969 they held a “United Front Against Fascism” conference in Oakland, a bloc with the CP, Peace and Freedom parties in a largely unsuccessful effort to cement an ongoing alliance with reformist left and liberal forces.

- 26. The U.S. sent approximately 200,000 black troops, in segregated units, to Europe during World War One; during WWII, 1.2 million African Americans were in the armed forces; the first black flying squadron, known as the “Tuskegee airmen,” was deployed to North Africa, and then to Italy.

- 27. A video of the famous 1969 Fred Hampton speech referred to is online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jnlYA00Ffwo