September 2021

Celebrating International Women’s Day

Forum on “Women, Class Struggle and Revolution”

The Uprising by Diego Rivera, 1931.

On March 10, the CUNY Internationalist Clubs held an online forum titled “Women, Class Struggle and Revolution” in honor of International Women’s Day. U.S. capitalism’s triple pandemic of COVID-19, economic crisis and racist police murder has thrown the triple oppression of black, Latina and immigrant workers into sharp relief. Meanwhile, pandemic profiteers gouged enormous profits1 from the exploitation of “essential” workers, many of whom paid the price with their lives.

At a laundromat on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, immigrant women workers undertook an inspiring and difficult struggle against horrible working conditions and abuse by management, including wage theft, and on two occasions, industrial fires. Despite reprisals by the company, Wash Supply, the women formed their own union. Publicly launching their campaign with the Laundry Workers Center on 25 November 2020, the compañeras delivered a letter of demands to the management of the company, among which was recognition of the union they were in the process of forming. Rallying and marching with them were defenders of labor and immigrant rights, including the CUNY Internationalist Clubs and Revolutionary Internationalist Youth (RIY).

Employing tactics from the classic union-busting playbook, the bosses waged a counter-campaign to silence and intimidate the women – but failed. Last January, less than a week before the scheduled unionization vote, they fired Yuriana, one of the workers active in protesting unsafe and abusive conditions. Her supposed infraction was not meeting the new hourly quota of 100 pounds of washed and folded laundry. This brought new protests, in which we and other activists joined in rallying to their defense outside the laundromat.

Less than a month later, the bosses fired all the workers and closed the laundromat in the wake of a victorious vote for unionization. Protests escalated. On February 27 and March 6, activists from many unions were among the hundreds that rallied outside another laundromat owned by Liox Cleaners, Wash Supply’s parent company, in solidarity with the courageous fired workers. These protests were held on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where in 1909, thousands of young, mainly immigrant women garment workers went on strike in what became known as the Uprising of the 20,000, which was key to the rise of International Women’s Day. After rallying in front of Liox, we marched both times to the site of the former Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, where in 1911, 146 immigrant garment workers died in a factory fire.

A featured speaker at our March 10 International Women’s Day forum was Jacqueline, one of the fired Wash Supply workers. (See below.) Her remarks are followed by presentations, edited for publication, by comrades Kaitlan and Noor of the Revolutionary Internationalist Youth.

Wash

Supply Worker: “We Face

Mistreatment and Discrimination”

Compañeras from Wash Supply laundromat before they delivered their demands to management, 25 November 2020. (Internationalist Photo)

Wash Supply worker Jacqueline’s remarks to the International Women’s Day forum were made in the form of answers to questions and are translated here.

Could you start by telling us a little about yourself?

Jacqueline: I am from Mexico, from the state of Guerrero. What led me to come to the United States is the same thing that leads a lot of people here that come from Mexico. I came here to seek a better life and to have a better way of supporting my family. In Mexico, it has become very difficult to do so. Although people come here being told about the American dream, when they arrive, they find that it is very difficult to get by, particularly if one doesn’t speak English. If one doesn’t have papers, we face mistreatment, discrimination and not being afforded the same rights.

Could you tell us a bit about what life is like for you as an immigrant worker in the United States?

Jacqueline: It means getting up very early, often at 4 a.m. Going into work, I would wash various loads of clothes, take them to the dryer, and then fold. Without having eaten before work, we would often have to wait until noon to have breakfast. Even then, we would be rushing and at times running to have time to eat. Sometimes we would not even be able to wash our hands before eating because we did not get a break. We could not even get ready to eat before having to return and start working again.

When did you start working at Wash Supply and what was it like to work there?

Jacqueline: I worked at Wash Supply for a year and a half before it got shut down. Before the pandemic, things were calmer since there was less pressure. With the pandemic, things at work got a lot worse. They would make us stand up while we were eating lunch and they increased the amount and speed of work we had. If we did not go along with these new requirements, they threatened to get rid of us and replace us with other workers.

NYC’s Union Square, February 20: The day they were fired, Wash Supply workers came out to rally in solidarity with Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama fighting to form a union.(Internationalist Photo)

Mahoma (organizer with the Laundry Workers Center): Something that I also want to add is an example of what a day working at Wash Supply was like for the workers. In the winter, there was no heat. In the summer, no ventilation. Especially in this current pandemic where places are required to be well ventilated. In addition to that, they have to handle clothes that have human fluids like urine, feces, or vomit. It’s very bad. This isn’t only at Wash Supply; the whole industry has the same conditions.

Could you tell us about the work conditions, payment, and treatment from the management?

At site of the 1911

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, Wash Supply workers

receive painting by Internationalist Club member of Clara

Lemlich, a leader of the 1909 “Uprising of the 20,000.”

At site of the 1911

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, Wash Supply workers

receive painting by Internationalist Club member of Clara

Lemlich, a leader of the 1909 “Uprising of the 20,000.”Jacqueline: In terms of the pay, it was very low. I was paid ten dollars an hour. In terms of management, they treated all of us very badly. Sometimes when we would try to talk to them, they would not respond at all and when they did, they would respond in annoyance. The manager always pressured us and was constantly after us.

Could you tell us about the fires?

Jacqueline: I was there on two occasions when fires occurred. The first of the two fires was the worst of them. We were working and suddenly a fire broke out in one of the dryers. The managers didn’t tell us to stop working or take any measures against the fire. We were told to go into the manager’s office and huddle in there amidst all of the toxic smoke. Then, we were told to step out for a bit and come back in while there was still smoke present. We had to clean up and go back to folding the laundry while breathing in all of the smoke which irritated our eyes and throats.

Could you tell us about the fire extinguisher and exit at Wash Supply? It is my understanding that management did not know how to use the fire extinguisher.

Jacqueline: Yes, exactly. They did not know where the fire extinguisher was and when someone found it, the manager did not know how to use it. One of the workers took the risk of opening the dryer where the fire had started and attempted to put it out. The flames were growing stronger and we all started yelling and shouting that we needed to get out of there immediately. To get out of the place was even more difficult because the manager had always kept the exit closed. The emergency exit door was always sealed shut.

Why did you and the other workers from Wash Supply decide to start the campaign to form a union?

One of the fired Wash

Supply workers speaks at International Women’s Day rally of

hundreds outside laundry’s parent company, Liox, March 6.

One of the fired Wash

Supply workers speaks at International Women’s Day rally of

hundreds outside laundry’s parent company, Liox, March 6.(Internationalist Photo)

Jacqueline: In order to have our rights respected and to be treated better.

Is it true that management was also committing wage theft along with paying the workers below the New York state minimum wage and not paying overtime rates?

Jacqueline: Yes, it was wage theft. They paid us below the legal minimum wage of New York ($15/hr) and often made us work 10 to 12 hours without ever paying us time and a half.

What would you like us, as students and people who stand in solidarity with your struggle, to know?

Jacqueline: Above all, that you give us your support in order to bring justice to what we are demanding and justice to all of our compañeras.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Jacqueline: Regarding the protests, I want to give a big thank you to all who have supported us and have come out to back us up and show solidarity. I would like people to continue to hear us out and listen to our voices. We want the whole community to hear our voices and the voices of all the compañeras. ■

Black Women Face Capitalism’s Triple Pandemic

Residents of Harlem wait

in line for food and masks, April 2020. (Photo: Bebeto Matthews)

Residents of Harlem wait

in line for food and masks, April 2020. (Photo: Bebeto Matthews)By Kaitlan

We all remember the immense wave of protests that swept the country last summer in response to the murder of George Floyd. As they developed, those protests weren’t solely about the vicious lynching of George Floyd, but came to be about all those who were murdered at the hands of the police – a list of names I could spend the next two hours reading and wouldn’t get through. Black women are among those killed by the police as well, but their cases are rarely covered by the media and often, much of what we do know is largely due their families sharing the information and their own researchers gathering the information.

Two names which have become widely known are those of Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor. Breonna’s murder sparked mass outrage, which continued when only one of the officers was charged (not for killing Breonna, but for endangering her neighbors). The endless list also includes Eleanor Bumpurs, Mya Hall (a black transgender woman), Aiyana Stanley-Jones, who was only 7 years old when she was killed, and many more.

Last summer’s protests connected the issue of racist killings by police to the everyday brutalization and violence that black people are forced to deal with under American capitalism. Black people face disproportionate levels of poverty and, within the past year, a disproportionate level of coronavirus infections that comes as a direct result of structural racial oppression. We learned from very early on in the pandemic that black and Latino people are twice as likely to die from COVID, and three times as likely to be hospitalized as a result of the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As of now, black people account for 14.9% of deaths where the person’s race is known, while representing 12.4% of the population. That means that at this point, 1 in 555 black Americans has died of COVID.2

This is due to many reasons, like overcrowded housing (which makes “isolating” when you have COVID virtually impossible) and the fact that black people hold many of the “frontline” jobs that come in direct contact with the public – like public transit, grocery and retail work, and maintenance. On top of this, the medical system often reflects concepts and assumptions stemming from long-standing racist ideology that imply there are biological differences between white and black people and that black people have “thicker skin,” a higher pain tolerance, etc. This creates pretty deadly circumstances, particularly for women. Women frequently aren’t taken seriously when they see a doctor about pain management, but black women have an even harder time because of such racist concepts, assumptions about their condition, etc.

What is the most deadly medical situation for black women? Childbirth. Pregnancy-related deaths occur for black women at three to four times the rate of white women. Black women are less likely to develop breast cancer but 40% more likely to die from it.3 The situation is critical. As of now, little is known about how the pandemic has affected black women medically, but I’m sure we’ll hear more about that soon.

As we’ve been discussing tonight, women workers are doubly oppressed in this society. Black women workers are triply oppressed under capitalism and it should come as no surprise that this pandemic has been crushing for black women. In most parts of the country, schools have been closed since March 2020. In New York, some schools have opened but it’s been very disorganized and chaotic. School closures have been burdensome for women, among other reasons because the weight of making sure their kids grasp the material is primarily put on them. And if it’s crushing for the population at large then, again, it is even more so for black, Latina and immigrant women.

Mothers who are also workers need to find – in the midst of a pandemic – someone to watch their children, as the children who are usually at school are now at home, and most black and Latina workers have jobs that don’t allow for them to “work from home.” Of course, this is if they still have a job. Black women are more likely than others to consider stepping away from their careers due to the pandemic and the issues it has created for them.4 Black people in general are twice as likely as whites to have lost their jobs, but black, Hispanic and Asian women accounted for almost all jobs lost by women in December 2020. Over the past year, 2.3 million women have left the labor force, but the unemployment statistics do not include these women. So, while the official unemployment rate for black women was 8.9% in February 2021 and 8.5 % for Latinas (still disproportionately high), the actual rate was 14.1% for black women and 13.1% for Latinas.5

So, if women are working, they’re also dealing with finding childcare and supporting their children, who have suffered tremendously during the pandemic. Meanwhile, they try their hardest not to bring COVID home, which is hard in the small, overcrowded apartments that are classic in NYC. They’re also grieving over friends and loved ones who have died. If women are not working, it’s essentially just endless home drudgery (cooking and cleaning) and worrying about where the next meal is going to come from. And black and Latina women, employed or not, face having to figure out how they and their family members can survive under U.S. capitalism’s never-ending police terror.

So what do we do?

It’s very clear that racial oppression is systemic and structural. It is ingrained in, intrinsic to and irremovable from capitalism. American capitalism cannot function or operate without it. Racism is an ideological expression of that structural double oppression of black people, and a manifestation of the immense social inequality that comes as a result of capitalism. So when we talk about structural racial oppression, we are talking about something that is embedded into the economic and social system that we live in today. When we factor in class society’s oppression of women, in which the nuclear family is key, we get what Marxists refer to as the triple oppression of black and Latina working women.

We’re talking about the United States, where capitalism was built on genocide against indigenous people and black chattel slavery, whose legacy continued under Jim Crow. With that understanding, while we fight it every day, racial oppression cannot be abolished within this system. What do I mean by that? Racism and racist oppression cannot be eradicated through the simple shifting of a couple billion dollars around, or changing the name of this street, or replacing the white CEO of this company with a black one. This all implies that there is a way to make capitalism “just” and favorable to all – but there isn’t. Exploitation is the whole basis of the capitalist system.

Many liberals and reformists want to pretend that fundamental change can be brought about in a way that is either an internal change within oneself or within the system. But revolutionaries are honest in saying that what’s needed to uproot racial oppression is socialist revolution. Structural racial oppression comes from the need of capitalism to keep a certain sector of the working class subdued and at the bottom of society, so that the capitalists can pay them poverty wages, throw them out of work and bring them back when needed (as part of the “reserve army of labor”), treat their labor and their lives as if they’re expendable, while fostering divisions within the working class.

In a similar way, as a comrade mentioned in the discussion, the oppression of women is not something that can be eradicated within the existing framework of capitalist society, as it is from the needs and structures of class society that the oppression of women arose historically and continues today. With this material oppression of women comes its ideological reflections, like sexism or male chauvinism, that among other things serve to “explain” and justify it. All of this is part of why the triple oppression of black, Latina and immigrant working-class women has brought deadly consequences in what we have called U.S. capitalism’s triple pandemic of racist terror, COVID-19 and economic crisis.

Can we fight the oppression of women or the oppression of black people by calling on the rulers to establish “justice”? No, in the words of Rosa Luxemburg, we do not depend on or believe in the “justice” of the ruling class. There is no justice under capitalism. We cannot rely on, or put illusions in the Democrats, who in this country are perceived by many as the more “progressive” political party, nor can we put illusions in the Republicans, Greens, or any capitalist party.

Instead, we must rely on the politically independent, revolutionary power of the working class. The potential of that power has been shown on a small scale with the different workers mobilizations that have happened around the country, like the strike of the workers at the huge Hunts Point market in the Bronx, the unionization campaign at Amazon in Bessemer, Alabama (in which black women are playing a leading role), at Wash Supply and elsewhere. Such struggles need to be broadened, strengthened and developed into mass mobilizations of workers all around the country. That requires a revolutionary leadership.

We want women’s liberation, we want black liberation! That is only possible through a socialist revolution waged by the multiracial, multiethnic working class, that will liberate all exploited and oppressed people, as part of the fight for a socialist world. ■

Bangladesh, Mexico, NYC:

Women Workers In Struggle

Garment workers on

strike in Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh, 2013. (Photo: Andrew Biraj /

Reuters)

Garment workers on

strike in Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh, 2013. (Photo: Andrew Biraj /

Reuters) By Noor

We’ve heard a first-hand account of how a courageous group of Mexican immigrant women are giving voice to the struggle against the intolerable conditions, wage theft and abuse faced by thousands who work in laundry sweatshops across New York City. This industry is run on the labor of immigrants – mostly women – who are superexploited and lack many of the protections nominally afforded all workers. They have no job security, are paid well below the minimum wage and are forced to work under dreadful conditions.

Jacqueline, one of the women workers fired from Wash Supply for organizing a union, painted a grim picture of what life is like inside the sweatshop. The workers are treated as replaceable because, for the bosses, workers are nothing more than raw material to be exploited. These workers experienced two instances in which a fire broke out with fire exits blocked and no extinguisher in sight. This is eerily similar to the conditions that resulted in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire of 1911, where 146 immigrant garment workers (123 women and girls and 23 men) died in a fire at a garment factory in New York City’s Greenwich Village. The Triangle Shirtwaist fire wasn’t a singular incident, by any means. Workers dying as a result of negligent bosses is a trend in the textile industry – it’s a norm.

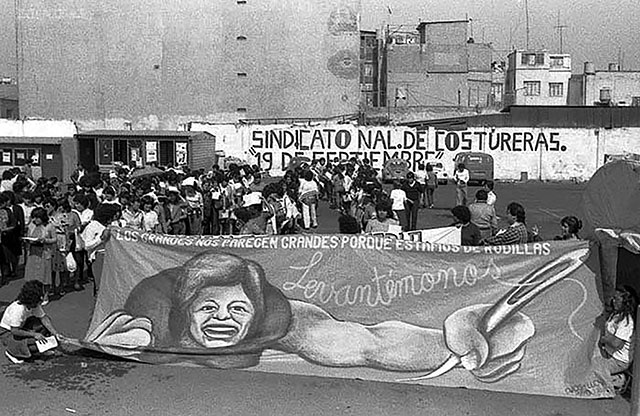

Garment workers of the Sindicato Nacional de Costureras 19 de Septiembre. The union’s name commemorates date of 1985 Mexico City earthquake. Banner says oppressors “seem huge to us because we are on our knees. Let us rise.” (Photo: Frida Hartz)

For example, in Bangladesh, where my family is from, textile workers (most of whom are women) work long hours in unsafe, unregulated sweatshops as breadwinners for their families, earning a meager $64 a month on average.6 In 2013, over 1,000 workers died in the collapse of Rana Plaza, a building housing garment factories near the capital, Dhaka, while about 2,500 were left injured. Many were trapped under the rubble. The building wasn’t properly constructed and had too much heavy equipment for the structure to withstand.

In Mexico City, 1,600 women garment workers (costureras) died in their workshops in the terrible earthquake of 19 September 1985. Many were buried alive. In the aftermath, the bosses literally had the machines dug out but left the women workers to die.7Those who survived organized a union, the Sindicato Nacional de Costureras 19 de Septiembre.

I bring these examples up to make clear that the struggle of women workers is an international one. The similarity of conditions faced by these workers, as well as the callous disregard for their lives by the bosses, is clear. They are brutally exploited and vulnerable to losing their jobs and their lives. International Women’s Day came out of the struggles and strikes by immigrant working women on the Lower East Side of New York City, in conjunction with working-class men as a means of pressing for their demands through class struggle.

The struggle that these women of the Wash Supply union are bravely engaging in is a continuation of that tradition, started by immigrant textile workers in 1909, right here in New York City.

It was clear then and it’s clear now that the bosses care more about their machines than the workers. It’s essential to learn from past struggles and to connect them up with the present. This is one aspect of internationalism – connecting the struggle of the worldwide working class, helping to mobilize and lead it in socialist revolution.

So of course, it goes beyond just one laundromat; the workers movement must help blaze a trail to organize the unorganized, from the workers at Amazon to small shops like Wash Supply to sweatshops in Bangladesh and Mexico, where starvation wages and deadly working conditions prevail. There’s a chant we frequently use at protests – it’s one of my favorites. It goes, “Asian, Latin, Black, and White – Workers of the World Unite!” ■

- 1. For example, the top 13 retailers in the U.S. saw profits rise by an average of 40%.

- 2. APM Research Lab, “The Color of Coronavirus: COVID-19 Deaths By Race and Ethnicity in the U.S” (5 March 2021).

- 3. “Patterns and Trends in Age-Specific Black-White Difference in Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality – United States, 1999-2014,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (14 October 2016).

- 4. “For Black Working Women, COVID-19 Has Been a Heavy Burden,” Wall Street Journal (30 September 2020).

- 5. “Unemployment rate understates what’s going on, expert says, as millions of women remain out of workforce,” CNBC (5 March 2021); “Why Black Women In the US Are Being Hit Hardest by Coronavirus,” Business Because (7 August 2020).

- 6. “The dark side of fast fashion,” UPF Webzine, 17 April 2018.

- 7. See “Mexican Women Workers – Class Struggle in the Global Sweatshop,” Women and Revolution No. 34, Spring 1988.