Showdown on West Coast Docks: The Battle of Longview

(November 2011).

click on photo for article

Chicago Plant Occupation Electrifies Labor

(December 2008).

click on photo for article

May Day Strike Against the War Shuts Down

U.S. West Coast Ports

(May 2008)

click on photo for article

June 2017

L.A. “Sanctuary Clinic”

Defends Immigrant Patients

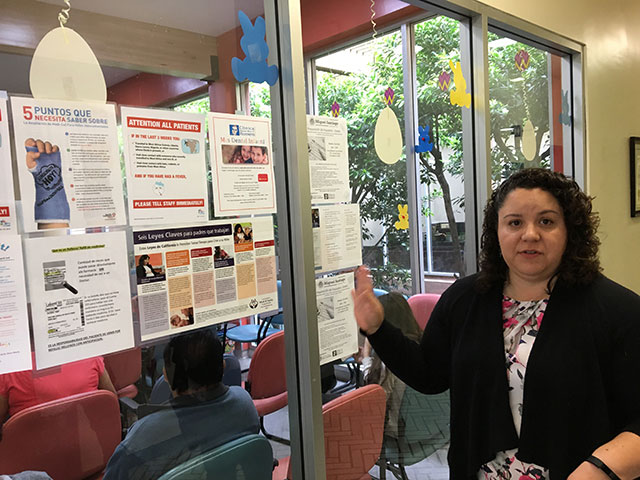

Ana Grande, organizing director for the Clínica Oscar A. Romero in Los Angeles. (CSEW photo)

The following article is reprinted from the Class Struggle Education Workers website, http://edworkersunite.blogspot.com/.

Bringing the power of labor into the fight to defeat the anti-immigrant onslaught has been central to the Class Struggle Education Workers’ work in the past period. This is reflected in materials on the CSEW site, such as “NYC Schools Must Be a Sanctuary for Immigrant and All Students – Keep I.C.E. Cops Out of Our Schools,” “NYC Health Care Workers Say: Mobilize the Power of Labor to Defend Muslims and Immigrants,” and “The Crime of Medical Deportations.” CSEW members have played a leading role in putting into practice the call to establish committees to defend immigrants in unions, schools and workplaces, while helping build protests and mobilizations against attacks and provocations aimed at immigrants, Muslims and basic democratic rights.

So it was with great interest that CSEW activists learned that a health clinic in Los Angeles had declared itself a sanctuary from the recent wave of raids targeting undocumented immigrants (“L.A. Health Clinic Protects Immigrants Against Illness — and Deportation,” LA Weekly, 15 March). Located in the largely Central American Pico-Union neighborhood, the clinic is named after Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador, who was assassinated in 1980 by right-wing death squads determined to silence his denunciations of U.S.-backed army terror during the Salvadoran civil war. The LA Weekly reported:

“Administrators for the Clínica Monseñor Oscar A. Romero declared the sanctuary policy ... after caregivers reported an alarming rise in the number of missed medical appointments since the Immigrant and Customs Enforcement sweeps began in earnest in the area in mid-February. Most of the patients who come to clinic for care were born in El Salvador, Guatemala or Mexico, and an estimated 40 percent of them are undocumented, according to Ana Grande, the organizing director for the clinic.”

Grande was quoted as stating, “If agents come in storming, our providers are prepared to act as human shields.”

Inspired by this courageous stance, we sent her the motion passed by NYC health care workers Local 768 (part of AFSCME DC 37) on the fight to “defend undocumented immigrants in need of health care from round-ups, jail and deportation.” Phone discussions on the importance of linking up these struggles from coast to coast led to a mid-April visit to the Clínica Romero, where CSEW member Sándor John interviewed Ana Grande. The edited and abridged interview is published below.

* * *

Can you tell us a little about the clinic, its name, and the patient population?

Clínica Monseñor Oscar Romero was founded in 1983 by a group of Salvadoran refugees and their allies. It was originally a concept from a committee of the El Rescate legal services group, who were [concerned about] health access for the new diaspora of Central Americans in Los Angeles. There were some nurses in the community who said, “Let’s start a clinic.” It started as a non-profit, volunteer-run free clinic. The founders wanted to ensure that there would be a community organizing department within the clinic, so we’d be able to tackle what we now know as the “social determinants of health” such as housing, immigration, food scarcity, mental health issues, you name it.

Over the last 34 years we have transitioned to having a staff of 183, and we’re now a federally qualified agency with 12,000 patients. 95% of our patients are monolingual Spanish-speaking, and 2% speak a Mayan language called Kanjobal spoken in Guatemala, and others speak dialects of Náhuatl. There are now some African immigrants as well. We believe that we owe it to our immigrant patients, and our brothers and sisters in the community at large, to be working in their defense, advocating for them.

So the clinic was founded at the height of the civil war in El Salvador.

Yes. The clinic is named Monseñor Oscar Romero partly because he lived and worked at a hospital in El Salvador, El Hospitalito, which we provide resources for, but also because we always wanted to be a voice for the voiceless. Over 40% of our patients are undocumented, and those that are legal residents or citizens come from mixed-status families. I was a patient here when I was a kid; I used to get my shots here. I came in two years ago as community organizing director, and I get to work directly with the culture I’m from. My father is the cousin of Rutilio Grande, who was Monseñor Romero’s best friend and the first religious martyr of the civil war. One of the reasons why Monseñor Romero became the “voice of the voiceless” was to highlight the human rights atrocities in El Salvador.

In the mid-1980s, a large number of people from the Salvadoran diaspora moved to this part of Los Angeles, as well as Hondurans and Guatemalans. At that time, we had what we called sanctuaries, which were churches that became a network of solidarity and a community of support for one another. I started being trained as an organizer at that time, and now we’re taking up that concept with what we’re living through right now.

The thing is, we’ve always been living through mass deportations, even in the Obama era. Everyone was like, “Oh, it’s not going to be horrible, because it’s Obama, he’s not going to go into clinics or schools.” Well, yes and no. But nobody did anything, other than the “Dreamers,” who were really at the forefront of being undocumented and unafraid. Now when Trump came into power, there was now a major scare; it was going to up the ante, and we knew that no place was going to be safe. So now we see raids happening not only at workplaces, which they always have, but we see them more in neighborhoods, everywhere, during daylight time.

Because we’ve been very vocal about our undocumented population, we felt it would behoove us to have policies in place that not only protected the organization, but those within it, and of course our patients. We talk about being a part of the sanctuary network or the “safe space” network now. We’re not providing sanctuary in the sense that it used to have; we’re not housing people here. We’re now part of a more extensive network...

Your point about deportations under Obama is a very important one, which we’ve raised in articles like the one about medical deportations. A lot of the institutional and policy structures that Trump is ramping up go back to that. The LA Weekly article said that if I.C.E. came storming in, clinic personnel would be human shields.

Yes, because they would be breaking the law, because this is private property. We are hoping to continue with that message, but obviously that is not the route we would like to go...

At the City University of New York, the campus presidents have made various declarations with an escape hatch, where they say if I.C.E. comes with a legal order, they will comply. We’ve been calling on people to say, “No, we won’t comply,” and if they raid a campus or go to the home or workplace of a student or campus worker, and threaten them or their family with deportation, we would shut down the campus and spread that to the rest of the University. We’ve also talked about comparisons to the fight against the Fugitive Slave Act in the period before the U.S. Civil War.

Well, as Monseñor Romero would say, “No man is obliged to abide by the law that is contrary to the laws of God.”

One of the things that the CSEW emphasizes is that we think the labor movement – and more broadly the working class, which has such a key immigrant component – has the power to actually shut down these raids. [The Clínica Romero’s staff is unionized in the SEIU.] I wanted to end the interview by asking if you have any message for health workers in the New York area, or the students and faculty that are organizing around these issues.

I think right now we are living in a time where the best of us is being called forth. So how are we going to be humane with the rest of humanity that is being tackled, marginalized, oppressed? And it is up to us to really be at that forefront, and to not give up. Giving up is not a choice right now. It is really our responsibility to change the course of history. We’re proud of the position we’ve taken. Becoming a “safe clinic,” or a “sanctuary clinic,” has allowed our patients to feel safer, and our staff to become more united. When you are in solidarity, that is what happens. ■