January 2014

Break with the

Tripartite Alliance Popular Front –

Build a Revolutionary Workers Party!

South Africa: Workers Slam

ANC Neo-Apartheid Regime

Striking auto service workers, members of NUMSA, in Johannesburg, September 2013. (Photo: Alexander Joe/AFP)

The August 2012 massacre of mine workers at Marikana marked a turning point in South African history, intensifying class struggle and opening what could become a revolutionary period. If the Sharpeville massacre of 1960 drove home the murderous nature of the apartheid regime of white supremacy, Marikana laid bare the deadly reality of its successor, the neo-apartheid regime presided over by the African National Congress (ANC), which is still based on the super-exploitation of black labor. Sharpeville, with its toll of 69 black protesters killed and more than 18,000 activists arrested in the aftermath, produced an outpouring of mass disobedience of the notorious passbook laws, as well as the banning of the ANC and the start of armed resistance.

We are now witnessing the political fallout of the point-blank police slaughter of 34 strikers at the Marikana mine, and the reverberations will be felt around the world. Its role as guarantor of racist capitalism exposed, the ANC’s governing alliance is beginning to come undone in the face of massive discontent among the vast black and non-white majority over the continued poverty, police brutality and exclusion. As South African workers direct their anger at their black capitalist rulers, the key to the outcome will be to forge a revolutionary workers party to fight for international socialist revolution – a fight that starts now, not some time in the distant future. Otherwise, as always in the past, it will be the capitalist slave masters who will profit.

From December 17 to 20, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) held a special congress which officially declared its break with the ANC, and with the Tripartite Alliance – which also includes the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP).1 The Metalworkers condemned the police massacre at Marikana, while the SACP and COSATU leaders defended the police and the government. Since then the Metalworkers union has been the object of a vilification campaign by the ANC, SACP and COSATU. At the congress, NUMSA secretary general Irvin Jim declared that the union was “gatvol” (fed up) with the attacks on it and would no longer support ANC candidates.

NUMSA’s break came shortly after the death of ANC leader and South African president Nelson Mandela, and the special congress was postponed in view of the official mourning period. For over a week, millions came out to view the casket, participate in mass assemblies and line the streets for the funeral procession in order to pay their respects to the man seen as the symbol of the fight against apartheid. But current ANC president Jacob Zuma was roundly booed and jeered by the thousands-strong crowd at the December 10 memorial meeting in Johannesburg’s soccer stadium. Many turned thumbs down and called for Zuma to resign over pervasive corruption while the masses continue to suffer poverty, unemployment and inequality.

Barely a week later, the 1,200 delegates at the NUMSA congress voted to break with the ANC in no uncertain terms. The Declaration issued by the congress states that:

“… the leadership of the ANC and SACP is protecting the interests of white monopoly capital and imperialism against the interests of the working class. The ANC and SACP leadership defends the ownership and control of the mines, banks and monopoly industries in the hands of white monopoly capital and imperialism….

“That is why our comrades died as they did at Marikana and de Doorns [where police shot down striking farm workers in January 2013]. It was not incompetence on the part of the police. It was the conscious, deliberate support, by the armed forces of the state, for the interests of shareholders and against the interests of workers….

“The ANC has been captured by the representatives of an enemy class. It has adopted the strategic plan of that class. Its leadership has shown that it will not let the small issue of democracy get in the way of defending its control. As well as the continued poverty of the majority of the working class, the result of this has been the slaughter of workers.

“It is clear from this picture that the working class cannot any longer see the ANC or the SACP as its class allies in any meaningful sense.”

The Declaration noted that “for more than 20 years we have been urging our members to swell the ranks of the ANC and SACP,” but that “our existing strategy was becoming outdated. Swelling the ranks has merely resulted in delivering more working class victims, like lambs to the slaughter by the ANC’s bourgeois leadership.” Consequently, the Congress “calls on COSATU to break from the alliance,” and stated that “NUMSA as an organization will neither endorse nor support the ANC or any other political party in 2014.”

NUMSA’s break with the Tripartite Alliance promises to be an earthquake in South African politics, and could even cost the ANC its so-far overwhelming electoral majority. With over 330,000 members, NUMSA is not only the largest trade union on the African continent, it has also been looked to by hundreds of thousands of members of other unions as the main leader of working-class resistance to the increasingly right-wing policies of the ANC government. But more than that, the break puts the need for a genuinely revolutionary workers party front and center. The NUMSA Declaration itself notes:

“The South African Communist Party (SACP) leadership has become embedded in the state and is failing to act as the vanguard of the working class. The chance of winning it back onto the path of working class struggle for working class power is very remote…. For the struggle for socialism, the working class needs a political organisation committed in theory and practice to socialism.”

The Declaration continues:

“Numsa will explore the establishment of a Movement for Socialism as the working class needs a political organization committed in its policies and actions to the establishment of a socialist South Africa. Numsa will conduct a thoroughgoing discussion on previous attempts to build socialism.”

The question is, what is meant by “socialism,” and how do you get there? While the leaders of the National Union of Metalworkers, and many others in South Africa, accuse the SACP of abandoning the struggle for socialism and instead administering capitalism, they have not broken with the Stalinist/Menshevik program that long before Marikana laid the basis for this betrayal.2 When speaking of “socialism,” many are calling for different policies within the framework of the present South African capitalist state rather than socialist revolution to bring down that state. Yet no matter who is sitting in government, capitalism in South Africa is inherently racist and can only be based on the grinding poverty of the black toilers.

What “Post-Apartheid” South Africa?

South African police pose with guns drawn over their victims. Then the ANC authorities charged the victims with murder under a law from the apartheid regime. (Photo: Alon Skuy/The Times of Johannesburg)

The African National Congress has been in power for 20 years now, an entire generation, yet for all the talk of a “post-apartheid” South Africa, the country is as unequal as ever – or more so. And much as they despise the racist rulers of the past, many poor and working people are gatvol with ANC. This has led to an eruption of popular unrest over the last decade – over evictions, police brutality, cutoffs and price hikes of electricity, transport costs, unemployment – as South Africa has become the “protest capital of the world.” But with NUMSA’s break, this dispersed “rebellion of the poor” could gain powerful working-class organization and leadership – and that spectre has South Africa’s rulers, white and black, worried.

The 1994 elections marked the end of formal apartheid with its rigid segregation, exclusion and denial of basic rights, including voting, to the vast black majority (three-quarters of all South Africans), as well as discrimination against the coloured3 and Asian populations. But the elaborate legal superstructure was devised to secure a regime of white supremacy based on the superexploitation of black labor which existed long before the institution of formal apartheid in 1948, and which survives essentially intact today. In fact, unemployment has increased sharply in recent years, reaching 35% of the workforce; real wages of workers have fallen, and the degree of economic inequality is notably greater today than it was in 1994.4

Sure, there are some black managers and even a few CEOs drawn from the ANC (Tokyo Sexwale, Cyril Ramaphosa), the Group Areas Act is gone, and Nelson Mandela moved into the wealthy suburb of Houghton Estate. Yes, there has been some improvement in supplying water, electricity and access to education (which is not free) for the mass of the population, although the provision of basic services is outrageously deficient. But the masses of black South Africans still live in impoverished townships, shantytowns have spread, and the police still move in like an occupying military force to put down unrest. The massacre at Marikana was only different in scope, as protesters in Khyelitsha, Grahamstown or Kennedy Road, Durban can confirm.

The same “Randlords,” the owners of the mining conglomerates

and banks who formed the core of the South African ruling

class under apartheid, run the show today. And this is also

part of Nelson Mandela’s legacy. On his release from prison,

he spoke of “a fundamental restructuring of our political and

economic systems to address the inequalities of apartheid” and

nationalizing the mines. But shortly after, as South African

economist Sampie Terreblanche explained in his book, Lost

in Transformation (2012), Mandela started having secret

meetings with Harry Oppenheimer, the retired head of the

Anglo-American Corporation and De Beers Consolidated Mines,

and in the end the ANC leader agreed not to tamper with South

African capitalism.

Mass revulsion over Marikana massacre didn’t stop South African police from doing it again, shooting on and killing striking farm workers at De Doorn, in Western Cape province, 9 January 2013. (Photo: Reuters)

Another key factor was the collapse of the Soviet Union, as a result of which, according to SACP leader Ronnie Kasrils, “doubt had come to reign supreme: we believed, wrongly, there was no other option” (Guardian [London], 23 June 2013). Kasrils, the head of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (the Spear of the Nation), went on:

“From 1991 to 1996 the battle for the ANC’s soul got under way, and was eventually lost to corporate power: we were entrapped by the neoliberal economy – or, as some today cry out, we ‘sold our people down the river’.”

Western-trained ANC economists began meeting with the mine bosses at the Development Bank of South Africa and, prodded by veiled threats from the U.S. government of Bill Clinton, on the eve of the 1994 elections, Kasrils says, the SACP and ANC made its “Faustian bargain,” “we took an IMF loan … with strings attached that precluded a radical economic agenda.”

There followed a series of economic programs – the Reconstruction and Development Plan (RDP) under Mandela, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) program under his successor Thabo Mbeki, and now the National Development Plan (NDP) under Zuma – all of which continued to fill the coffers of the white capitalists while superexploiting their black “wage slaves,” paying them even less than the bare minimum needed to live and raise a family. State-owned companies were privatized, financial markets deregulated, tariffs lowered allowing massive imports and consequent de-industrialization, exchange controls eliminated allowing a massive outflow of profits, etc. – all of which were agreed to by the ANC and the SACP.

In fact, the amount of money spent on social grants to poor South Africans pales in comparison to the hundreds of billions of rand in government funds pumped into companies in order to promote Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). The result has been the creation of a narrow layer of BEE tycoons, who have often led attacks on black workers. Cyril Ramaphosa, the former head of the National Union of Mineworkers and quintessence of BEE capitalists, sits on the board of Lonmin. As such on 15 August 2012 he demanded action against platinum strikers at Marikana engaged in “dastardly criminal” conduct. The next day, the police committed the heinous crime. Four months later, the ANC elected Ramaphosa as its deputy president!

So how does the South African Communist Party justify this promotion of black capitalists and the pro-business agenda of the ANC government in which several SACP leaders sit while party members staff every ministry including the police? It’s all in the service of the “National Democratic Revolution,” which “unites … a range of classes and social strata” and in which “the working class builds its hegemony in every site of power” (The South African Road to Socialism [2012]). From the outset, the SACP’s participation in the ANC has been based on the Stalinist dogma of a “two-stage” revolution, in which the first stage is supposedly bourgeois-democratic, or anti-imperialist, or anti-feudal, etc., but definitely not socialist.

In fact, the first tentative engagement with the African National Congress dates back to 1927 when J.T. Gumede headed the ANC, at the same time that Stalin was insisting that the Chinese Communist Party be part of, and subordinate to, the Kuomintang, the Chinese Nationalist Party then headed by Chiang Kai-shek, who was even made an honorary member of the standing committee of the Communist International. But once he marched into Shanghai in April 1927, Chiang carried out a bloody purge of Communists and set off a “white terror” in which 300,000 CPers and militant workers were killed. In South Africa, the same Stalinist “strategy” turned out to be not a “road to socialism” but the road to the Marikana massacre.

The policy of revolution in stages in colonial and semi-colonial countries has served to promote petty-bourgeois or bourgeois layers to become a new capitalist ruling class, and has over and over again led to defeat for the working class and its allies. In contrast, Leon Trotsky’s perspective of permanent revolution held that in the present epoch, the indigenous bourgeoisie is so bound up with reaction and imperialism that even democratic tasks such as national emancipation and agrarian revolution require that the working class take power, backed up by the peasantry, and proceed to international socialist revolution. This was what the Bolsheviks led by Lenin and Trotsky carried out in Russia’s Red October of 1917.

Not the ANC Freedom Charter But Workers Revolution

Metalworkers

union leader Irvin Jim. (Photo:

Mail & Guardian)

Metalworkers

union leader Irvin Jim. (Photo:

Mail & Guardian)In South Africa today, the most advanced sectors of the working class must embrace the program of socialist revolution, and build a genuinely communist, proletarian vanguard party to lead it. This has international dimensions, for uniquely in sub-Saharan Africa, the land of apartheid, old and new, has a millions-strong working class with an industrial, mining and transportation proletariat at its core. NUMSA’s break with the ANC and the Tripartite Alliance could play an important role in this, as could its call for “discussion on previous attempts to build socialism,” for “an international study on the historical formation of working class parties” and for a conference on socialism. This will clearly pose sharp debates.

A key issue will be the whole question of the ANC’s 1955 Freedom Charter and the call for nationalization. While the current ANC and SACP leaders clearly want to get rid of any hint of nationalizations, talking instead vaguely of “socialization,” the Charter calls only for “the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry” to be “transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole.” No less an authority than Mandela himself wrote the next year that the “breaking up and democratization of these monopolies” would permit “the development of a prosperous Non-European bourgeois class.” As Mandela made clear, the call of the Freedom Charter is by no means a blow against capitalism.

Throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America, petty-bourgeois and bourgeois nationalist leaders and movements have called for and sometimes carried out widespread nationalizations – often portrayed as “socialism” – in order to provide the economic basis for a “national” bourgeoisie by later privatizing assets. Even state-owned companies under capitalism function as capitalist enterprises: just look at PEMEX in Mexico (which buys up companies in Spain) or Petrobras in Brazil (which bought Bolivian refineries, then sought to blackmail the Bolivian government) before it was semi-privatized. Coming from the mouth of Julius Malema, the former head of the ANC Youth League, calls for nationalization could even be a way of bailing out bankrupt BEE black capitalists.

Depending on the context of the class struggle, proletarian revolutionaries may intervene in struggles for nationalization of the mines, banks and energy monopolies like Sasol with demands for their expropriation without compensation. They would also warn that this would not be a simple legislative matter, since the ANC, many of whose leaders are now shareholders in these companies, might well provoke a civil war before permitting it. Such measures will require a workers and peasants government to carry them out, and imposition of workers control by the workers seizing the installations to wrench them out of the grip of the bourgeoisie as part of the fight for workers rule of society as a whole.

Another question will be the program of a “national democratic revolution,” or NDR, which NUMSA leaders with their Stalinist backgrounds still uphold, although sometimes giving it a left twist, referring to a “socialist” or “socialist-oriented” NDR (for example, in their document “Cosatu at the Crossroads” [11 August 2013]). Along with their support for the Freedom Charter, this maintains the conception of a stage prior to socialist revolution in “alliance” with bourgeois and petty-bourgeois forces aspiring to become a new ruling class. Yet Marxist analysis and historical experience going back to 1848 show that this program is bound to lead to bitter defeat for the workers as the bourgeoisie will not undertake revolutionary democratic measures.

This poses another vital subject, the nature of the Tripartite Alliance as a nationalist popular front chaining the workers movement to sections of the bourgeoisie. NUMSA documents are sharply critical of how the Alliance has turned out, but they do not oppose such a class-collaborationist political coalition on principle, quite the contrary. Yet it is crucial to understand, as experience from the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War to Allende’s Unidad Popular in Chile in the 1970s shows, that in negating the political independence of the proletariat the popular front is a roadblock to revolution. It is, as Trotsky put it, “the main question of proletarian class strategy for this epoch” and “the best criterion for the difference between Bolshevism and Menshevism.”

In fact, in taking the ANC to task for resisting “the reconfiguration of the Alliance into a strategic political centre,” and in proposing “the establishment of a new United Front” to coordinate struggles “in a way similar to the UDF of the 1980s” as well as to “fight for the implementation of the Freedom Charter,” NUMSA is suggesting that a new, slightly more left-wing version of a popular-front alliance be built, one that is not simply a rubber stamp for government policies, as an “alternative” to the discredited Tripartite (ANC-SACP-COSATU) Alliance. But what is necessary in order to free South African toilers from poverty and centuries of degradation is to break with popular-frontism and to fight now for workers power.

Beyond programmatic issues, there is the question of the labor bureaucracy, a relatively privileged petty-bourgeois layer that sits atop the unions and ties them to bourgeois politics. While the NUMSA leadership’s break with the ANC is important and may provide an opening for revolutionary intervention, structurally and socially they are little different than the COSATU tops. It is undoubtedly true that the SACP and ANC got NUMSA ally Zwelinizima Vavi suspended as COSATU general secretary (almost exactly on the first anniversary of the Marikana massacre) because of his criticisms of their pro-big business policies. But Vavi’s defense against charges of using union funds to pay for a trip for him and his family to a Cape Town Jazz Festival was that the expenses were supposed to be paid for by an investment bank.

For his part, NUMSA’s general secretary Irvin Jim, his tough talk against capitalism notwithstanding, is also chair of the NUMSA Investment Company board of directors. And despite his insistence against the SACP that the state is still capitalist, he has threatened to go to the capitalist courts to “seek justice” against the SACP for defamation (“NUMSA National office Bearers’ Statement,” 1 December 2013).

As for the SACP’s defense of the ANC and its policies, these

supposed “communists” –reformists since the 1930s – have

become part of the capitalist government machinery. Moreover,

the SACP has its own capitalist investment fund,

Masincazelane, with holdings in at least a couple of platinum

mines, as well as in the Gautrain (a high-speed rail link

between Pretoria and Johannesburg) which the party had

criticized as a costly boondoggle and for bypassing the black

townships. Yet SACP deputy general secretary Jeremy Cronin, as

deputy transport minister, handed over the permit allowing the

train to operate for the 2010 soccer World Cup. Justifying his

about-turn, Cronin told the Mail & Guardian (17

May 2012) he didn’t want to be a “party pooper.”

Build a Revolutionary Workers Party on a Leninist-Trotskyist Program

That was then:

SACP deputy secretary general and deputy transport minister

Jeremy (“no party pooper”) Cronin and ousted COSATU general

secretary Zwelinzima Vavi. (Photo:

Mail & Guardian)

That was then:

SACP deputy secretary general and deputy transport minister

Jeremy (“no party pooper”) Cronin and ousted COSATU general

secretary Zwelinzima Vavi. (Photo:

Mail & Guardian)Of the political groups to the left of the governing coalition, perhaps the most notable is the Democratic Socialist Movement (DSM). The DSM was actively involved with the independent workers committees which led the Marikana workers’ struggle earlier that year, aiding them against the blatant strikebreaking actions of the violently pro-government leaders of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the SACP. Seeking to capitalize on this work, in December 2012 the DSM together with the Marikana committees launched the Workers and Socialist Party (WASP). However, the kickoff was a flop, as what was initially planned as a rally in a sports stadium turned into a “quiet” and “modest” meeting “with just 20 delegates present” (DSM press release, 17 December 2012).

While DSM members have been subject to repression, outrageously arrested in Rustenberg by police acting at the behest of the SACP and NUM, and it claims the WASP will not just be involved in elections, the new formation has been built essentially as an electoral vehicle. This is in keeping with the practice of the international tendency with which the DSM is affiliated, the Committee for a Workers International (CWI) led by Peter Taaffe.5 For over two decades the British section of the CWI was buried in the Labour Party. In South Africa, the DSM’s predecessor was the Marxist Workers Tendency of the ANC. In Mexico, Pakistan and elsewhere, the CWI has no compunction about being part of capitalist parties.

Moreover, the WASP has explicitly endorsed the “tactic” of dragging COSATU into the bosses’ courts to overturn the suspension of Vavi as its secretary general (WASP open letter to NUMSA Congress, 13 December 2013). This is a betrayal of working-class independence by Vavi’s supporters, as is WASP’s approval. Internal disputes must be settled within the workers movement, not by appealing to the class enemy. Any Marxist knows that the courts are not neutral, yet here are these supposed socialists calling on the repressive organs of the capitalist state to rule against a workers organization. For shame!

Today, the DSM and WASP seek to exploit discontent with the ANC/SACP/COSATU Tripartite Alliance which is repressing the workers. But in 1994, their predecessor called to vote to put the ANC under Mandela into office, as the petty-bourgeois nationalist movement turned into a full-fledged bourgeois party. Speaking in New York in May 1994, Peter Taaffe opposed the call for a workers party, saying: “The working class in South Africa has to go through the experience of an ANC government. The slogan of a workers party was an incorrect slogan in the period prior to the elections in South Africa. We wanted the biggest possible ANC majority.”6

The DSM/WASP continues this policy today, forming an electoral alliance Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters. The populist EFF is a bourgeois political formation, which in its Founding Manifesto (July 2013) looks to repressive capitalist regimes such as Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea as models for South African development, and calls for industrialization by mining and manufacturing “entrepreneurs” (capitalists), etc. Moreover, the EFF declares that “the police are not our enemy” and seeks to “build strategic and working relationships with the cohesive components of the state, particularly the military and the police.” But this counterrevolutionary line is not the EFF’s alone.

For genuine Marxists, the concept of a class line is key. We seek to build revolutionary workers parties against all bourgeois parties and politicians. Social democrats like the DSM and CWI, or Socialist Alternative in the United States, on the other hand, and reformist Stalinists like the SACP, seek to gain influence in the capitalist state, contradicting everything that Marx, Engels and Lenin wrote about its nature as an instrument of suppression of the workers by the bosses, no matter who is in the government. This question comes to a head over the matter of the police, the backbone of the state, who carried out the massacre at Marikana. For the CWI, the police are “workers in uniform” rather than the armed fist of the bourgeoisie.7

And not just under the ANC. The MWT’s Congress Militant (September 1993) ran an interview with the deputy president of the Police and Prisons Civil Rights Union (POPCRU), “comrade Enoch Nelani,” calling for these enforcers of apartheid law and order to be admitted to COSATU (they were). And CWI guru Taaffe in his 1994 speech marveled that “black cops in South Africa who mowed down workers organizing trade unions” are now “organized into a trade union themselves.” He went on: “These very same killers, these very same black police who were tools of the apartheid regime, were radicalized by the situation.” His conclusion: “We can neutralize the forces of the state and win them over.” So much for State and Revolution.

It’s a straight line from there to the marikana massacre. We agree with Trotsky, who wrote in his pamphlet What Next? Vital Questions for the German Proletariat (1932): “The worker who becomes a policeman in the service of the capitalist state, is a bourgeois cop, not a worker.” We demand, cops out of the unions! When the DSM/WASP calls for a “mass workers party on a socialist programme,” they mean a social-democratic party with a Labourite program to reform the capitalist state. The League for the Fourth International calls for a Leninist-Trotskyist workers party on the program of permanent revolution. Between these two sharply counterposed positions runs the line between Menshevism and Bolshevism.

There are many thorny tactical issues facing revolutionaries in South Africa today, including the position to take towards COSATU. Earlier some leftists were pushing for workers to leave COSATU, while others were even trying to cajole miners back into the NUM, which had unleashed the murderous repression. Trade-union unity is not an absolute principle. Where there are splits in the bureaucracy that offer an opening for revolutionary Marxism, authentic Trotskyists would seek to intervene. But in whatever trade union or labor federation, we fight to build a class-struggle opposition to oust the pro-capitalist bureaucracy, opposing popular fronts and class collaboration in every guise, seeking to lay the basis for workers councils (soviets) that can be the organizing centers for workers revolution.

The Marikana massacre in South Africa could have the effect that the Bloody Sunday massacre of January 1905 had in tsarist Russia, of crystallizing mass indignation and awakening the working class to struggle, touching off the 1905 Russian Revolution. If so, this upsurge will be held back, not aided, by reformist electoralist parties that seek to maneuver with the bourgeoisie. Only unyielding struggle for the program of international socialist revolution can take the struggle forward, to a united socialist states of Africa and a socialist world. ■

- 1. NUMSA represents auto and steel workers, while the NUM (National Union of Mineworkers) had grown so close to the mine bosses that at Marikana it called for the bloody suppression of its own striking members.

- 2. See “South Africa: Bloody Mine Massacre Unmasks ANC Neo-Apartheid Regime” (29 August 2012), reprinted in The Internationalist special issue, November-December 2012.

- 3. The coloured population, often referred to as mixed race, is predominant in the Western Cape province.

- 4. Under apartheid South Africa was, by far, the most unequal country in the world in terms of income distribution, and is even more so today. South Africa’s Gini coefficient, in which total inequality (one person has all the income) would be 1.0, rose from .64 in 1994 to .70 in 2008.

- 5. See “‘Socialist’ Elected in Seattle on Platform of Liberal/Populist Reforms,” in this issue.

- 6. Quoted in Workers Vanguard No. 602, 10 June 1994, at a time when WV was the voice of revolutionary Trotskyism.

- 7. See “Her Majesty’s Social Democrats in Bed with the Police,” in The Internationalist No. 29, Summer 2009.

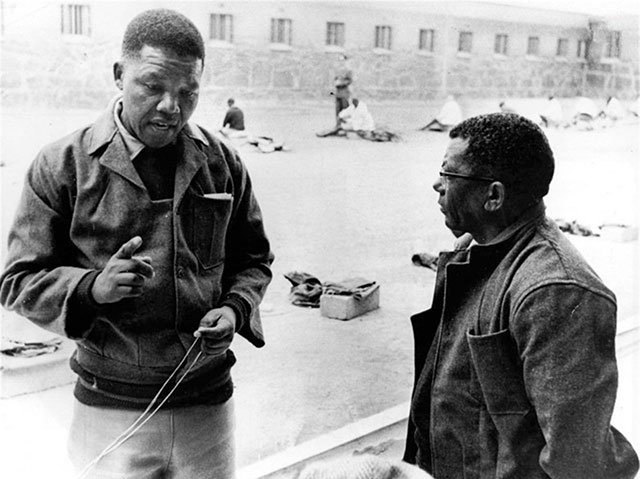

Nelson Mandela, 1918-2013

ANC leaders Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu in Robben Island prison, 1986.

(Photo: UWC Robben Island Museum/Mayibuye Archive)

The following article is translated from the upcoming issue of Vanguarda Operária, the newspaper of the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista do Brasil, section of the League for the Fourth International.

6 DECEMBER 2013 – At the close of 2013, South Africa has lost Nelson Mandela, one of the most decisive men in that country’s life over the last hundred years, almost a century – roughly the same duration as his life of trials and tribulations – bringing international expressions of sympathy and support due to the scope of his struggle. Mandela suffered persecution and torture of every sort, which only someone with the build of a boxer, which he was, could have withstood. Those who planned and maintained the racist South African apartheid system searched the world, in the best schools, looking for human beings who had been turned into monsters. Many Nazis and fascists gave classes on torturing black men and women activists in particular.

At the head of the African National Congress (ANC), held in the dungeons of the apartheid regime for 27 years, Nelson Mandela stood out and was the biggest personal symbol of resistance in the struggle against apartheid. He aided and came to symbolize the main confrontations of the political struggle against the racists. He was present practically from the beginning, the middle and the end of the aggressive white racist regime embedded in a multitude of 75% blacks, 12% coloureds (mixed race people) and Asians facing an oppressive and privileged layer of 12% whites. At the same time, today Mandela is almost universally hailed as the symbol of “reconciliation,” including by the capitalists and imperialists who supported and profited from the system of apartheid slavery up to the end.

Mandela’s almost century-long resistance without a doubt prevented many from abandoning the struggle. This tenacity, longevity and capacity to bear the struggle in such unequal conditions was inspired in the first place by the capacity of the black population to have experienced, confronted and overcome centuries of chattel slavery on the African continent and beyond. It was there in South Africa that the courageous Zulus defeated the English colonial troops. The Ethiopians with bows and arrows put the Italian fascists on the run, expelling them from their country, humiliating Mussolini and Hitler.

The ANC and Mandela doubtless had contact with the literature that narrated the heroic deeds of Zumbi dos Palmares in Brazil and Toussaint Louverture in Haiti, the greatest expressions in the “New World” of the arduous, protracted and cruel struggle against the enslavement of human beings when this was revived in the Americas in a historical retrogression, since mass slavery had already ended more than five centuries earlier with the fall of the Roman Empire. Palmares, the republic of escaped slaves, resisted for a century and the Haitian revolutionaries inscribed their names in the annals of human history by defeating the powerful army of Napoleon and the other slave powers of the time. Haiti became the only country in the world where there was a victorious slave revolution.

Mandela had rich sources of inspiration and incentive. The South African Communist Party with the support of the former Soviet Union and Cuba provided organization, material and logistical support to the struggle of the ANC, without which apartheid might have survived. But history will also register that Mandela, the South African Communist Party and the ANC did everything possible to keep the struggle against racism in that country confined to the framework of capitalism and bourgeois democracy. As a consequence, the black and coloured population today still lives in poverty, in the racist system of neo-apartheid today presided over by the bourgeois popular front of the ANC, CP and the union bureaucracy which upholds the economic domination of the white capitalists.

Mandela’s policies headed up free-market black capitalism within the African National Congress. The class collaboration of the South African popular front prevented socialist revolution in that country, which at various points was entirely possible to achieve, a success that would have spread throughout the continent, delivering its population from terrible suffering and turning the continent into a federation of socialist countries.

Nelson Mandela will probably join the pantheon of African heroes given the international scope that his struggle against the hated South African apartheid achieved. At the same time, he joined those political symbols who, however shining they might seem, turn out to be an empty shell. These are the cases of the former workers Lech Walesa (Poland) and Lula (Brazil), of the Indian Evo Morales (Bolivia), of the black man Barack Obama (U.S.) and similar cases, like the women Michelle Bachelet (Chile) and Dilma Rousseff (Brazil), who may wrap themselves in the most beloved banners of the exploited and oppressed, while their policies lack any revolutionary character and thus they have only managed to prolong the life of capitalism.

The results of the class collaboration of the South African popular front are terrible. The end of apartheid gave way to and prepared the way for the brutal capitalist exploitation and oppression of the country, now governed by an inter-ethnic caste of whites and rich blacks, icons of “neo-liberalism” of the post-Soviet period on the continent, proving for the umpteenth time that the popular front is a danger for the working class! Proof of this is the terrible massacre of the miners at Marikana last year by the police of the popular-front government. The liberation of the black population will only come about through socialist revolution. ■