No. 14, January 2018

For Labor/Black Mobilization Against Racist Cop Terror

Trump’s Racist Vendetta

Against Black Athletes

Black players on the Houston Texans “take a knee” during the national anthem before a game on 29 October 2017 to protest racist repression. (Photo: Elaine Thompson/AP)

By Dan

An abbreviated version of this article was published in Revolution

No. 14 (January 2018), published by the Revolutionary

Internationalist Youth and the Internationalist Clubs of the

City University of New York.

Donald Trump has been on a racist tear this season, engaged in an furious vendetta against protesting black athletes of the National Football League (NFL). It started in 2016 when Colin Kaepernick, then quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, refused to stand for the “Star Spangled Banner” in protest against the ongoing racist police murders of black and Latino people. As we wrote at the time:

“It never stops. As protesters chant ‘say their names,’ the list is unending of those killed for the ‘crime’ of being black in the racist U.S.A. No wonder what the media call the ‘Kaepernick effect’ keeps spreading.”

–“Courageous Kaepernick Protest Inspires Youth Defying Racist Repression,” Revolution No. 13, September 2016Kaepernick was joined by a number of other players, which started a chain reaction, with athletes from professional soccer teams, college and high-school football teams joining the protest.

This was followed by a predictable racist backlash, with analysists browbeating protesting players to “focus on football” instead of speaking out against the police murders of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and so many others in this country built on slavery. Kaepernick did not back down, and is out of a job as a result. After being kept on the bench all season, he “opted” to become a free agent so that he might have the chance to play somewhere else. According to 49ers General Manager John Lynch, he would have been released anyway:

“Yes, he was not going to be here under the construct of his contract. We gave him the option: ‘You can opt out, we can release you, whatever.’ And he chose to opt out, but that was just a formality.”

Kaepernick has been blacklisted by the NFL – no team signed him in 2017 because of his activism, even though having such a top quarterback could have been transformative for many teams in the league. Despite this blatant attempt to silence him, the “Kaepernick effect” hasn’t gone away. From the start of the season, players from multiple teams refused to stand for the national anthem, angering Trump and eliciting near-weekly tweets about how they should be penalized or fired.

On September 22, the racist-backlash president asked a crowd at a GOP primary rally in Alabama if they’d “love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, he’s fired!’” The racists went hog-wild and were energized by this. But protesting players were galvanized.

By September 24, scores of players on just about every NFL team were taking the knee, including 32 from the Denver Broncos and 27 from both the Baltimore Ravens and the Jacksonville Jaguars at a game in London, England. High school football players from New Brunswick, NJ to Vancouver, WA joined in the protest, as did cheerleaders at a number of schools.

Indianapolis Colts “take a knee” during the national anthem before a game on 24 September 2017.

(Photo: USA Today)

But there were also reprisals: protesting student athletes in Texas were kicked off their team, while schools threatened others. On October 8 Trump sent his toady, VP Mike Pence, to his home state of Indiana to walk out of an Indianapolis Colts game to “protest the protestors.” When Oakland Raiders running back Marshawn Lynch sat for the “Star-Spangled Banner” and stood for the Mexican national anthem at a November 19 game in Mexico City, Trump foamed at the mouth, insisting that he be suspended.

In contrast to black players protesting racist police murder Trump notoriously said there were “very fine people” among the fascist, white-supremacist Klansmen, Hitler worshipers, Confederate slavocracy defenders and racist trolls at the Charlottesville, Virginia “Unite the Right” rally a month prior. Stoking his racist vendetta against black athletes, on September 25 he tweeted “the issue of kneeling has nothing to do with race. It is about respect for our Country, Flag and National Anthem.”

When Houston Texans owner Robert McNair said “we can’t have the inmates running the prison” at an owners’ meeting in October, referring to the players, what he was saying is “we can’t have the slaves running the plantation.” It is obvious that the protest against police murder has everything to do with racist repression. What Trump has shown is how patriotism is whipped up in the service of racist reaction.

The protests of 2017 were not just a replay of 2016. They became more widespread in response to Trump and his blatant racism. There were also attempts by team owners and others to “broaden” the protests in order to soften the impact and to take the focus off police brutality. A prime example was two black police locking arms with Cleveland Browns players before a September 10 game. There were attempts to reinterpret the meaning of the protests – linking arms is different from kneeling, which is different from sitting out the anthem altogether. Some of those kneeling are pro-military, and Kaepernick originally changed his protest from sitting to kneeling as a way to “show more respect” to the military. As we wrote in 2016:

“Showing ‘support for the troops’ is a standard way that the powers that be try to ‘mainstream’ protests and channel them into expressing loyalty to the imperialist rulers who lure youth from the working class and oppressed communities into their armed forces to kill and die for their profits.”

The owners tried to divert attention from the original meaning of the protests by offering to donate $90 million to charities. From the high point in week three of the season, when over 100 players protested, the numbers dwindled. But some held out alone, including Olivier Vernon of the New York Giants. The hard core (like Miami Dolphins wide receiver Kenny Stills) insisted that their courageous act was “to raise awareness about police brutality and other systemic injustices, and the fact that those problems disproportionately affect black Americans” (Bleacher Report, 3 January).

In fact, the number of killings civilians by the police has remained almost identical year after year. Last year there were 1,188 people killed by cops – that’s more than three a day – and those are only instances which have been reported in the media: the actual number is doubtless substantially higher. Part of the reason for the prominence of protests by black players has been the dearth of mass protests like those in 2014 and the beginning of 2015. Why? A key factor is that many of the main leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement have channeled support into the Democratic Party and diverted the protests into electoral politics (like DeRay Mckesson running in the Democratic primary in Baltimore and Tishuara Jones in St. Louis).

There should be tens of thousands in the streets mobilized against racist police murder. The black players of the NFL should not be alone in carrying the torch of protest. But to actually have an effect requires much more, above all breaking the political stranglehold of the partner parties of capital. As we wrote in our article on Colin Kaepernick, “only the international revolution of the working class, at the head of all the oppressed, can uproot forever the legacy of slavery symbolized by the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and end the present-day nightmare of unending racist repression.”

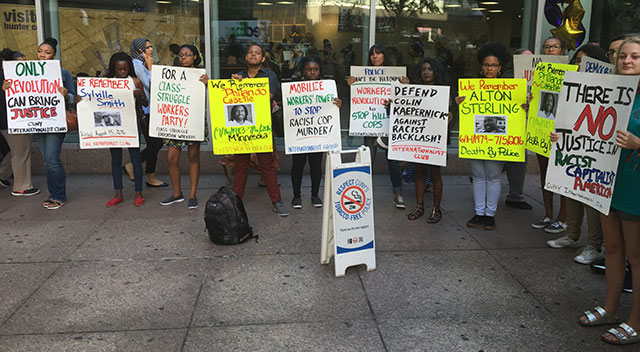

There should be tens of thousands in the streets protesting racist police murder. Speak-out against racist terror called by Internationalist Clubs at the City University of New York, Hunter College, 30 August 2016).

(Internaitonalist photo)

The Kaepernick Effect in 2017

Football players “taking a knee” is all about racial oppression, and the athletes protesting know this very well. Responding to those who use patriotic demagogy to attack athletes for “daring” to oppose racism, Philadelphia Eagles wide receiver Torrey Smith said that even though his father is a U.S. Army veteran, that “doesn’t protect him” from racism. And Trump tries to whip up racist hysteria with his super-patriotic appeals even as he notoriously made dismissive remarks to the widow of black Army Seargent La David Johnson, who was killed after being sent on one of U.S. imperialism’s under-the-radar missions in Niger.

Trump is so ignorant of history that he thinks Frederick Douglass is still alive (as he showed in his Black History Month statement), In fact, there is a proud tradition of black athletes protesting racism – from John Carlos and Tommie Smith raising their fists on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics, to boxing legend Muhammed Ali going to prison for refusing to fight in the U.S. imperialist war against Vietnam.

It’s the oldest trick in the book for reactionaries to play the patriotism card in their attempt to stop people from telling the truth about the systematic racism being protested. And not just in the United States: when French soccer great Zinedine Zidane, of Algerian descent, as well as other players on the French national team Les Bleus refused to sing “La Marseillaise” to protest France’s racist colonial legacy in Algeria, the fascist National Front went ballistic.

Karl Marx famously wrote in the Communist Manifesto that “the workingmen have no fatherland.” The capitalists need the working class to identify its own interests with those of capital in order to sustain bourgeois class rule. As we wrote in our article on the Kaepernick protests:

“In reality, one of the key purposes of sports spectacles has been to whip up patriotism, in order to divert the working class. We just saw that again with the Olympics, when people chant ‘U.S.A., U.S.A.,’ athletes like Simone Biles drape themselves in the American flag, and the media count how many medals ‘our country’ has won. Then there are the endless brawls by fans of the British, French, German and other soccer teams, with ‘soccer hooligans’ providing recruiting grounds for rightist goon squads.”

In a totally cynical, transparently opportunistic gesture NFL commissioner Roger Goodell called Trump’s “SOB” comment against the protesting players “divisive” – a criticism frequently levelled by Democrats and liberal commentators. He wasn’t the only one. New York Giants owners John Mara and Steve Tisch called Trump’s comments “inappropriate, offensive, and divisive.” Robert Kraft, owner of the New England Patriots and a friend of Donald Trump, was “deeply disappointed by the tone” of what Trump said. Nearly every NFL team owner, CEO or president denounced Trump’s remarks in one form or another. But this was hardly due to any kind of opposition to racism, police violence or to Trump.

No, it was about cold, hard cash. An environment where the owners and their employees – the players – are publicly pitted against each other is bad for profits. The NFL Players Association (NFLPA) has a combative history and has caused headaches for the owners in the past. The players went on strike in 1974, again in 1982 (disrupting most of the season) and again in 1989. There was a lockout in 2011 in which the owners locked players out of facilities after the expiration of the 1993 collective bargaining agreement (which had been renewed four times up until then). The owners wanted a bigger cut of NFL revenues at the expense of the players’ share, to extend the season from 16 to 18 games, and to impose a rookie salary cap.

At one point the owners tried to co-opt the protests: some of them symbolically locked arms with their players before a Sunday night game on September 24, two days after Trump made his racist comments. But two weeks later, after Trump’s incessant scolding of the league and team owners, they reversed course, with Cowboys owner Jerry Jones in the lead saying he would bench any player if they “disrespect the flag.” This came one week ahead of a meeting between the owners and NFLPA to discuss the “social issues” pertaining to protests.

A joint statement by the union and the league said “NFL executives and owners joined NFLPA executives and player leaders to review and discuss plans to utilize our platform to promote equality and effectuate positive change.” The very idea that there should be a “joint statement” between the bosses and players was an attempt to take the focus off police murder. The owners want to diffuse the protests by generalizing them with talks about “promoting equality.”

As capitalists, their solution is always to throw money around. They proposed a payout of $90 million to be donated over the course of five years “to social causes deemed important by the players, focused in particular on African American communities,” according to a Washington Post (30 November 2017) report. This is essentially hush money, offered to the players’ NGOs of choice to try to curb protests. The deal was approved by the Players Coalition, a group representing protesting players in the NFLPA, and will be taken up by the owners in their annual March meeting.

The rank hypocrisy behind this maneuver is hard to miss. Jacksonville Jaguars owner Shahid Khan linked arms with his players before a game in London in September. But Khan donated $1 million to Trump’s presidential campaign. Robert Kraft also donated $1 million dollars to Trump, and was a vocal supporter during his presidential bid.

Meanwhile, Texans owner Rob McNair (“can’t let the inmates run the prison”) is chairman and CEO of the McNair group, one of Houston’s largest real estate developers. When Hurricane Harvey hit southeast Texas in August, the black residents of Houston disproportionately suffered major flooding – a result of profit-crazed real estate moguls building on floodplains.

Some players saw this hush money for what it was and resigned from the Players Coalition, including Miami Dolphins safety Michael Thomas and 49ers safety Eric Reid, who had knelt side by side with Colin Kaepernick in August 2016. The negotiations between the League and Players Coalition were carried out on behalf of the players by Philadelphia Eagles defensive back Malcolm Jenkins and former 49ers receiver Anquan Boldin. Reid was angry with how Jenkins carried out the negotiations behind the membership’s back, and also how he unilaterally cut off Kaepernick from the Players Coalition.

While popular culture portrays professional athletes as being larger than life, the fact is that their work on the field, with all the pain and wear-and-tear that are packed into their relatively short careers, make possible the extravagant profits reaped by NFL team owners. In 2016, the league brought in $13 billion in revenue and distributed $7.8 billion to its 32 teams, which is about $244 million per team. The owners are making big bucks, and Trump figures he can whip them into line by threatening them in the pocketbook.

Black Athletes – A Favorite Target for Racist Reaction

Part of the racist backlash against these players is the argument that they should be “grateful” for being “given” the opportunity to make good money – something the racists believe should be reserved for “their own kind” – and be adored by the masses. Former Republican congressman Newt Gingrich, always eager to fan bigotry, said, “If you’re a multimillionaire who feels oppressed, you need a therapist [and] not a publicity stunt.” This timeworn argument in the arsenal of racist apologia amounts to telling professional athletes they could have easily ended up dead, in jail, or living paycheck to paycheck, so they better shut up and act happy This takes for granted exactly what the players are protesting, which is the racist oppression endemic to U.S. capitalism.

The fact that the protests have continued has left Trump fuming, and he has turned his vendetta against black athletes into a hobby horse. Trump went ballistic when basketball star Stephen Curry of the Golden State Warriors told the media on September 22 he didn’t want to go to a White House meeting honoring the championship team, for which the date had not been set. In response, Trump “rescinded” his invitation to Curry and the Warriors, for which LeBron James called Trump a “bum.”

James has taken the lead in protesting racial oppression ever since he brought out the whole Miami Heat team in hoodies at a 2012 game to protest the murder of Trayvon Martin by a racist vigilante. In December 2014, LeBron (by then back on the Cleveland Cavs) wore an “I Can’t Breathe” shirt during warmup before a game with the Brooklyn Nets, recalling the last words of Eric Garner as he was being choked to death by an NYPD cop. The game was attended by Prince William and Kate Middleton of the British royal family.

The media claimed to be outraged over James breaking “protocol” in a photo-op with the royals. But what really got them was the message on his shirt. However, they were afraid to make a stink about it directly in the heart of downtown Brooklyn, in the middle of a winter of protests that brought out tens of thousands enraged by the choke-hold murder of Garner. Many of the protests were led by his courageous daughter Erica who recently died of a heart attack, directly related to the trauma that she had been put through.

Many people angered by Trump’s racist tirades are looking to the Democrats for a solution. But Eric Garner was murdered by the NYPD under Democratic mayor Bill de Blasio, who appointed the infamous Bill Bratton as his police chief. Bratton was the godfather of “broken windows” policing – the policy of aggressively enforcing laws against “quality of life” crimes like public drinking and begging. It was the original rationale for “stop and frisk,” which codified the racist practice of random searches of African Americans and Latinos on the street. Freddie Gray was likewise killed under the Democratic city administration of Baltimore, headed at the time by Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, the city’s second black woman mayor, who railed against “rioters” as “criminals” and “thugs” in the 2015 protests following Gray’s murder.

The protesting athletes of the NFL are using their place in the public eye to draw attention to the oppression faced by black and Latino people in this racist country. But symbolic protest alone will only go so far – to uproot racism requires the revolutionary mobilization of the multiracial, multiethnic working class, bringing together all the fights against oppression to bring down the capitalist system, which breeds and lives off racism. To defeat racist oppression once and for all – and to put a stop to the monstrous plague of racist police murders – will take nothing short of a socialist revolution. ■

NFL: Players Are Expendable, Profits Are Not

While Donald Trump claims that player protests are hurting ratings and attendance in the National Football League, basketball Hall of Famer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar recently predicted that the brutality of football will drive people away from the NFL toward the National Basketball Association (NBA). Safety was a major issue for the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) going into the 2011 lockout, and the specter of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) still haunts the League and its commissioner Roger Goodell. Seeing how the owners have considered players’ brains as expendable, you get a sense of how much they consider the players virtually a form of property to be tossed aside on a profit/loss basis.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disease found in people who have experienced repeated head trauma. It can lead to behavioral problems, cognitive impairment, depression and dementia. Former NFL star Dave Duerson suspected he may have had CTE when he committed suicide in 2011, and left a note requesting that his brain be donated to researchers studying the condition at Boston University School of Medicine. It turned out that he had CTE.

In 2012, retired NFL player Junior Seau also committed suicide, and studies of his brain showed that he too had been suffering from CTE. A study published in the medical journal JAMA found that CTE was present in 99 percent of donated brains from ex-NFL players (“Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football,” 25 July 2017). Another study published in Neurosurgery (November 2017) confirmed a diagnosis made four years ago in a then-living retired player.

The ability to diagnose CTE while people are still alive is a key scientific breakthrough, as diagnoses were previously only possible through autopsies. One of the scientists behind the Neurosurgery paper is Dr. Bennet Omalu, a Nigerian American forensic neuropathologist who first discovered CTE in former Pittsburg Steelers Hall of Famer Mike Webster in 2002, while working for the Allegheny County Coroner’s Office. In fact, the NFL had tried to hide the connection between repeated head trauma and brain injury for years.

In 1994 the League formed the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) committee to study brain injuries in NFL players amid increased public awareness about concussions. In 2005, former Pittsburg Steeler Terry Long committed suicide. When Omalu examined his brain and found CTE, the MTBI committee tried to discredit his findings linking Long’s suicide to CTE. For years, the committee had sponsored bogus studies claiming NFL players were not at greater risk for head injury and disputed the negative effects of repeat concussions. In 2004 they went so far as to claim that NFL players had evolved a greater resistance to head injuries:

“certain individuals undoubtedly are more prone to MTBI than others.… It is likely that many of these individuals will stop playing organized football before reaching the professional level.… [T]hose players who ultimately play in the NFL are probably less susceptible to MTBI.…”

–“Timeline: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis,” PBS Frontline, 8 October 2013

The NFL changed its tune in 2009, when after a series of PR disasters culminating in a House Judiciary Committee hearing on concussions in football the League was forced to accept the overwhelming scientific evidence linking repeated head trauma to brain injuries.

Since then, it has settled a $765 million class-action lawsuit with 4,500 players and their families and adopted some cosmetic changes, but the problem of head injury remains. When Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman was asked about how the League was dealing with head injuries, he replied:

“No, the League hasn’t done much outside of appeasing public opinion. Now, you get a hard hit, fine players a bunch of money, suspend guys. But it’s more punishing players than it is player safety, and putting more money into league charities, etcetera. It’s not really changing the game or making it more safe.”

Appeasing public opinion while putting the onus of safety on the players is precisely what the NFL owners and commissioner want, so they can keep milking the football cash cow.

Crises over player safety in football are not new. There were calls to ban the sport entirely in the early 1900s, when the game was so brutal that it was likened to a killing field. According to The Washington Post, at least 45 players died from 1900 to October 1905, 18 of them in 1905 alone (and at least 45 players were injured playing the game that year).1 Universities began suspending their football programs (Columbia, Duke and Northwestern for example). President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in to “save” football, calling in coaches from Harvard, Yale and other schools to the White House “with a view to such modifications of the rules as would eliminate its brutal features.”

In 1939, plastic helmets became required for college football players, and in 1956 were redesigned to include face masks. In the 1960s plastics were improved so that helmets did not shatter as easily, and in the 1970s inflatable bladders were added to the inside of helmets for shock absorption. These innovations made it less common for players to fracture their skulls and/or die while playing the game, but long-term damage is obviously still a major issue. The American Academy of Pediatrics called to ban tackling from youth football in 2015. That same year 17-year-old high-school football player Andre Smith in Chicago died because of injuries sustained in a game.

Whether or not football can really be made safe is a matter of controversy. What’s for sure is that in a rational society, people’s brains would not be merchandise to be discarded after too much profit-generating wear and tear. ■

- 1. “How Teddy Roosevelt helped save football,” The Washington Post, 29 May 2014.