October 2025

Immigrant Worker Organizer and Revolutionary

Remembering Our Comrade Fernando López

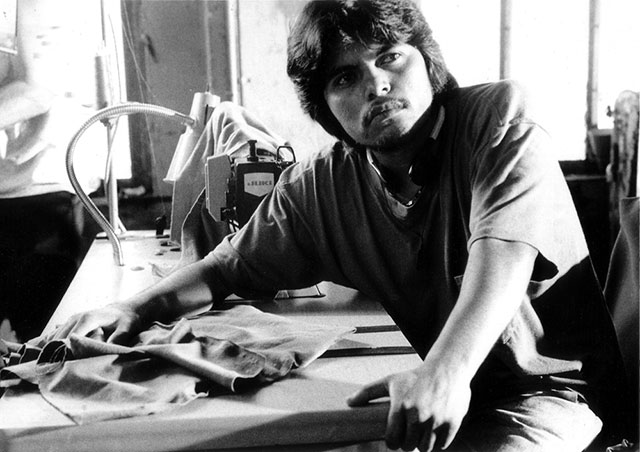

In director David Riker’s 1998 film La Ciudad, based partly on Fernando’s own experiences as an immigrant garment worker, he portrayed a participant in a work stoppage to defend a seamstress abused

by bosses in a New York City sweatshop.

As the youth section of the Internationalist Group (IG), the Revolutionary Internationalist Youth draws on the IG’s history of bringing the revolutionary working-class program of Trotskyism into the struggle to defend immigrant rights. As the struggle intensifies today, part of educating ourselves is knowing this history. Our late comrade Fernando López embodied many important aspects of it, as shown in the following article that we are reprinting from The Internationalist No. 7, April-May 1999, where it appeared under the title “Fernando López, 1973-1999: Comrade, Internationalist, Revolutionary.”

Our comrade Fernando López died in a tragic subway accident in New York City on 4 April 1999. Fernando was 25 years old; he was a garment worker, a union organizer, an activist in the cause of the oppressed, and a communist. He was a worker intellectual, a talented organizer and recruiter of remarkable energy and enthusiasm. As a close friend wrote in his memory: “In your short life you left your mark profoundly on all of us who had the pleasure of knowing you.” A memorial meeting was held for Fernando in Manhattan on April 13, attended by 100 people, with more than a dozen speakers.

Fernando López Inzunza was born on 15 July 1973 in Huajapan, in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. As a child he moved to a small town in the state of Tlaxcala, and as a teenager went to Mexico City, where as a high-school student he developed a deep interest in mathematics and helped organize a number of cultural and political youth groups, making plans to study drama on a scholarship he had won from the Instituto de Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Institute). However, in 1994 he followed relatives who, like thousands of others from the Tlaxcala-Puebla region of Mexico, went to New York in search of work. Fernando’s uncle had gotten work in a Brooklyn sweatshop (where he met and married a Ukrainian woman of Jewish origin); and soon Fernando was making his living as a sewing machine operator in the garment trade.

The conditions of merciless exploitation of the thousands of “undocumented” immigrants who, like Fernando, worked for miserable wages in dark, poorly ventilated and often unheated sweatshops aroused his indignation and spurred his developing social consciousness. He soon joined efforts to bring his fellow workers into the garment workers union (first the ILGWU and then its successor union UNITE), which had begun a number of organizing drives among immigrant workers. In June 1995 he was chosen to represent the garment workers of Manhattan at a demonstration of hundreds of workers in support of Chinese sweatshop workers in Brooklyn. In his speech, “in the name of the workers of all nationalities,” he denounced the way “the bosses and contractors exploit us mercilessly and trample our dignity and respect.”

As part of a group of union activists he was later sent on a months-long organizing drive in California, and was also assigned to assist Teamster organizing efforts at a large rental car agency. With a strong sense of irony he would later display the diploma he received when the union tops sent him to a formal training course for organizers, relating how they sought to tempt him with the bureaucrats’ “good life” by putting him up in a fancy hotel before sending him back to the sweatshop. At the same time, he stressed the impact made on him by a Korean American organizer he worked with, who put his knowledge of the Korean, Spanish and English languages to work to bring workers into the union movement.

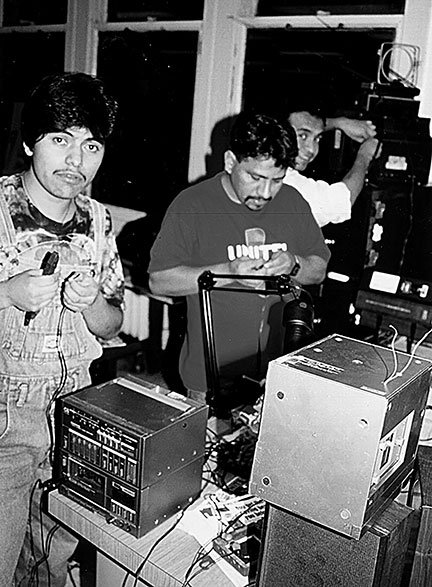

As a founder of the

Garment Workers Solidarity Center, Fernando’s knowledge

As a founder of the

Garment Workers Solidarity Center, Fernando’s knowledgeof computers and logistics complemented his talents as a working-class

educator and organizer.

When UNITE carried out a lightning purge of the group of activists and organizers Fernando was working with in New York City, he helped them found the Garment Workers Solidarity Center. In a statement to the memorial meeting held on April 13, the GWSC noted: “From the beginning he was an active member, assisting the Press and Propaganda Committee. Later, due to his knowledge of logistics and computers, he was elected to head the Organization Committee.... Fernando is an example of how a garment worker ... can develop his potential as a leader. And this is how our compañero Fernando came to show his many facets in the workers movement.”

When filmmaker David Riker, who became Fernando’s friend, made a movie entitled La Ciudad (The City), Fernando played a role as a sewing-machine operator who joins others in a work stoppage to defend a woman worker, a vivid depiction of the power of workers solidarity. In the real life sweatshops his fierce persistence and passion in his organizing work won him the nickname El Tigre.

Fernando’s development into a Marxist revolutionary was thus rooted in his previous experiences and development. As a comrade from the Internationalist Group noted at the memorial:

“Fernando López decided to fight to understand the world and change it. Fernando went through the world questioning, always questioning. He never accepted anything simply because somebody said it was so, or because that’s just the way things are. He always wanted to know why. He always wanted to know, what is it that we should do? And he never resigned himself in the face of injustice.”

This sense comes through in a piece Fernando wrote in 1994, which was read at his memorial:

“I would like to live a thousand years/in order to understand this world. In this game of life/ there are only two paths: That of an easy life/ and that of great sacrifices. I hope to have the happiness/ of walking along the second path, so that at the end of my existence/ I will be filled with satisfaction.”

Poems about Fernando were also read by a writer of popular Mexican poetry who is a member of Unimexny, and by comrade Socorro of the Internationalist Group.

A speaker from the New York Zapatistas, to which Fernando had belonged as he politically developed toward Bolshevism, stressed his insistence on orderly and productive meetings and the enormous care and attention to organizational detail he put into every aspect of his work. Understanding the importance of organization and consciousness, and of those who march in the vanguard of their class, Fernando came to a decision rooted in his previous experiences and evolution: to become a professional revolutionary, a Leninist.

At the time of his death he had formally requested to join the Internationalist Group, section of the League for the Fourth International, and was attending meetings and carrying out party assignments. This step came after working and studying with us intensively over the past period. He participated with the IG at marches and protests, and rallies for Mumia Abu-Jamal; intervened at a range of leftist events, chastising reformists who push petitions for “reforming” the police and centrists who cite opinion polls to justify their abandonment of the struggle for Puerto Rican independence; and began to participate in work among students facing the racist purge of minorities at the City University of New York.

An IG speaker noted Fernando’s “enormous passion for ideas”: “In classes over the course of 26 years, I have never seen a more enthusiastic and sincere participant or a quicker learner; and in a short time he began to give classes on various Marxist themes.” In the months before his death he helped give classes on topics ranging from Lenin’s polemic against nationalism in Critical Remarks on the National Question to Engels’ essay Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy and (using examples from his extensive knowledge of mathematics), the chapters on dialectics in Engels’ Anti-Duhring. At the same time he continued to teach GED (high-school equivalency) classes for his fellow workers. One of his students recalled how he would come straight from his back-breaking job to give these classes, insisting on students applying themselves and completing their assignments.

At the memorial, another IG comrade noted that this reminded her of Trotsky’s description of his son Leon Sedov:

“Leon had exceptional mathematical ability. He never tired of assisting many worker-students who had not gone through grammar school. He engaged in this work with all his energy; encouraging, leading, chiding the lazy ones – the youthful teacher saw in this work a service to his class.... Most of his time, strength and spirit were devoted to the cause of the revolution.”

Fernando’s tireless work to bring new people around our organization made a big impression on friends and coworkers, one of whom wrote: “You have changed a lot since you began to be part of the group of the Trotskyists. Your ideas have become clearer and better-founded. The truth is I admire you.” In Fernando, the Trotskyist movement has lost a powerful comrade just as a long period of preparatory work was bearing fruit.

For Fernando solidarity was not just a word; he lived it and in reality embodied it; in his death he received it from many, as shown by the more than one hundred people, most of them immigrant garment workers, who came to pay their respects at the funeral home shortly after his death and again at the memorial meeting. Having seen the employers seek to fan antagonisms between Asian and Hispanic workers in the garment industry, Fernando was deeply committed to the struggle to overcome racial, ethnic and national divisions among all the working people. One of his assignments for our organization at the time of his death was extensive research on the Asian immigrant worker population in the New York area.

When we met and began discussions with him in a period of demonstrations against massacres in Chiapas and immigration raids in New York, he showed a great interest in the struggle against black oppression and an understanding of its central role in virtually all social and political questions in the United States, including struggles against the oppression of women and anti-immigrant racism. Several speakers noted at the memorial that Fernando was active in the fight to free Mumia Abu-Jamal. In a poem read to the memorial, comrade Socorro recalled Fernando, “the hole in your leather jacket/covered with a button of Frederick Douglass,” as a “revolutionary with no patria” (fatherland), and quoted the Mexican revolutionary Ricardo Florés Magón. “The patria, proletarians, is something which is not ours. The patria belongs to the bourgeoisie, and thus it is they alone who benefit from it.” Long before meeting the Internationalist Group, Fernando was already calling himself “a citizen of the world.”

One of the most remarkable examples of his spirit, determination and organizing talents occurred when, together with many coworkers, he was arrested in one of a wave of Immigration and Naturalization Service raids in the New York area last year. An article on migra raids and deportations in El Internacionalista (No. 1, May 1998), the Spanish-language publication of the League for the Fourth International, begins with a description of this March 1998 raid, based on a letter Fernando wrote from jail. Twenty plainclothes INS agents blocked the doors of two sweatshops, seizing “undocumented” immigrants who worked there for minimum wage. Handcuffed and chained, the men were taken to a prison run for the INS in Elizabeth, New Jersey by the Corrections Corporation of America, the women to a migra prison in Pennsylvania. Because he refused to cooperate with the INS agents by giving his nationality and other information, or signing papers or stating his country of origin (which facilitates the deportation process), and because he sought to organize others to do the same, Fernando was singled out and threatened with exorbitant bail.

In the prison for 22 days, Fernando kept a daily record of events while he kept working to organize and cheer up the others, finding ways to bridge language barriers to communicate with Chinese workers and help them with their phone calls, and intervening to assist an African prisoner driven to desperation by incarceration. After his release, on each of the occasions we accompanied him to hearings at immigration court, he ran into people he had met in the migra jail, all of whom greeted him effusively. When the judge finally sentenced him to what is hypocritically called “voluntary departure” (in which the deportee pays his own air fare), Fernando answered that he still had much to do here. Immediately afterwards, on the steps of the courthouse, he sold an Internationalist Group pamphlet to another defendant he had met in jail. He took particular pride in his success at distributing our publications.

As a comrade noted at the memorial meeting for Fernando:

“The government said he was ‘illegal’ because he lacked some little papers called immigration documents. The bourgeoisie thinks it is all-powerful. But it is nothing when faced with the power of the proletariat, and its tribunals and jails will fall to pieces when the workers decide it shall be so and, having acquired consciousness of themselves as a class, take the power in a socialist revolution.”

In systematically investigating the origins of the League for the Fourth International (LFI) in the expulsion of a number of leading cadres from the International Communist League (ICL), he closely studied polemics between the two organizations. As a worker communist and internationalist he expressed bitter revulsion at the ICL’s betrayal of a hard-fought struggle to remove police from the municipal workers union in Brazil, and their degeneration into what he characterized as revolucionarios de escritorio (office-bound revolutionaries). At the same time he was full of optimism for the prospects of genuine Marxism; he was reading avidly about Leon Trotsky’s life and planning to visit and help work at the Trotsky museum in Coyoacán, Mexico, established at the house where the co-leader of the October Revolution – who found himself on the “planet without a visa” – was killed during his final exile.

Comrade Fernando at an organizing meeting in NYC.

As the Liga Quarta-Internacionalista do Brasil, section of the LFI, wrote in a “posthumous tribute to a young revolutionary”:

“Fernando was dynamic and full of life. His struggles and his communist ideals made a profound impression on us, and we believe they are cause for pride for those, such as we of the League for the Fourth International, who knew him and felt the sincere way in which he spoke, lived and fought to put an end to discrimination against immigrants, racism, machismo, homophobia and all forms of bigotry, pointing out that only international proletarian revolution will emancipate humanity from these and all other evils afflicting the exploited and oppressed. Courageously, Fernando raised his fists and gave voice to this call in the very entrails of today’s most powerful capitalist country, the United States of America.”

In remarks in Spanish to the April 13 memorial meeting, composed primarily of immigrant workers, an Internationalist Group spokesman noted:

“For the bosses, as you compañeros are very much aware, the worker is worth less – much less – than a machine. For them, the workers are nothing more than raw material for exploitation. They view the working man and woman, the black person and Latino, the Indian, the white worker or the worker from China, Korea or India, as nothing more than a source of profit.

“For this reason, the bourgeoisie would like the workers to remain obedient, silent, with their backs bent, bodies tired and spirits fatalistic, heads bowed and empty or filled with prejudices, superstitions and dark hatreds against those of other races or nations. For the capitalists, when the workers are not slaving at their machines they should be on their knees before the masters of this world: divided, atomized, deceived and believing themselves to be worthless.

“But Fernando, who questioned everything, did not agree. In you, comrades, in the workers of the garment industry, in the immigrant workers from Latin America, from China, from Africa – like Amadou Diallo – and so many other places; in all the workers and oppressed of this planet, Fernando saw something different, something special.

“Fernando saw in every working man and woman the ability to think with his or her own head, to understand their own situation, that of their class and that of society as a whole; to enter into history, geography and politics – in other words, a limitless potential. He wanted the workers to question, debate and understand, to appropriate for themselves and their children the fruits of civilization and of their own labor. It was thus that through many experiences and battles he reached the conclusion that together the workers can transform this world by taking it into their own hands....

“He had come to the understanding that the international working class has a mission, which is not simply to win a piece of bread which is a little bit bigger, but to emancipate all humanity, all those who labor, all the exploited and oppressed. Fernando was definitely a radical: he wanted to find the root of problems; he wanted to uproot exploitation and create a classless society. Because the proletariat is the class with radical chains, and by breaking them it breaks the chains of all the oppressed of the entire earth. Because of this Fernando was an internationalist; he was a revolutionary, and he became a Marxist, a communist....

“We will always remember him with love, with grief and with joy. It was an honor to have known him, to have fought at his side and to have become his friend and comrade. His ideas and example will always live with us all.” ■