September 2023

A Review of Oppenheimer:

Socialism or Nuclear Armageddon

Oppenheimer director Christopher Nolan stands in front of a screen promoting the film. (Photo: Valerie Macon / AFP)

By Luca and Karla

A crucial moment in Oppenheimer, this summer’s

biggest blockbuster, comes after a long build-up to the

film’s depiction of “Trinity” – the test of the atomic bomb

developed by J. Robert Oppenheimer’s team of physicists at a

secret military site in Los Alamos, New Mexico. When the

countdown reaches zero at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, the

button is pushed to detonate the “gadget” – and sound stops.

The screen fills with the terrifying sight of the nuclear

blast, flames, flying debris, the mushroom cloud. All this

the viewer experiences in silence. Unbearable seconds seem

to go on forever – and then we’re hit with the deafening

sound of the explosion at the moment an “air blast” of wind

and dust reaches the scientists shown on screen.

What was tested at Trinity was a prototype for the bomb

that three weeks later, on August 6, the United States

dropped on the civilian population of Hiroshima, Japan. On

August 9, the U.S. dropped a second atom bomb, on the

civilian population of Nagasaki. It is estimated that over

200,000 people were killed in the A-bombing of these two

cities, which came after U.S. firebombing of Tokyo

(estimated deaths: almost 100,000) and dozens of others had

been carried out using “conventional” weapons. These

historic crimes, and so many others committed by “our own”

U.S. imperialist rulers, must be burned into the

consciousness of students and youth today.

“Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds,” says J. Robert Oppenheimer in the film (as in real life), quoting a phrase from an ancient Hindu text. We later see him reminding Albert Einstein that at the inception of the Manhattan Project (the government’s highly classified project to build the bomb), “We thought we might create a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world.” “What of it?” Einstein asks. “I believe we did,” says Oppenheimer. An image of nuclear flames consuming the world fills the screen – and the closing credits roll.

Certainly the fear of thermonuclear war – and if people don’t know this danger is escalating fast, they’re not paying attention – is one reason many are flocking to see Oppenheimer. Others seem just to seek a few thrills from the latest widely hyped flick from writer and director Christopher Nolan (Dark Knight, Batman Begins, Interstellar). The cast of Cillian Murphy (playing the title character), Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr. and many others plays its assigned roles to the hilt, and the film definitely makes an impact. What’s being debated widely in the media and elsewhere is just what that impact is.

For young Marxist activists like those of us working to put out this issue of Revolution, and hopefully for readers of our paper, Oppenheimer poses questions and topics of great importance. In a short review like this, we can only touch on some of these, while emphasizing how important it is to learn about these crimes of U.S. capitalism, as part of the fight to overthrow it. Together with books and films such as Hiroshima (1953), The Atomic Cafe (1982) and White Light/Black Rain (2007), resources include articles in this and other issues of Revolution. In an article on NYC’s “Nuclear Preparedness PSA” in our previous issue (Revolution No. 19, September 2022), we noted:

“To this day, American schoolchildren are taught that the U.S. mass murder of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ... was ‘necessary’ to ‘save American lives.’ In reality, the nuclear attacks that killed hundreds of thousands in the blink of an eye were warning shots heralding the imperialist offensive on the Soviet Union we know as the Cold War. (Meanwhile even ... ex-general and president Dwight Eisenhower, who played a key role in expanding U.S. nuclear weaponry, later admitted that the criminal bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had little military significance in the inter-imperialist war with Japan.)”

In Oppenheimer this is reflected, briefly, when Oppenheimer says that Henry Stimson, secretary of state under Harry Truman – the Democratic president who ordered the bombings – “tells me we bombed an enemy that was already defeated.”

In the wake of the film’s release, a number of articles have enumerated top U.S. military leaders from World War Two whose statements directly contradict the official story about why the A-bombs were dropped.1 Chester Nimitz, for example, who was commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific fleet, said: “The use of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan, [which was] already defeated and ready to surrender.” Carter Clarke, a brigadier general who summarized intercepted cables for Truman, said: “When we didn’t need do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it ... we used [Hiroshima and Nagasaki] as an experiment for two atomic bombs.”

First Blast of the Cold War

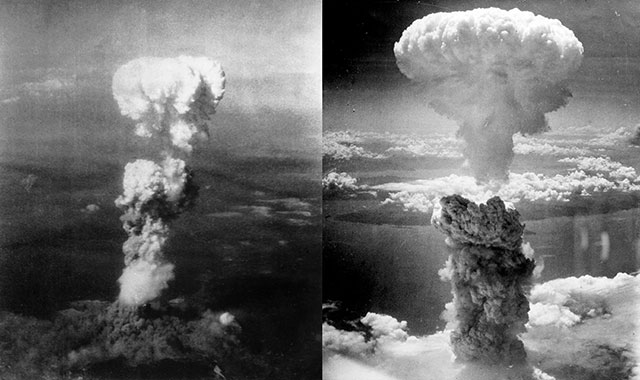

Mushroom clouds over the atom bombing of Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki, August 1945. Memory of these monstrous war crimes by U.S. imperialist rulers must be seared into the consciousness of students and youth, and everyone today. (Photo: U.S. National Archives)

A mountain of research demonstrated, years ago, that Truman and other leaders of U.S. imperialism were certainly avid to test the bomb on large populations in cities that had not “already been destroyed,” in the words of the official Target Committee. Already at the committee’s first meeting, held at the Pentagon on 27 April 1945, the decision was made to target “large urban areas of not less than 3 miles in diameter existing in the larger populated areas.”2

The willingness to use Japanese civilians in this “experiment,” as Truman referred to it, was facilitated by virulent anti-Asian racism. Widespread in the U.S., this was systematically intensified during WWII, both abroad and “at home,” where liberal icon Franklin D. Roosevelt put Japanese Americans in camps.

A key factor in the U.S. decision to bomb Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, was that the Soviet Union was about to declare war on Japan, which it did on August 8. Truman’s “human sacrifice” of the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was in this sense the first blast of the Cold War: a message of terror that U.S. imperialism, intent on world domination, directed against the Soviet Union. This fact was always clear to the Trotskyists, who upheld military defense of the USSR, a bureaucratically degenerated workers state, while opposing the inter-imperialist war of our “own” capitalist rulers in WWII. But not only to us. It was abundantly clear to the Soviets, 27 million of whose citizens died in that war, in which the Red Army defeated Hitler. It was apparent to millions around the world, from the “democratic” Allies’ colonial subjects in Africa, Asia and Latin America, to the huge numbers of communist workers in war-ravaged Europe.

That the atomic bomb was a threat directed against the USSR was stated repeatedly, but of course not publicly, by a range of U.S. officials. Among them: the military head of the Manhattan Project himself, General Leslie Groves. “Groves said that, of course, the real purpose in making the bomb was to subdue the Soviets,” noted Manhattan Project scientist (later a Nobel Prize winner) Joseph Rotblat. Though the USSR was then allied to the U.S., Groves said that since shortly after taking charge of the A-bomb project he was quite aware “that Russia was our enemy, and the Project was conducted on that basis” (Los Alamos Reporter, 19 July).

After 1945, the United States – the only country that has ever used atomic weapons in war – would repeatedly threaten to use them again, and repeatedly come close to doing so over the following decades.3 The Soviet Union’s development of its own nuclear weapons was crucial to staying the hand of U.S. rulers itching to nuke the USSR and China (with “general war plans” that would have resulted in approximately 600 million direct deaths) as well as insurgent colonial peoples from Southeast Asia to the Caribbean.

Aftermath of U.S. atom-bombing of Nagasaki, August 1945. (Photo: U.S. National Archives)

As moving as Oppenheimer's' explosive scene about the Trinity test is, this is about as far as the film goes when depicting the effects of real-life nuclear bombs. One of the controversies swirling around Nolan’s movie is that throughout its three-hour length, the viewer is never shown any images of the death and devastation wrought by U.S. bombs in Hiroshima or Nagasaki.4 Thus the history is seen from the subjective perspective of the “father” of the “gadget” (as Oppenheimer dubbed the A-bomb) rather than the reality of the mass murder and destruction that it caused. Nor is there a glimpse of the effects the bomb tests (and uranium mining for nuclear weapons) would have on Native American, Hispano and other people in New Mexico.5

Obviously this was a conscious choice by the writer and director, who follows the protagonist-eye-view conventions of many biopics. While beset by “qualms” and unnerved by the subsequent drive to build the hydrogen bomb – a thousand times more powerful than the A-bomb – Oppenheimer continued (in the film and in real life) to defend the decision to bomb Hiroshima for the rest of his life. Some argue that the film’s omission of scenes of the bombing is intended to evoke Oppenheimer’s desire to “look away” from the results of his Project. We watch him trying to do just that at one point, as images (that we do not see) of Hiroshima’s devastation are projected on a screen at a meeting he attends. Earlier, amidst a flag-waving celebration at Los Alamos after the news of the bombing arrives, he hallucinates vague faces disintegrating. Outside the cheering, foot-stomping conclave, one young scientist vomits into the bushes.

Other reviewers have argued that Nolan’s decision not to show images from the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is some subtle incitement for viewers to go out and find them on their own. For our part, we hope those questioning the social set-up served by U.S. imperialism’s masters of war will be impelled, after watching the film, to dig deeper. The “values” of this social system were on display yet again when Warner Brothers’ “social media engagement” involved hyping the film via “Barbenheimer” mashups making light of the atomic bomb. Facing an outcry in Japan that might affect ticket sales, the company “apologized.”

Witch Hunt Paradox?

From the beginning of Oppenheimer, a central theme is the anti-communist witch hunt that took off in the postwar United States. Kicked off by Democrats and personified by Republican senator Joseph McCarthy, the Cold War purge led to thousands of people losing their jobs and passports, being blacklisted (such as the “Hollywood Ten,” as shown in the 2015 film Trumbo), censored and jailed. The red hunt reached a deadly frenzy as the capitalist state used Sing Sing prison’s electric chair to murder Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1953 on charges of passing the Soviet Union information on the atomic bomb. (See “Honor the Heroic Rosenbergs,” The Internationalist No. 18, May-June 2004.)

It might seem a paradox that the father of Washington’s pride-and-joy weapon would be a witch hunt target, but it was a sign of the times. The film dedicates most of its last hour to closed-door interrogations, backroom scheming and public hearings against Oppenheimer. These led, in 1954, to the Atomic Energy Commission revoking the security clearance that he had held since ’42, due to associations “beyond the tolerable limits” with “persons known to be” Communists. In part this was because, after the war, he began urging the U.S. government to replace “coercion” with “persuasion” in its foreign policy. He also fell afoul of H-bomb enthusiasts such as Edward Teller, sometimes known as “the real Dr. Strangelove” – a reference to Stanley Kubrick’s hit 1964 film satirizing the U.S. military/nuclear-weapons establishment.

From the beginning of the film, Oppenheimer’s left-wing associations going back to the 1930s generate tension. While he was never a member of the Communist Party, various friends, and family members were or had been; and for some time he backed CP-promoted causes from unionizing lab workers to fund-raising for anti-Franco forces in the Spanish Civil War. By this time the party had moved far away from its revolutionary origins. The “popular front” politics of class collaboration, which Stalin imposed as a corollary of his anti-revolutionary dogma of “socialism in one country,” made the Stalinized CPUSA the most energetic booster of FDR. During the Second World War, it demanded that unions adhere to the “no-strike pact” – and grotesquely hailed the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima.

At one point, Oppenheimer shows its protagonist responding to the red scare’s disruption of his career by declaring: “I’m a New Deal Democrat!” This was true. And clearly for the film’s director, as for so many liberals then and now, the problem with the red scare was that it wound up unfairly besmirching those “innocent” of actually being communists. Which is what we Trotskyists are – revolutionaries who seek to take the red flag of Lenin and Trotsky to victory here and around the world.

Revolutionary Internationalist Youth and Internationalist Group march through New York’s Grand Central Terminal, May Day 2023. “Only Socialist Revolution Can Stop World War III.” (Photo: Valerie Macon / AFP)

Washington’s supposed desire for “peace” (sic) was, after all, part of the sales pitch for the U.S. using the bomb in the first place. An end to nuclear terror can’t come through pacifist pleas to the imperialists to “come to their senses” and “learn to get along” with the rest of humanity. They can’t: imperialism is not a “bad policy” but the highest stage of capitalism, which long ago became a reactionary system. It has to be overthrown by the workers of the world, before it actually does turn the world into a ball of thermonuclear fire.

“I am become death, destroyer of worlds” – if we listen, we can we hear capitalism itself speaking to us in these words. It is up to us to stop it and to “bring to birth a new world” – a socialist world – fit for all humanity. ■

- 1. See, for example, article quoting “WWII’s US Top Brass,” Consortium News, 9 August.

- 2. “Notes on Initial Meeting of Target Committee,” declassified in 1975 and reproduced online at National Security Archive site, nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB162/4.pdf

- 3. See “Mad Bombers on the Loose (in the White House),” Revolution No. 19, September 2022.

- 4. The film closely follows the biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2006), by Kai Bird, an editor and columnist for the liberal Nation, and Martin J. Sherwin.

- 5. The term Hispano is traditionally used in New Mexico by descendants of the Spanish-speaking population that was conquered by the U.S. in the Mexican-American War (1846-48).