October 2020

For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution!

Slavery and the Constitution:

Origins of U.S. Capitalist “Democracy”

By James

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi signs articles of impeachment against Donald Trump, January 15. “#DefendOurDemocracy” became the Democrats’ rallying cry throughout the impeachment fiasco, in which the bigot-in-chief was tried by the wrong class for the wrong crimes. (Sarah Silbiger / UPI)

Long ago and far away – or so it seems these days – in the B.C. era (Before Coronavirus, that is), bourgeois politics in the United States fixated briefly on impeachment. On 18 December 2019, the lower house of Congress – the House of Representatives – voted to impeach Donald Trump. On 5 February 2020, the curtain came down on a farce foretold, as the upper house of Congress – the Senate – voted to acquit him.

As we Marxists noted at the time, the Democrats leading the lower house of Congress did not, of course, impeach Donald Trump for his crimes against the oppressed, for example his “sadistic murderous cruelty against refugees at the border” and “vicious persecution of immigrants in the U.S.” After all, the record deportations under the Democratic administration that paved the way for Trump made Democratic president Barack Obama “deporter-in-chief.” Instead, they staged an electoral gambit accusing Trump of getting in the way of strategic goals of U.S. imperialism by holding up the delivery of weapons of war to a “U.S. ally” (Ukraine), in which the Democrats banked on dissatisfaction with the erratic, “soft-on-Russia” president in the military and intelligence “community.” Trump was “brought up on charges by the wrong class for the wrong crimes,” noted The Internationalist.1

While Democrats charged Trump with obstruction of Congress, his backers pointed to Article II of the U.S. Constitution, claiming that it allows the president to do “whatever he wants.” In fact, the Constitution established a powerful executive, often called the “imperial presidency.” Democrats and Republicans vied to see which party of racist U.S. capitalism could pretend to be more passionate about differing “interpretations of the Constitution.” Both wielded an old political and ideological weapon: what historians call the “civic religion” that has taught one generation after another the mythology of the Constitution as an abstract embodiment of “democracy” in general, an abstract ideal akin to the Ten Commandments to be worshipped alongside the “Founding Fathers,” etc. Yet the creators of the Constitution understood very well that they represented not “the people” in general but the ruling class of planters and merchants, and wrote it to safeguard their interests.

In works like the Communist Manifesto (Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, 1847) and State and Revolution (V.I. Lenin, 1917) – crucial reading for all who want to do away with capitalist oppression – the founders of our movement explained that “bourgeois democracy” was a step forward compared with monarchies and the feudal aristocracy. Today, against attacks on basic democratic rights ramped up by Democrats and Republicans in this country, Marxists are the most intransigent defenders of those rights, which were won by mass struggle. Some of them were codified in the Bill of Rights; the smashing of chattel slavery in the Civil War resulted in a number of key amendments, and women’s suffrage was finally established through the 19th Amendment.

Bourgeois democracy is a form of government administering the capitalist state. Quoting Engels, Lenin emphasized that the core of that state consists of the “armed bodies of men” (police, armed forces, etc.) whose function is to uphold the power and property of the ruling class – that is, to enforce the class dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. In “normal” times, the democratic republic is “the best possible political shell for capitalism,” in which capital “establishes its power so securely, so firmly, that no change of persons, institutions or parties in the bourgeois-democratic republic can shake it” (State and Revolution).

But when the capitalists consider their rule to be threatened, they can sweep away all trappings of democracy, constitutions, parliaments and the rest. One only has to look at how the “democratic” German government turned power over to Hitler in 1933, or how the Chilean bourgeoisie had the “constitutionalist” army head Augusto Pinochet carry out a bloody coup in 1973 to establish the military dictatorship that ruled with an iron fist for 17 years.

Looking at the particular set-up of capitalist rule in the United States, the fact is that the U.S. Constitution set up a particularly anti-democratic institutional framework. By way of comparison, in many parliamentary systems the government can fall through a no-confidence vote by the majority of elected representatives, which would be followed by new elections. In Britain, for example, votes of no confidence have brought down 21 prime ministers since the office was established in 1742, must recently in 1979.

Abolitionists Said Constitution Was a “Covenant with Death”

Written when “We the People” meant that black people, Native Americans, women, as well as many white poor and working people were openly excluded from “democracy,” the United States Constitution still established a series of major barriers to the exercise of the vaunted “will of the people.” Taught in civics classes as the embodiment of impartial “checks and balances,” they were in fact designed, and explicitly motivated by the Constitution’s “Framers,” to protect property and wealth against the masses. Above all, key institutions were established to bolster and uphold the power of the slaveowners in the newly established American republic.

Slavery shaped the Constitution so flagrantly that William Lloyd Garrison, a pioneer of the abolitionist movement, called it a “covenant with death” and “an agreement with Hell.”2 One of the best-known abolitionist polemics was The Constitution A Pro-Slavery Compact (“compact” meaning deal in the language of the day), by Wendell Phillips. Published in 1844, it called the Constitution “that ‘compromise’ ... granting to the slaveholder distinct privileges and protection for his slave property, in return for certain commercial concessions upon his part toward the North.” Phillips denounced “our fathers” (aka the Founding Fathers) for having “bartered honesty for gain,” with a Constitution that embodied the Northern elite being “partners” with the slaveholders, to “share in the profits of their tyranny.”

This is a key reason why the U.S. Constitution established a series of institutions that are strikingly anti-democratic. They remained so even after slavery’s abolition through the Civil War and a number of modifications over the years. The same governmental framework for administering the bourgeois state – a machine of organized violence against the oppressed – continued to bolster the capitalist rulers’ power.

Of, By and For Whom?

Generations have had a lot of patriotic pablum pounded into their heads about the figures who, supposedly guided by selfless devotion to abstract principles, wrote the nation’s charter at the Constitutional Convention, held in Philadelphia back in 1787. A good antidote is to look at how institutions enshrined in the Constitution reflect the real class forces and material interests involved.

- The presidency. This crowns the structure largely built to the slave owners’ measure. “For 32 of the Constitution’s first 36 years,” a “slaveholding Virginian occupied the presidency.”3 And for 50 of the 72 years up to 1860, slave owners held the office, and openly pro-slavery Northerners such as James Buchanan (known as “doughfaces”) did so the rest of the time.

The framers of the Constitution knew it wasn’t feasible to have a king, though Alexander Hamilton wanted the president to serve for life. They settled for establishing an executive branch headed by a president, to whom the Constitution gave extraordinary power. Today, that includes the power to blow up the world. The president can presently be elected to up to two four-year terms and is virtually impossible to remove from office.

- The Electoral College. This was established to help ensure the election of a president with what Hamilton called the “requisite qualifications,” that is, acceptable to the ruling class. In particular, though, the Electoral College boosted the power of the Southern states based centrally on slave labor. This is because the number of electoral votes assigned to each state is determined by that state’s “whole Number of Senators and Representatives,” which included slaves under the infamous 3/5ths Clause, until slavery was finally abolished through the Civil War.

In the 1800 elections, for example, “without the votes of the extra electors that resulted from the addition of three-fifths of the South’s slaves to the population calculation,” Thomas Jefferson would not have won the presidency.4 Jefferson, who sought to extend the Southern slaveocracy’s power to the Caribbean and beyond, was particularly alarmed by the Haitian Revolution. “If this combustion can be introduced among us ... we have to fear it,” he wrote James Madison, warning against allowing news of Haitian slaves’ heroic uprising to reach the slave states of the U.S. As president, he sought to work with the European powers to seal off and strangle the black republic. Vastly expanding U.S. territory – and with it the land for slave plantations – through the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson later wrote to James Monroe (author of the Monroe Doctrine of U.S. dominance of the Western Hemisphere) with the proposal to annex Cuba, where the sugar industry was coining enormous wealth from slave labor.

- The Supreme Court, made up of nine black-robed dispensers of ruling-class “justice” appointed for life by the president. (The president also appoints many other federal officials, who often remain in office for decades.) Up until the Civil War, the Southern slavocracy essentially controlled the Supreme Court. For the vast majority of the antebellum period, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was a Southern slaveowner, and over half of justices throughout that 72-year period also owned slaves. Southern planter domination of the Supreme Court resulted in verdicts such as the Dred Scott decision, which ruled that residence in a free state or territory did not entitle an enslaved person to their freedom – with chief justice Roger Taney stating that black men had “no rights which the white man is bound to respect.”

Toussaint Louverture, leader

of the Haitian Revolution, which terrified U.S. slaveholders. (from John Carter Brown Library)

Toussaint Louverture, leader

of the Haitian Revolution, which terrified U.S. slaveholders. (from John Carter Brown Library)By Constitutional design, the Supreme Court can stymie legislative changes; and it can roll back decisions like Roe v. Wade, which at least finally recognized women’s basic democratic right to abortion, under the impact of mass antiwar, black freedom and women’s rights struggles – and, above all, the victorious Vietnamese insurgents’ fight against U.S. imperialism. Yet the anti-democratic set-up of U.S. “democracy” means Roe v. Wade will never be safe from repeated attacks (and over the years the Democrats helped reduce abortion rights time and again). There is no possibility of democratic recall of justices or any form of popular accountability. Liberal fascination with the Supreme Court centers on waiting for one of its members to die or retire and pushing for more liberal judges, but Marxists understand that the entire institution was formed as one more means to prevent the population from having “too much” exercise of democratic rights. As the Trotskyist press noted in 1936:

“That the Supreme Court is but one of a host of instrumentalities and principles embodied in the Constitution by its makers to thwart forever the possibility of majority rule; that the Founding Fathers had as their fundamental aim the erection of such permanent barriers; that the hostility to majority rule is, in fact, the very essence of the Constitution – such ideas are repugnant to the ruling class, which prefers to perpetuate the myth that the Constitution is a democratic document.”5

- The Senate, the upper house of Congress, with two senators per state regardless of how big or small each state’s population is. Originally elected by state legislatures, not directly by voters, the Senate was established as a way of making extra-sure that the House of Representatives, elected on the basis of population, would not enact measures unpalatable to wealthy property owners. After all, Madison, the Virginia slave owner who wrote the first drafts of the Constitution and co-wrote the Federalist Papers, said the rights of property must be protected “against majority factions.” Virginia governor and slave owner Edmund Randolph warned the Constitutional Convention against “the turbulence and follies of democracy,” and advocated a “good Senate” to “restrain, if possible, [democracy’s] fury.” John Dickinson of Delaware, a slave owner and signer of the Constitution, said senators should be “distinguished for their rank in life and their weight of property.” No wonder the U.S. Senate came to be known as a “millionaires’ club.”

Securing “Monied Interests”

Northern framers of the Constitution had reasons of their own for backing the establishment of the Senate, with Eldridge Garry of Massachusetts highlighting the need for making “the commercial & monied interest ... secure.” Roger Sherman of Connecticut, who signed the Declaration of Independence as well as the Constitution, said the people “should have as little to do as may be about the Government.” Hamilton, one of the most far-seeing representatives of that “interest” in the North, warned his fellow Founding Fathers not to “incline too much to democracy.” Their drive for a new Constitution was partly fueled by fear of unrest among small farmers like those had who launched Shays’ Rebellion in western Massachusetts in 1786-87. Angry about poverty, foreclosures and new taxes, the rebels, many of them Revolutionary War veterans, attacked courthouses and government offices, demanding debt relief and stopping judges from holding court.

Massachusetts’ Henry Knox, a military commander during the Revolution and the future first Secretary of War, wrote George Washington in October 1786 about the rebellious farmers:

“They see the weakness of Government[,] they feel at once their own poverty compared with the opulent, and their own force, and they are determined to make use of the latter in order to remedy the former. Their creed is that the property of the United States has been protected from the confiscations of Britain by the joint exertions of all, and therefore ought to be the common property of all.… Our government must be braced, changed, or altered to secure our lives and property.”

This and similar rebellions alerted the Northern elite to the need, from their standpoint, for a more centralized government with much broader executive powers. This meant scrapping the Articles of Confederation, under which the U.S. operated from 1781 to 1789, and replacing it with a new Constitution. One of their complaints was that unicameral legislatures in the states had shown too much “weakness” toward the poor farmers, and they saw a strong national Senate, made up of men of property, as part of the “remedy” to such dangers.

The origin and nature of the Senate is connected to the ludicrously undemocratic nature of the impeachment process. A president is “impeached” when the House of Representatives brings articles of impeachment against them. But it takes a two-thirds majority of the Senate to convict and remove a president. This has occurred exactly zero times. Though the House of Representatives has voted in favor of impeachment on three separate occasions in U.S. history, the Senate has rejected the impeachment, voting to acquit the sitting president, every time.

The origins of the impeachment process date back to 14th-century England, where aristocrats were tried by their peers, i.e., other nobles. As the liberal New Yorker magazine noted last October:

“The House of Commons couldn’t attack the King directly because of the fiction that the King was infallible (‘perfect,’ as Donald Trump would say), so, beginning in 1376, they impeached his favorites, accusing Lord William Latimer and Richard Lyons of acting ‘falsely in order to have advantages for their own use.’ Latimer, a peer, insisted that he be tried by his peers – that is, by the House of Lords, not the House of Commons – and it was his peers who convicted him and sent him to prison. That’s why, today, the House [of Representatives] is preparing articles of impeachment against Trump, acting as his accusers, but it is the Senate that will judge his innocence or his guilt.6

Capitalism and Slavery

Capitalism and Freedom, a paean to the profit system by right-wing economist Milton Friedman, has been admired by apologists for “free-market” exploitation since its publication in 1962.7 Its title was doubtless intended, in part, as a riposte to Capitalism and Slavery (1944), a key historical work by Trinidadian leftist Eric Williams. In fact, as Karl Marx explained, the slave trade and the system of chattel slavery played a crucial role in the onset of the capitalist era, as well as in the growth of capitalist economy internationally and in the United States specifically.

Together with his incisive analysis of the U.S. Civil War, Marx’s writings on these topics are highly relevant today for understanding the roots of racist oppression and the historical forces that shaped the society we live in. In recent years, since the 2008 depression led to growing interest in critiques of the capitalist system, leftist historians have published a number of studies further detailing just how central Southern slavery was to the rise and development of U.S. capitalism as a whole, including wealth and fortunes accumulated in the North.8

It was indeed “profits,” as Wendell Phillips noted back in 1844, that underlay the alliance between Northern and Southern propertied elites that gave birth to the U.S. Constitution. Both groups had come to see their interest in breaking loose from Britain in the late 1700s. Both resented new taxes levied by London. Northern merchant and commercial sectors were held back by laws forcing them to sell their goods in Britain; Southern planters like George Washington and Patrick Henry were angry at Britain for restraining westward expansion of slave plantations after the “French and Indian” War, and at their growing debts to British merchant houses.

Seeing a colony establish independence from the “mother country” and reject monarchy – which for centuries had claimed a divine right to rule – stirred hopes among many around the world inspired by Enlightenment ideals and fed up with the old order. But what America’s “Founding Fathers” sought and carried out from 1776 to 1783 (when the British conceded defeat) was a political separation from Britain, so the American propertied elites could rule the roost. Unlike the French and Haitian revolutions it helped touch off, the American Revolution was not a social revolution – and Marxists do not celebrate the Fourth of July. Instead, we recall Frederick Douglass’ 1852 speech, “What, to the Slave, Is the Fourth of July?”9 As for the national anthem, it is a star-spangled paean to racist oppression, threatening “the hireling and slave” with “the doom of the grave.”10

Though the founding elites had to use plebeian sectors to defeat the British, their own needs and outlook marked the new republic’s set-up. While the American Revolution gave an impetus to end slavery in the Northern states (by 1804, all of them had decreed its abolition), it was followed by a vast expansion of slavery for the Southern plantation owners, whose domains grew ever larger as the U.S. pushed westward through the Louisiana Purchase, “removal” and genocide against Native Americans, the acquisition of the Oregon Territory through threats of war against Britain, the creation of the Texas slave state, and then the Mexican-American War (1846-48).

In a series of letters published in a Viennese newspaper at the beginning of the Civil War, Karl Marx explained the economic and political logic of the slave system’s expansionism. Though there isn’t space to go through his points here, we would highly recommend the summary of them that is part of an in-depth article marking the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, in The Internationalist (No. 34, March-April 2013).11 One key aspect was that the slave system’s production of cotton and other export crops was threatened due to soil depletion. As the article notes, “The slavocracy’s profits in [key] states were coming more and more from slave raising and the provision of slaves to other slave states. The market for slaves in the other states was limited, and so the expansion of slavery into other areas where extensive cultivation could be undertaken was imperative.” Additionally, the advance of Northern industry and population threatened to reduce the political advantages the Constitution had given the South. The slaveholders needed more slave states to maintain their political power in Washington.

The Second American Revolution

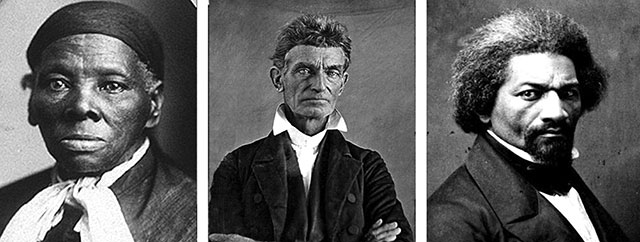

Heroic fighters for the abolition of slavery: Harriet Tubman, John Brown and Frederick Douglass.

(Photos: Smithsonian Institution; Boston Athenaeum; New York Historical Society

As the U.S. expanded westward, the balance of power between the Southern slavocracy and the Northern merchants and manufacturers kept threatening to blow up. One “compromise” after another was made and then broke down. Already in 1820, leaders of the two “sections” of the U.S. put together the Missouri Compromise, stipulating that slave states and free states would be admitted to the Union in pairs. After Mexico’s abolition decree (1829) led slaveholders like Samuel Houston and Stephen Austin to carve Texas out of Mexico and bring it into the U.S., the White House staged a “border incident” to launch war on Mexico and seize half its territory. With the further expansion that resulted from this war for expanding slavery, Northern and Southern politicians worked out the Compromise of 1850. The new Fugitive Slave Act it entailed was even more vicious that the one Congress had passed in 1793. 1850 also saw the infamous Dred Scott decision.

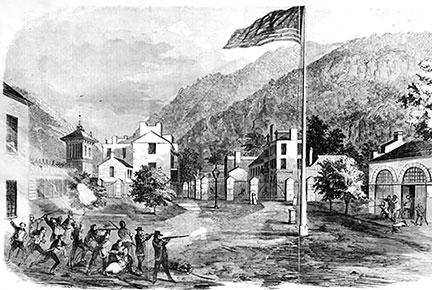

Four years later, the Kansas-Nebraska Act led to armed clashes, most famously in Kansas, where slavers and abolitionists poured into the state to sway the referendum on slavery. Heroic abolitionists like John Brown fought to blaze a path toward the destruction of slavery during the battles of “Bleeding Kansas” in 1856. In 1859, leading a heroic force of black and white fighters in an attack on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, in hopes of touching off a slave revolt across the South, Brown was captured by troops under the command of Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stuart. On the day of his execution, Brown declared himself “quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

Illustration of John Brown’s

raid on Harpers Ferry, prelude to the Civil War, which

Marxists also call the Second American Revolution. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated

Newspaper)

Illustration of John Brown’s

raid on Harpers Ferry, prelude to the Civil War, which

Marxists also call the Second American Revolution. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated

Newspaper)After the election of Abraham Lincoln (on a program not of abolishing slavery but of preventing its further extension), the master class of the South launched the Civil War in 1861 with the bombardment of Fort Sumter. The forces of their “Confederacy” would be commanded by the same Lee, Stuart, et al., some of whose vile statues are finally being torn down today. Like Frederick Douglass and other radical abolitionists in the U.S., Karl Marx – then writing from London – understood that the Union could not win the war without tearing out the root of the conflict: slavery. With other leaders of the “First International” (the International Working Men’s Association) and trade unionists, he helped organize workers in Britain to stop moves by the government there to aid the South. In a famous address by the International to Lincoln in November 1864, Marx wrote:

“The working classes of Europe understood at once, even before the fanatic partisanship of the upper classes for the Confederate gentry had given its dismal warning, that the slaveholders’ rebellion was to sound the tocsin for a general holy crusade of property against labor, and that for the men of labor, with their hopes for the future, even their past conquests were at stake in that tremendous conflict on the other side of the Atlantic.”

After one defeat after another for Union armies, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January 1863, freeing three million slaves (though not yet abolishing slavery throughout the U.S.). When black combatants were finally allowed to fight in the war, and almost 200,000 served under arms, this was crucial in the Second American Revolution that defeated the slaveholders’ rebellion and smashed the system of chattel slavery.

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution (1865) formally abolished slavery throughout the U.S. It was followed by two other amendments key to the postwar Reconstruction period: the 14th (1868, giving citizenship to all those born in the U.S.) and the 15th (1870, giving black men the right to vote). However, the former slaves’ call for “forty acres and a mule” – which would have meant seizing and dividing up the plantations – was not realized, particularly after the Paris Commune of 1871, in which French workers briefly took power, heightened Northern capitalists’ fears of a general “assault on property.”

Reconstruction’s promise of black freedom was broken and sold out, a betrayal sealed by yet another “compromise” between the men of property and power in both North and South. This was the Compromise of 1877 between the former slaveholders’ Democratic Party and the Republican Party that increasingly represented the interests of Northern industrialists. As noted in “The Emancipation Proclamation: Promise and Betrayal”:

“The promise of black freedom was thus betrayed by the Northern bourgeoisie, which sacrificed Reconstruction on the altar of profit and ‘national reconciliation.’ The counterrevolution against Radical Reconstruction was then justified in national myth: the cause of thorough-going emancipation and racial equality was buried under layers of lies so thick that generations of schoolchildren were taught – by liberal and rightist historians alike – that Reconstruction had been a terrible mistake, and even that slavery was not the underlying issue of the Civil War.

“The need to fight for black liberation through socialist revolution is highlighted by the fact that the betrayal of Reconstruction meant that the Southern rulers could not only rewrite the story to suit their interests, but roll back a large part of what Reconstruction had achieved, as they pushed social relations as far back as possible towards slavery-like conditions.”

For Socialist Revolution and Proletarian Democracy

Democratic (Party) “socialists” and reformists of various descriptions are forever serving up new variants of the old illusions in bourgeois democracy (“participatory democracy,” “people’s budgeting,” “radical democracy,” etc.) But a basic understanding that every capitalist state exists to uphold the interests of the ruling class, and a look at the specific governmental forms through which the bourgeois state is administered in the U.S., highlight Marx’s point that the working class cannot “lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes.”

Revolutionaries explain the need for a revolutionary workers party to lead a socialist revolution to overthrow the entire capitalist system. This means establishing a workers state (what Marx called the dictatorship of the proletariat). Based on the experience of the Paris Commune and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution led by Lenin and Trotsky, we advocate that the proletarian democracy of a workers state rest on workers councils. These were the “soviets” that took power in Russia (before capitalist encirclement and invasion by over a dozen countries, including the U.S. under ultra-racist Democrat Woodrow Wilson, led to the degeneration of the Soviet workers state and the rise of Stalin’s conservative bureaucracy).

The U.S. Constitution was created to represent the interests of the American ruling class, whose interests have always been opposed to those of the workers and oppressed. For this vast majority, workers rule will be a thousand times more democratic than any capitalist state. Yet as Marx and Lenin argued, international socialist revolution will lay the basis for a classless and stateless society: socialism. With the use of technology and the productive forces providing plenty for all while radically cutting time needed for labor, this will pave the way for communism. Curious about outlived class societies of the past, future students will doubtless learn many things about the final phase of capitalist barbarity when they study the reactionary U.S. Constitution in museums of capitalist antiquities. ■

- 1. “Against Trump and the Democrats – Build a Workers Party. Impeachment Crisis: ‘Deep State’ vs. Bigot-in-Chief, ” The Internationalist No. 57, September-October 2019.

- 2. See “Garrison’s Constitution: The Covenant with Death and How It Was Made,” Prologue, Winter 2000. After a close association with Garrison, the great radical abolitionist Frederick Douglass broke with him; disagreement with Garrison’s adherence to pacifistic “moral suasion” came to a head when Douglass hailed the raid on Harpers Ferry that John Brown launched in October 1859 in an effort to spark a slave insurrection in the South.

- 3. “The Troubling Reason the Electoral College Exists,” Time, 26 November 2018.

- 4. Eric Foner, “The Corrupt Bargain,” London Review of Books, 21 May. Since the workings of the Electoral College gave the 2000 election to George W. Bush and the 2016 one to Donald Trump, despite both losing the popular vote, today Democratic liberals are unhappy with it, while continuing to portray the Constitution as virtual holy writ and the structure it set up as the incarnation of ‘democracy.”

- 5. Felix Morrow, “The Spirit of the U.S. Constitution,” New International, February 1936. This was written in the midst of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, when the Communist Party joined mainstream Democrats in pushing liberal myths and legends about the Constitution, Washington, Jefferson, etc. Its formerly revolutionary politics destroyed by Stalinism, the CP was promoting the “popular front” line of support to FDR, even proclaiming that “Communism is 20th-Century Americanism.” Today, Democratic (Party) “socialists” like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have made a specialty of red-white-and-blue appeals to the tradition of FDR, the New Deal, etc. ad nauseam.

- 6. “The Invention – and Reinvention – of Impeachment,” The New Yorker, 21 Oct. 2019.

- 7. After a U.S.-backed junta seized power in Chile in 1975, overthrowing the elected government of Salvador Allende, crushing unions and murdering thousands of leftist workers and youth, Friedman got a chance to put his idea of “freedom” into practice, devising the starvation “shock treatment” economic plan for military dictator Augusto Pinochet.

- 8. Historian Sven Beckert gives a good description of recent research in “Slavery and Capitalism,” The Chonicle of Higher Education, 12 December 2014. For Karl Marx’s crucial analysis, see the Internationalist pamphlet Marx on Slavery and the U.S. Civil War (2009).

- 9.

You can hear the great black leftist actor Ossie Davis

read it here.

- 10. See “Kaepernick Protest Inspires Youth Defying Racist Repression,” Revolution No. 13, November 2016.

- 11.

See “The

Emancipation Proclamation: Promise and Betrayal,” The

Internationalist No. 34, March-April 2013.