October 2025

Capitalism and Slavery in

NYC: A Review of The Kidnapping Club

Wall Street’s Slave Catchers and the Fight for Black Freedom

By Jacob

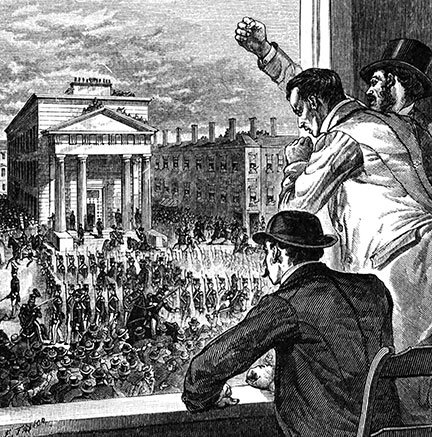

In compliance

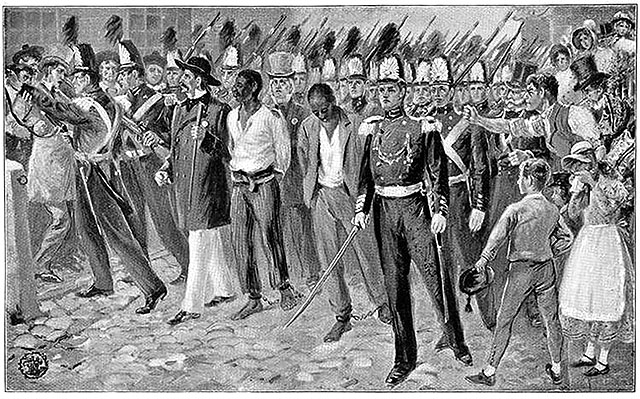

with the Fugitive Slave Act, in June 1854 Anthony Burns was

ordered to be returned to slavery in Virginia. 50,000

protesters lined the streets of Boston as soldiers took him

to the waterfront. In the window and on top of nearby

buildings, people shouted “Kidnappers!”

In compliance

with the Fugitive Slave Act, in June 1854 Anthony Burns was

ordered to be returned to slavery in Virginia. 50,000

protesters lined the streets of Boston as soldiers took him

to the waterfront. In the window and on top of nearby

buildings, people shouted “Kidnappers!” (Photo: Granger Collection)

Today, as masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents conduct raids across the United States, kidnapping people and taking them away in unmarked cars, one can hear the echoes of the slave catchers who in the decades before the Civil War prowled through the streets and alleyways of New York City. Agents of I.C.E., the Border Patrol and other federal agencies lurk outside courtrooms where they tear immigrants away from their families. Recalling the bounty hunters that chased down runaway slaves, newly enrolled I.C.E. agents can get a signing bonus of up to $50,000. In the United States of 2025, undocumented immigrants are a millions-strong labor force crucial to the capitalist economy but deprived of basic rights, a condition enforced by police-state terror that evokes slavery days in antebellum America.

Below immigration courts in downtown Manhattan where harrowing abductions transpire daily lies New York’s African Burial Ground, discovered in 1991 when construction was underway for a new Federal Building at 290 Broadway. Thousands of bodies were buried there in the late 17th and 18th centuries, after enslaved Africans were banned from the city’s public burial ground. Though 160 years have passed since chattel slavery was abolished, the bedrock racism of American capitalism continues to underlie the inequalities of the present. This is the legacy of 1877’s “compromise” between the Democratic and Republican parties that still rule the U.S. today, in which the representatives of Northern capital agreed to Southern ex-slaveowners’ demand to end post-Civil War Reconstruction, betraying the war’s promise of black freedom.1

Manhattan financiers were among those who most strongly opposed measures favoring the masses of former slaves in the South. Echoing the Confederate sympathies many had voiced during the Civil War, they mainly cheered the end of Reconstruction, having long feared that slavery’s abolition, and demands for distributing ex-slaveholders’ land to those they had enslaved, could lead to further inroads on capitalist property. Those fears had been heightened by the Paris Commune of 1871, in which the workers of France’s capital seized power before their revolution was drowned in blood at the end of May 1871. Less than a month later, a Southern correspondent for the New York Tribune (21 June 1871) wrote that “many thoughtful men are apprehensive” that poor whites and former slaves “might form a party by themselves as dangerous to the interests of society as the Communists of France.”

The

Kidnapping Club (2020) tells a true story about

capitalism’s history and about struggles against racist

repression – a story highly relevant to those we face today.

The

Kidnapping Club (2020) tells a true story about

capitalism’s history and about struggles against racist

repression – a story highly relevant to those we face today.

Close connections between New York’s ruling circles and the Southern slavocracy had actually been central to the city’s economics and politics going back long before the Civil War. This theme, which is highly relevant for Revolution readers amidst today’s struggles against racist repression, is brought to life in The Kidnapping Club: Wall Street, Slavery, and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War (2020), an important and engaging book by historian Jonathan David Wells.

Unearthing the connections that ran from Wall Street bankers to Tammany Hall (the notoriously corrupt Democratic fraternal society that ran NYC), to the cops that worked hand in glove with Southern slave catchers and sold free black New Yorkers into slavery, The Kidnapping Club tells a true story that is largely unknown but closely linked to the reality we’re living today. At a time when references to the history of slavery are being “scrubbed” from innumerable public places, textbooks and websites – and efforts are afoot to stop the teaching of that history – knowing the truth about it is all the more important.

“Capitalism Is Freedom”?

Generations of Americans have been taught that capitalism means freedom. The claim is most famously advanced in Capitalism and Freedom by “free-market” icon Milton Friedman –who designed the economic “shock treatment” for Chile’s military dictator Augusto Pinochet. First published in 1961, it is pitched today as a veritable classic.

In the world’s still-leading center of finance capital, a few blocks from the African Burial Ground, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) occupies a massive stately building on Wall Street, facing a large statue of the U.S.’ founding slaveowner, George Washington. The exchange’s website proclaims: “The NYSE is capitalism at its best.” As for Wall Street, it is named for the wall that used to be there, which was built by slave labor. On Wall Street between Water and Pearl, about 160 feet from the NYSE, a sign marks the site where, from 1711 to 1762, the precursor of the city council operated New York’s official slave market.

As Wells demonstrates in his book The Kidnapping Club, the capitalist class in New York City, and the North generally, was deeply involved in the business of slavery. New York gained a reputation as the most pro-Southern city in the North, even taking steps to secede from the Union at the outset of the Civil War. Investors, bankers, insurance and shipping companies, customs officials, lawyers and politicians all had a vested interest in plantation slavery and the transatlantic slave trade, including after it was illegalized in 1808. Underlying the rise and expansion of New York City as a major metropolitan center, as Wells emphasizes, were the profits made from slave labor.

The Kidnapping Club also shows the role of New York’s then-nascent police force, its courts, jails and Democratic Party-run political machine in blatantly serving the intertwined interests of Southern slave masters and Wall Street financiers. Upholding their property interests and power, the police continuously trampled the basic rights of the city’s black population. Though Wells is not a Marxist, his book vividly illustrates Friedrich Engels’ definition of the state – highlighted in V.I. Lenin’s State and Revolution (1917 ) – as “special bodies of armed men” enforcing the rule of the owning class against the oppressed.

“The Kidnapping Club” is what New York City’s foremost abolitionist, the black activist and editor David Ruggles (1810-1849), called the cabal of Wall Street businessmen, cops, judges and slavecatchers that he tirelessly exposed in public meetings and the abolitionist press, including his journal The Mirror of Liberty. Born free in Connecticut, Ruggles moved to the city in 1828, a year after slavery officially ended in New York State. After working for a time as a sailor, he opened a grocery store and subsequently an “anti-slavery bookstore.” Ruggles became the prime mover behind the foundation of the New York Committee of Vigilance, an interracial organization dedicated to defending the rights of all black people – from the free black population to runaway slaves and those who were clandestinely kept in servitude in defiance of state laws.

Today, as we fight for full citizenship rights for all immigrants, and for mass mobilizations by the multiracial working class to drive modern-day bounty hunters out of our cities, we have much to learn from David Ruggles’ story, which is the keynote of this book.

A City Built on Slavery

From its beginnings, going back to when it was called New Amsterdam under the Dutch, New York was reliant on enslaved labor. African slaves cleared the forests and swamplands, worked the farms and were the core of the city’s construction labor force. During the 18th century the size of the New York’s slave population was only surpassed by that of New Orleans and Charleston, the South Carolina port that was a major center for commerce, including the transatlantic slave trade.

New York was one of British North America largest slaving ports (i.e., port cities where enslaved people were bought, sold and unloaded from or loaded onto ships). A slave rebellion burned down large parts of the city in 1712, as did a second one in 1741, which reportedly involved black slaves uniting with poor whites and “free people of color” to challenge colonial authorities. During the colonial period, nearby Brooklyn (a separate city before becoming part of NYC at the end of the 19th century) was overrun with slaveholding farms and plantations that cultivated crops needed to feed the island of Manhattan.

Only after the American Revolution did the tide begin to turn against slavery in the North. Unlike the South, which was a “slave society” – in other words, one based centrally on the institution of slavery – the North was what historians of slavery call a “society with slaves” (one in which enslaved labor was one component of the economic system). In 1799 and 1817, New York stated passed laws that gradually phased out slavery, finally terminating the institution in 1827. Among those legally freed that year was future abolitionist Sojourner Truth, who had been enslaved in Hudson Valley for the first 29 years of her life. But while slavery became illegal in New York more than three decades before the Civil War, racism was rampant.

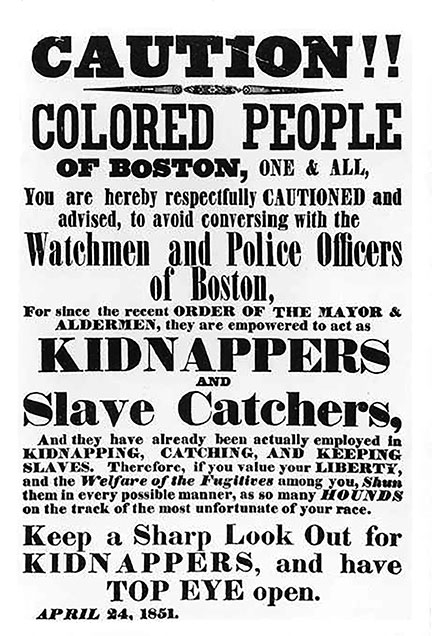

Notice posted

in Boston in 1851 by local abolitionist Theodore Parker.

Notice posted

in Boston in 1851 by local abolitionist Theodore Parker. (Photo: Boston Public Library)

In the 1830s and ’40s, New York’s black population – which reached a peak of 16,300 in 1840 – found itself besieged in a city that, like the U.S. as a whole, was increasingly polarized over the issue of slavery. In 1821, New York State eliminated all property qualifications for white men to vote, but established a $250 property requirement for black men, effectively denying them voting rights. Harassment was a daily occurrence. Transportation was segregated and was customary in restaurants and other public establishments. In the 1840s, a wave of impoverished Irish immigrants arrived and encountered virulent nativist discrimination (portrayed in Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York). Employers pitted Irish laborers against blacks, stoking racist resentment to foment working-class division.

As cotton became the United States’ largest export, New York’s prosperity grew even more dependent on the labor of enslaved black people on Southern plantations. In the years leading up to the Civil War, roughly 40% of U.S. cotton revenue was gleaned by New York City’s financiers, insurance and shipping companies.2 So frequently did slaveholders come to New York on business that a “traveler’s exemption” was created, lasting until 1841, that allowed non-residents to bring their slaves into the state for a period of nine months, making it possible to crisscross state lines to reset the time limit. Moreover, despite the fact that the transatlantic slave trade had been illegalized, it was an open secret that over the following decades New York was a hub in the trade’s illicit continuation in “undercover” form, linking the city’s merchants and shipyards to Brazil, Cuba and the West African coast.

The profits that New York rulers obtained from slavery went a long way. After a fire destroyed much of the city’s financial district in 1835, this wealth allowed the city to replace the ravaged wooden structures that remained with more durable granite buildings; fueled uptown development, leading to expansion of the city limits; and paid for the construction of the Croton aqueduct, ensuring the city a stable supply of clean water. In 1800, New York was a small port city of about 80,000 inhabitants. By 1860, its infrastructure had been transformed and its population surpassed 800,000. Key to this transformation, as Wells demonstrates, were the profits that New York capitalists made from Southern slavery.

Slave Catching in Gotham

Detail from

cover of Harper’s Weekly, 14 January 1882, engraving

by Thomas Nast.

Detail from

cover of Harper’s Weekly, 14 January 1882, engraving

by Thomas Nast. New York’s characteristic hustle and bustle, and the sense of anonymity that grew alongside the city’s population, gave runaway slaves a chance to start life anew as free people. But the same labyrinth of city streets and alleyways also hid the dens of slave catchers. Bounty hunters, lawyers and informants in the employ of Southern slaveowners prowled the North looking to cash in on the kidnapping of black people. By the 1830s, reports of missing black children had become a regular occurrence in New York, but police refused to investigate. A letter from the Anti-Slavery Society pleading to the mayor and aldermen was simply returned without a response.

At any time, black residents of New York could be accused of being fugitive slaves from the South and kidnapped. Southern planters and their agents could strike terror with the sanction of law, while New York’s rulers worked diligently to comply with the demands of their Southern business partners. The original Fugitive Slave Clause, which was part of Article IV of the U.S. Constitution that went into effect in 1788, mandated that enslaved people who escaped to free states could not be granted freedom and “shall be delivered up” upon claim by their owners. In 1793 this was supplemented by the first Fugitive Slave Act, stating that slaveowners and their agents had the legal right to hunt for escaped slaves inside the borders of free states. (As discussed below, a second, even more draconian Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850.)3

Working alongside the slave hunters for hire were New York police, who also got bounties (which they relied on in part to cover legal fees from lawsuits brought by people they had brutalized). In 1832, after Virginia’s governor asked New York governor William Marcy to take action on behalf of an owner of runaway slaves, Marcy gave police a blank warrant to arrest anyone suspected of being a fugitive. Over the following two decades, this particular warrant – which saw so much wear and tear that it had to be copied and re-signed – was brandished by NYC cops Tobias Boudinot and Daniel Nash, who became widely known for their slave-catching activities.

But Boudinot and Nash were far from the only ones. In one notorious case in 1834, a Richmond slave owner and a New York sheriff marched into the African Free School on Duane Street in Manhattan, where they seized a seven-year-old black child named Henry Scott. Henry was dragged before Richard Riker, who served as a judge presiding over the city’s primary criminal court. (He was from the wealthy family that owned Rikers Island and eventually sold it to the city to turn into a jail.) Riker who ordered the terrified and sobbing child to jail while his captor travelled back to Richmond to obtain proof of ownership.

Though Henry managed to obtain his freedom with the help of community support, many others passed from Riker’s kangaroo court into Southern bondage. Nash, Boudinot and other cops and slave catchers would haul captives before Riker’s bench at all hours, reliably obtaining a favorable verdict. Riker would later tell a Southern business agent: “Tell your Southern citizens that we Northern Judges damn the Abolitionists – we are sworn to abide by the Constitution.”

David Ruggles and the Vigilance Committee

As the dominance of “King Cotton” grew in the 1830s and ’40s (by 1840 cotton’s share of U.S. exports reached over 50%), the Manhattan elite’s growing wealth became even more dependent on the business of slavery. After all, as Wells notes, cotton was “a crop financed by Wall Street banks and exported to New England and British textile mills via New York brokers, businesses, and financiers.” And so the influence of Southern slaveholders over NYC’s politics, policing and judicial system grew even greater. African Americans living in New York found that at any moment, they could be stripped of their rights and spirited into Southern bondage.

Against this, the courageous work of abolitionist David Ruggles persistently exposed the actions of the slave-catching and abduction network that he called “the Kidnapping Club.” Together with running New York’s first black bookstore, where he disseminated abolitionist literature, Ruggles was a sales agent and contributor to prominent anti-slavery newspapers, including The Liberator, founded in 1831 by William Lloyd Garrison.4 Ruggles’ polemics (writings against opposing standpoints) included fierce opposition to those who backed schemes for “colonization” of black people with the argument that they could never attain equality in the United States and therefore should migrate to Africa or the Caribbean. Denouncing this, he argued that the U.S. was the home of African Americans and they should organize to claim their birthright to equality.

For his fearless defiance of the Kidnapping Club, exposing the machinations of City Recorder Riker, police officers Boudinot, Nash and many others, Ruggles was frequently the target of retaliation. In the summer of 1834, anti-abolitionist riots rocked New York; Ruggles’ bookstore was burned down and ransacked. He was also the victim of violent attacks by racists objecting to him riding on stagecoaches and train cars. Still, Ruggles continued to push forward the struggle for equality.

Rather than yield to intimidation, Ruggles sought to widen the scope of abolitionist activism in the city. In November 1835, Ruggles established the Committee of Vigilance, which worked to alert the city’s black residents of the presence of slave catchers, to shelter runaways, as well as organizing and funding legal defense efforts. The committee established links with similar groups that were forming in Philadelphia, Boston and other cities, and mobilized its members to City Hall, Riker’s courtroom and the city’s fearsome Bridewell prison in defense of those arrested on charges of being a fugitive. In the course of the ten years following its foundation, according to the committee’s published reports, it saved approximately 1,800 people from the clutches of the Kidnapping Club.

Together with the fight against slave catchers, Ruggles and the Vigilance Committee kept watch for illegal slave trading taking place at the city’s docks. In December 1836, Ruggles got a tip that a known Portuguese slave ship, the Brilliante, had docked in Lower Manhattan. Heading to the docks, he talked with a white sailor who confirmed that the ship carried human cargo and in the port for repairs. Ruggles repeatedly tried to get the New York District Attorney to take action, but got the run-around, followed by a shouted order to get “out of my office!” The case was only taken up after Ruggles got news of it published in two daily papers.

The ship’s captain and the five African men found aboard the Brilliante were then arrested. The U.S. District Court concluded that the five Africans aboard the ship were crew members and released the ship’s captain. Ruggles discovered that the five “crewmen” were being held in a debtors’ prison in City Hall Park at the behest of the ship’s captain until he was ready to depart. Ruggles visited a series of city officials, as well as the prison, trying to secure their release. Each time, he hit a wall – and within a few days the enslaved Africans were returned to the Brilliante.

Retaliation came soon, when the slave-catching cop Daniel Nash, accompanied by a member of the Brilliante’s crew and other men, appeared on Ruggles’ doorstep in the middle of the night with a warrant from the chief of police. Ruggles managed to escape but was later arrested and charged with resisting arrest, but eventually released. The notoriously racist Morning Courier (30 December 1836) lauded Ruggles’ arrest, denouncing his role in the Brilliante case as “one of hundreds of impudent and insolent attempts on the part of the blacks to violate the laws and interfere with the authority of the magistrates.”5

But Ruggles remained undeterred. He continued to track and intervene in cases involving the kidnapping of black people, sometimes traveling across state lines to find leads and advocate on behalf of the victims. He also continued to uncover illegal slaveholding in the New York area; he described Brooklyn in particular as “the Savannah of New York,” referring to the Georgia city known for its major role in the slave trade.6 For this, as Ruggles wrote in the Mirror of Liberty (January 1839), he was denounced as “a nuisance and a vagabond” by the editor of the New York Gazette, one of Wall Street’s many journalistic mouthpieces.

Ruggles faced arrest yet again in the fall of 1838 for aiding in the attempted escape of Thomas Hughes, a young enslaved man whose owner brought him from New Orleans to New York. In a blatant frame-up, police and the Wall Street press tried to pin responsibility on Ruggles for Hughes taking some of the enslaver’s money before fleeing. Abolitionist activists exposed the corruption behind the police investigation and legal proceedings, and Ruggles, after paying a hefty bail, was allowed to go free. As for Thomas Hughes, New York’s capitalist “justice” system declared him “guilty” and sentenced him to two years in Sing Sing prison.

The Split Over Self-Defense

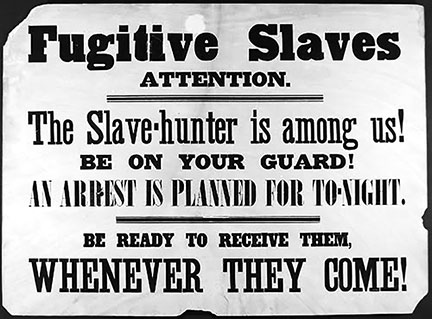

Notices like

this one (undated) were frequently posted to warn fugitive

slaves and those seeking to aid them, when slave catchers

had been sighted.

Notices like

this one (undated) were frequently posted to warn fugitive

slaves and those seeking to aid them, when slave catchers

had been sighted. (Photo: New York Public Library)

As the abolitionist movement grew in the 1830s, so did differences of outlook and strategy within the movement. Its best-known leader at the time, William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), was viewed as an intransigent radical because he called for “no compromise with slavery” and demanded its immediate abolition. At the same time, Garrison and his followers were doctrinaire pacifists, putting forward a strategy of “moral suasion” aimed at persuading the slave owners to give up the sin of slavery.

While Garrison’s Liberator was one of the papers David Ruggles wrote for and distributed, he began to argue for a more militant orientation in the struggle for black freedom. In July 1836, a free black man named George Jones was arrested on Broadway, two blocks from Wall Street, on a charge of battery that served as a pretext for his kidnapping by slave catchers who falsely stated that he was a runaway slave. Reporting on a meeting in Jones’ defense, Ruggles wrote:

“We are all liable; your wives and children are at the mercy of merciless kidnappers. We have no protection in law, because the legislators withhold justice. We must no longer depend on the interposition of Manumission or Anti-Slavery Societies, in the hope of peaceable and just protection; where such outrages are committed, peace and justice cannot dwell… no man is safe; we must look to our own safety and protection from kidnappers; remembering that ‘self-defence is the first law of nature’.”

– “Kidnapping in the City of New York,” The Liberator, 6 August 1836

The differences came to a head during the 1837 defense campaign of William Dixon, a black laborer arrested by Boudinot and Nash and brought to court, presided over once again by Richard Riker. Abolitionist activists and members of the black community in what is now the Lower East Side found a series of witnesses who contradicted the claims against Dixon, , and the case was moved to trial. The Vigilance Committee organized people to observe the trial, helped raise funds for the defense and mobilized hundreds to protest for Dixon’s freedom. Police clashed with demonstrators; some individual activists also attempted to rescue Dixon from his captors.

Samuel Cornish, a Presbyterian minister who edited a newspaper called The Colored American, had been a collaborator of Ruggles on the New York Committee of Vigilance. Both had opposed “colonization” as a defeatist accommodation to racism. Cornish had even abandoned his editorial post at Freedom’s Journal, a paper he had co-founded, over disagreements on this topic. But as slave catching deepened the polarization of New York City and U.S. society at large, the strategic rifts within the abolitionist movement deepened.

As a man of wealth and respectability, Cornish abhorred the protests outside the courthouses and jails and was ill at ease with the militant crowds of working-class black people confronting kidnappers. Denouncing “the ignorant part of our colored citizens,” he expressed particular disapproval with the presence of black women at these actions who, he wrote, “so degraded themselves … we beg their husbands to keep them at home for the time to come, and to find some better occupation for them” (Journal of Commerce, 19 April 1937).

The author of the Kidnapping Club states that “class tensions” within the black community were a big factor underlying the political divisions, as affluent African American leaders often opposed militant protest and organized self-defense. But he misses a key moment of continuity in the struggle. Ruggles’ disagreements with Cornish on self-defense and mass protest came to the fore just as Ruggles was providing shelter for a fugitive slave from Maryland then called Frederick Bailey – who would soon change his name to Frederick Douglass.

Upon arriving in New York, it was at Ruggles’ home at 36 Lispenard Street that Douglass found refuge. (Today, a plaque designates the building as a station on the Underground Railroad.) There he would reunite with the fellow abolitionist Anna Murray and marry her. That Ruggles was a mentor to Douglass and not just a lesser-known predecessor of comparable moral courage goes without mention in The Kidnapping Club. It is likely unintentional that Wells’ book leaves out an important aspect of Ruggles’ legacy in nationwide politics, as the United States hurtled toward civil war over the question of slavery. As Douglass himself recounted:

“I was relieved … by the humane hand of Mr. David Ruggles, whose vigilance, kindness, and perseverance, I shall never forget. I am glad of an opportunity to express, as far as words can, the love and gratitude I bear him…. Though watched and hemmed in on almost every side, he seemed to be more than a match for his enemies.”

– Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

“The Police of New-York on a Slave Hunt”

Opposition to the bounty hunters grew stronger in the 1840s, with increasing numbers of Northerners reacting against the brutal realities of slave catching and the corrupt influence of the Southern slavocracy over Democratic-run politics in New York and other cities. The flagrant arrogance of what came to be called the “Slave Power” (slave owners’ political and economic clout in U.S. society) aroused growing indignation. Yet chattel slavery, so lucrative for so many sectors of the capitalist elite, continued to expand with the annexation of Texas (which had seceded from Mexico in response to that country’s abolition of slavery) and the predatory 1846-48 war through which the U.S. acquired over half of Mexico’s territory.

In New York, 1846 was the year the city was rocked by the case of George Kirk, who had escaped slavery on a Georgia cotton plantation by stowing aboard a ship bound for New York. Discovered by the crew, he was held under lock and key, but when the ship tied up at Manhattan’s wharves, black stevedores (longshoremen) heard Kirk yelling for help. With protesters gathering around the ship, this time it was the captain who was taken to court – where he stated that he intended to return Kirk to slavery. With a large number of black and white slavery opponents in the courtroom, a sympathetic judge ruled in Kirk’s favor and declared him a free man.

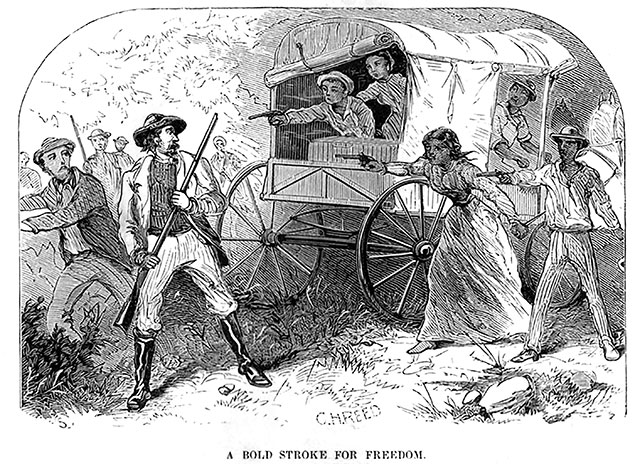

Engraving by C.H. Reed, from The Underground Rail Road by William Still (1872).

But New York’s Mayor Andrew Mickle, a loyal Tammany Hall Democrat who, in Wells’ words was “pressed by Wall Street interests” to intervene in the case, declared there would be a second trial. When another favorable ruling followed, Kirk’s supporters, knowing that city rulers would continue to hound him, rushed him to the Anti-Slavery Society’s office. “The Police of New-York on a Slave Hunt,” headlined the New-York Tribune (30 October 1846); “the whole police force of the city turned slave-catcher” after Mayor Mickle signed a warrant for Kirk’s arrest and sent 900 cops to find him. With massive protests growing, Kirk’s supporters attempted to whisk him away in a crate, but he was ultimately apprehended by the police, who took him to the hideous “Tombs” jail on Centre Street.7 However, the judge set Kirk free again and he soon moved to Boston, where he lived as a free man.

By this time, however, David Ruggles had left New York. The strain of relentless work – together with injuries inflicted on him over the course of his anti-slavery struggle – wore down his health, costing him his eyesight and leading him to move to Massachusetts in 1842. He died there in 1849, at only 39 years of age, and his story was little known for more than a century. We owe a debt of gratitude to the author of The Kidnapping Club for changing that.

Wall Street Hails Fugitive Slave Act – Civil War Approaches

Little more than a decade separated Ruggles’ death from the onset of the Civil War. As had occurred with each prior expansion westwards, the conquest of vast territories from Mexico threw the balance of power in U.S. society into crisis. The composition of the Senate in particular depended on which areas would become slave states and which new states would be based on non-slave labor. The result was yet another of the periodic “compromises” between North and South, the 1850 Compromise.

A key aspect of this was the establishment of an even more draconian Fugitive Slave Act. Its measures included mandating that all escaped slaves be returned to their owners; that citizens of free states collaborate in this directly; that those aiding or harboring fugitives slaves be subject to imprisonment and a steep fine; and that the federal government be responsible for enforcing the act. The Wall Street Journal of Commerce described the act’s approval as “glorious news.” Its editor wrote that no one would be happier to hear this news “than capitalists, whose means are always at a greater risk in troublesome times.” Without the riches deriving from the slave-grown crop, he argued, the United States would fall apart; in the face of conflict, “cotton is the great counteracting element…. Blessed be cotton!” (21 December 1850).8

The first person to be targeted under the new law was New Yorker James Hamlet, a porter who was arrested at his workplace on Water Street in Lower Manhattan. In response to this outrage, Frederick Douglass wrote that “we are all at the mercy of a band of bloodhound commissioners” (Frederick Douglass’ Newspaper, 3 October 1850). While dejection spread among the city’s abolitionists, the Journal of Commerce (28 December 1850) rejoiced that anti-slavery activists “have probably learned rebellion is not so rife in this community as they were taught to believe.”

Despite Wall Street’s hope that slavery’s opponents in Northern cities would resign themselves to the slaveowners’ power, militant resistance broke out in a series of places, including the mass upheaval of May 1854 in Boston. (See box below.) In 1857, outrage intensified still further when the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott stated that nobody of African descent was or could be a citizen of the United States and that Congress could not prohibit slavery in any federal territory. (Dred Scott had sued for his freedom after being taken from Missouri, a slave state, to a free territory.)

In April 1861, the “Confederacy” of secessionist Southern states launched what Karl Marx called the “slaveholders’ rebellion” with the bombing of Fort Sumner in Charleston, South Carolina.9 Today, few people know that under the influence of the city’s capitalist elite – the slaveholders’ Wall Street partners – New York tried to secede from the Union in order to protect the commercial and banking profits fueled by slave-grown cotton. Speaking to the city’s Common Council in January 1861 amidst the secession crisis, the city’s Democratic mayor Fernando Wood expressed “a common sympathy” with “our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States” and proposed that the city withdraw from the Union and declare itself a sovereign city-state. The council voted in favor, but the attack on Fort Sumner aroused the ire of the great majority of New York’s working people, and the secessionist scheme of Wall Street’s mayoral puppet fell through.

Where did the present-day political, social and economic set-up come from? How did a tiny capitalist elite driven by the relentless, remorseless pursuit of profit get a death-grip on New York City? What does this history mean with regard to the Democrats today, and why we fight for a revolutionary workers party against them and all capitalist politicians? The dramatic story told by The Kidnapping Club helps us get to the roots of some these issues. The courageous example of abolitionists like David Ruggles, who organized to stop the abduction of black people here in New York City, are an inspiration as we struggle today to defend the rights of immigrants – against latter-day slave catchers and the racist deportation machine built up by Donald Trump’s Democratic predecessors and ruthlessly wielded by his administration today. ■

When

the White House Sent

Marines to Seize Fugitive Slaves

“The Runaway Slaves, Anthony Burns and THomas Sims, Returned to Slavery – Their March Through the Streets of Boston,” from The Story of My Life by Mary A. Livermore (1898).

Though New York’s Wall Street rulers hoped the infamous Compromise of 1850 would silence opponents of slavery, the most recent in the long series of bargains between the North and the slaveholding South proved to be explosive. The new Fugitive Slave Act that was a pillar of the compromise enraged abolitionists, as well as many Northerners who had sought until then to evade conflict over slavery. The act’s stipulation that slave catchers could force anyone and everyone to join the hunt for fugitives goaded the anti-slavery movement, and large numbers of people who had not taken action until then, towards a more militant stand. U.S. society was shaken by several high-profile clashes that erupted in Northern cities when people seeking to rescue fugitive slaves faced off against bounty hunters, who were backed up by the police and, in some cases, by federal troops.

The watershed moment came in 1851 when a group of fugitive slaves and free black people in Christiana, Pennsylvania successfully resisted a raid led by a federal marshal working together with a slave owner who sought their capture by force of arms. In response to the death of the slaveowner, President Millard Fillmore called out the Marines to carry out a manhunt, which led to the indictment of 38 black men and three whites on charges of “treason” (“for resistance in the execution of the Fugitive Slave Law of September 1850,” in the words of a widely circulated contemporary report on the trial). Meanwhile, the runaways escaped northward and found refuge in Rochester, New York, in the home of Frederick Douglass, who helped them reach Canada. Public outrage against the slave catchers led Douglass to proclaim that the Christiana Resistance had “inflicted fatal wounds on the fugitive slave bill.”

In May 1854, a mass upheaval broke out in Boston in response to a slave catcher’s kidnapping of Anthony Burns. Enslaved to a shopkeeper and sheriff in Alexandria, Virginia, Burns had learned to read and write, and found a way to escape by stowing away on a Massachusetts-bound ship. When Burns was seized (using the pretext of a false robbery charge) and scheduled for trial under the Fugitive Slave Act, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker and other militant abolitionists organized a mass meeting at Boston’s Feneuil Hall to plan for Burns’ rescue.

Some of the meeting’s participants tried to storm the building where Burns was being held, in order to free him. In response, President Franklin Pierce ordered a massive force of Marines, Army artillery units and state militiamen to take control of the city. (Pierce, a Democrat, had used his military career in the U.S. war on Mexico as a steppingstone to the White House.) As many as 2,000 armed men marched a shackled Burns through the city and to a waiting ship in Boston Harbor. A crowd of 50,000 gathered in protest, defying the bayonet lines and cannon placements.

Many Boston-area residents were radicalized by the case of Anthony Burns. Shortly after Burns’ abduction Theodore Parker, Henry Bowditch and other abolitionists formed a secret society called the Anti-Man-Hunting League devoted to aiding freedom seekers and resisting the slave catchers by any means necessary. In 1855, a group of black Bostonians purchased Burns’ freedom, and he subsequently attended Oberlin College. After Burns, no fugitive was ever taken back to slavery from Massachusetts.

In 1863, after Abraham Lincoln’s government finally yielded to insistent demands to establish a regiment of African Americans in the war against the slavocracy, the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment was enrolled (two of Frederick Douglass’ sons were among its recruits). As portrayed in the 1989 film Glory starring Denzel Washington, it played a heroic role in the Civil War that smashed chattel slavery – what Marxists call the Second American Revolution. ■

- 1. See “The Emancipation Proclamation: Promise and Betrayal,” The Internationalist No. 34, March-April 2013.

- 2. “The Hidden Links between Slavery and Wall Street,” BBC, 29 August 2019.

- 3. For some crucial context, see “Slavery and the Constitution: Origins of U.S. Capitalist ‘Democracy’,” Revolution No. 17, August 2020.

- 4. Becoming widely known in the 1830s, Garrison would go on to burn a copy of the Constitution on July 4, 1854, calling it “a covenant with death, an agreement with Hell.” (See “Slavery and the Constitution.”)

- 5. An in-depth account in the online history journal Commonplace (December 2024) gives further details, which differ in some ways from Wells’ account. The Brilliante case came three years before the rebellion of 53 African men held captive aboard the Spanish slaving ship La Amistad, which drifted to the coast of Long Island in 1839, leading to a famous legal battle the U.S. courts, events portrayed in the 1997 Steven Spielberg film Amistad.

- 6. Savannah, Georgia was later the site of what is believed to be the largest single sale of human beings in U.S. history, known as the “Weeping Time,” when in March 1859 approximately 436 enslaved people were auctioned off at a racetrack to pay off the gambling debts of a local plantation owner.

- 7. The Tombs, in downtown Manhattan a five-minute walk away from today’s immigration courthouses, continued operating until 2020, when it was demolished to make way for a huge new jail complex.

- 8. Nearly a century and a half later, the Journal of Commerce was purchased by the publishers of The Economist. It continues to be a mouthpiece of finance capital to this day.

- 9. See the Internationalist pamphlet Marx on Slavery and the U.S. Civil War (2009).